On Jan. 18, 2015, two Stanford graduate students found former Stanford swimmer Brock Allen Turner repeatedly thrusting himself upon an unconscious, semi-naked woman behind a frat house dumpster. Turner, who later dropped out of the university, attempted to flee but the men tackled him. In March, he was found guilty on three felony counts. The prosecution argued for six years out of a 14-year maximum in state prison, and the judge issued a clear statement against sexual assault at his sentencing: "Do not talk about the sad way your life was upturned because alcohol made you do bad things. Figure out how to take responsibility for your own conduct."

Actually, no. Those were the powerful words of the woman Turner raped, whose personal testimony went viral after the Guardian reported Turner's actual sentence last week: registering as a sex offender and serving six months in county jail with probation — three if he gets out early for good behavior. "A prison sentence would have a severe impact on him," said Judge Aaron Persky, explaining the decision. "I think he will not be a danger to others."

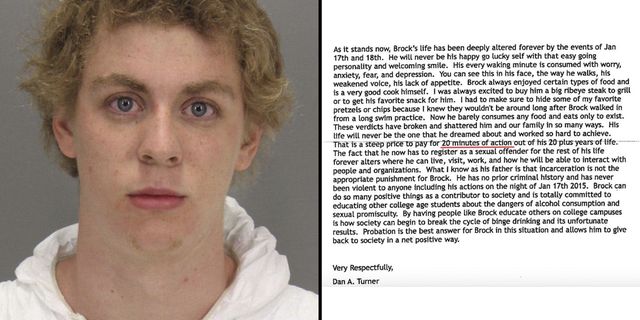

But on what basis is Persky making that assessment? Turner's statement in court does not suggest that he has realized the severity of, or assumed responsibility for, his crime. He pleaded not guilty to sexual assault, instead saying that the encounter was consensual and that, because they were both drunk, he didn't realize that the woman became unconscious. According to the victim's letter, he dismissed the incident as a symptom of drinking alcohol and pledged to "speak out against the college campus drinking culture and the sexual promiscuity that goes along with that." In the defense's sentencing memo, Turner's lawyer Mike Armstrong wrote , "He is fundamentally a good young man from a good family with a record of real accomplishment who made bad choices during his time at Stanford of about four months, especially related to alcohol." In a letter to the judge, Brock's father, Dan Turner, reportedly wrote that it would be unfair that "20 minutes of action" could lead to incarceration, especially since Brock has always been an upstanding member of his community. Stanford law professor Michele Dauber, who is also a friend of the victim's family and is among those who have signed a petition to remove Persky from the bench, shared an excerpt of Dan Turner's now-viral letter on Twitter:

The thing is, no one has a criminal record until they commit a crime, but that doesn't mean the crime isn't a crime. The rush to humanize Turner and grant him a lenient sentence is an example of a system that elevates the voices and experiences of white men, and dismisses violence against women. As a young, successful white male athlete, Turner benefits from a level of compassion and empathy rarely expressed for any other group of people in America, a benefit of the doubt that people of color and women rarely get. In fact, they are often subject to higher levels of scrutiny simply by virtue of not being white or male.

For black men and women, this is often a life-or-death matter: They are routinely shot down by white guys with guns who make snap judgments based on unfounded fear. According to a recent study for the Bureau of Justice Statistics, black defendants face longer sentences than white defendants for the same crimes — a problem that has worsened as judges have gained more power over sentencing terms. Though white people are more likely to deal drugs, black people are disproportionately arrested for it. The media often betrays the same bias, jumping at the chance to humanize white killers and suspects, while writing about black suspects more harshly. Many people of color in this country, especially from low-income backgrounds, don't get a first chance, let alone a second or a third.

Brian Banks, a black man and former football star who served five years in prison for wrongful rape conviction, believes that Turner benefitted from lots of hidden advantages. Like Turner, Banks had no prior criminal record when he was arrested at 16. But he was tried as an adult, spent a year in juvenile hall before his case was heard, and faced up to 41 years in prison. He took a plea deal rather than go to court because, the New York Daily News reports, "It was a better option, he was told, than a young black kid facing an all-white jury." "I would say it's a case of privilege," Banks told the Daily News, continuing:

It seems like the judge based his decision on lifestyle. He's lived such a good life and has never experienced anything serious in his life that would prepare him for prison. He was sheltered so much he wouldn't be able to survive prison. What about the kid who has nothing, he struggles to eat, struggles to get a fair education? What about the kid who has no choice who he is born to and has drug-addicted parents or a non-parent household? Where is the consideration for them when they commit a crime?

The 23-year-old victim raised the same issue in her letter: "If a first time offender from an underprivileged background was accused of three felonies and displayed no accountability for his actions other than drinking, what would his sentence be? The fact that Brock was an athlete at a private university should not be seen as an entitlement to leniency, but as an opportunity to send a message that sexual assault is against the law regardless of social class."

Turner's status as a white man also disassociates him from the severity of his crime. America has a long history of ignoring white men who rape, while liberally casting men of color as rapists. That image persists today — Donald Trump, for example, has characterized Mexicans as criminals and rapists, and in 2015, before South Carolina shooter Dylann Roof went on a murderous rampage at a black church, he wrote, "You rape our women, and you're taking over our country, and you have to go." According to Stanford historian Estelle Freedman's 2014 book Redefining Rape: Sexual Violence in the Era of Suffrage and Segregation, this stereotype that black and immigrant men are sexually aggressive took hold in the 19th century. It was mostly white men who determined who would pay for these crimes — they created the laws, sat on the juries, and overheard the cases as judges. Pacific Standard magazine explains that "Consequently, rape laws, as Freedman writes, actually 'contributed to the immunities enjoyed by white men who seduced, harassed, or assaulted women of any race,' and by doing so, reinforced their own 'sexual privileges.'"

Turner also inherently benefits from a hyper-masculine, sports-obsessed culture that devalues women and casts doubt on sexual assault victims, 91 percent of whom are female. Most rapes go unreported, and sexual assault convictions are rare. Those who come forward — especially against venerated figures and athletes — are shamed, silenced, stigmatized, and blamed. "The seriousness of rape has to be communicated clearly, we should not create a culture that suggests we learn that rape is wrong through trial and error," the victim wrote in her letter. "The consequences of sexual assault needs to be severe enough that people feel enough fear to exercise good judgment even if they are drunk, severe enough to be preventative." Instead, Dauber says, the judge did the opposite. "He has made women at Stanford and across California less safe," she told the Guardian of the sentence. "The judge bent over backwards in order to make an exception … and the message to women and students is 'you're on your own,' and the message to potential perpetrators is, 'I've got your back.'"

As Twitter user @absurdistwords wrote, rich white male privilege is the "ability to be convicted of rape and have the court basically apologize for the inconvenience." White male privilege is the ability to commit one of the most heinous crimes imaginable and yet walk away with a slap on the wrist. White male privilege is a judge having faith that a promising athlete will never rape someone again, despite the fact that the man took no responsibility for raping someone in the first place. White male privilege is raping a woman and getting empathy for how hard it must be for the rapist to carry on. The outcome of Turner's case demonstrates that in order to find justice for rape victims, we must also dismantle white male privilege.

Follow Prachi on Twitter.

Prachi Gupta is an award-winning journalist and former senior reporter at Jezebel. She won a Writers Guild Award for her investigative essay “Stories About My Brother.” Her work was featured in The Best American Magazine Writing 2021 and has appeared in The Atlantic, The Washington Post Magazine, Marie Claire, Salon, Elle, and elsewhere. PrachiGupta lives in New York City.