It’s never been a more exciting time to be a linguist working with Australian Indigenous languages – at least according to linguist Murray Garde.

When the languages of Australia’s first peoples are spoken in prominent public settings, it often makes national headlines. In February the prime minister, Malcolm Turnbull, spoke Ngunawal to deliver the Closing the Gap report (which showed little progress in reaching targets).

Turnbull’s speech came within days of the Northern Territory MLA Bess Price objecting to not being allowed to speak her first language of Warlpiri in parliament – even if it was just a throwaway retort to the opposition.

For many non-Indigenous Australians these were unique and interesting moments. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people they were too rare instances of hearing Indigenous languages used in mainstream Australia.

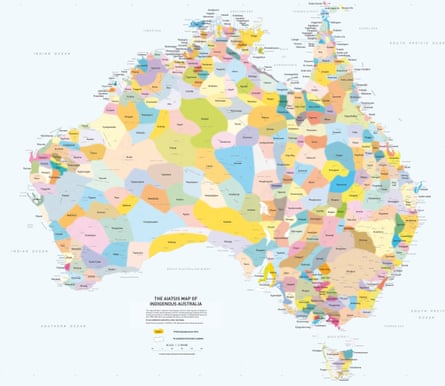

Less than half of the estimated 250 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages which have existed on this continent are still in some form of use. The vast majority are considered endangered.

“There are probably only 20, 30, 40 which are looking like they’ve got a good chance of survival across next generations,” Garde tells Guardian Australia.

“But we’re trying to address that,” he adds. Indeed in the past couple of decades non-Indigenous Australia have cottoned on to the importance of preserving and rescuing the languages of first nations people, and we are in the midst of a resurgence in appreciation, he says.

“There’s a whole range of reasons why we think it’s important Australia’s Indigenous languages are supported, maintained and revived,” says Garde.

Aside from historical or academic reasons, aside from the basic right of Indigenous peoples – enshrined in international agreements – to have their traditional language preserved, there are socially pragmatic reasons to keep these languages alive.

“The mental health of people in small remote communities is tied to the ability of those people to express themselves in first language,” says Garde.

“If their language is acknowledged or even used with interpreters [during their daily lives, employment or interactions with government services], those of us who have been working in this space for decades know that those communities function a lot better.”

Today across the country concerted efforts are under way to preserve and pass languages down to the next generation to ensure their survival.

Indigenous languages were introduced to the New South Wales curriculum as a higher school certificate subject this year, while schools in other states have begun offering some classes. Australian universities are increasingly offering tertiary courses.

Language centres offer grassroots classes and educational resources. City councils are embracing Indigenous place names.

The world of mobile apps and online research tools are making languages, their history and their context more accessible to non-Indigenous Australians who wish to better understand and interact with the oldest continuing culture in the world.

Last year Charles Darwin University launched a searchable online dictionary of Yolngu Matha – the languages spoken across much of Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory. Its success has prompted Garde to begin work on a similar project for Bininj Kunwok. A key concern, he says, is to make sure the language is controlled by the community to ensure they retain ownership over a significant part of their culture. The same concerns are held about language programs in mainstream education, outside the control of community groups and caretakers of traditional knowledge.

In March Canberra’s Australian National University launched the Austkin database of Indigenous kinship terms and skin names, which seeks to preserve those still heard every day in communities, as well as create a database of terms in languages which are essentially extinct except for mentions in historical archives.

There is a need among Indigenous groups to maintain the culture and heritage of a traditional language. The battle is fought on two fronts, says the lead investigator for the database, Dr Patrick McConvell: by those seeking to maintain their endangered languages, and by those trying to revive ones no longer used.

“When people try to recreate languages, they often will focus in on kinship terms as being an important thing to revive because it’s such a fundamental bedrock for their community,” McConvell tells Guardian Australia.

“People feel very much that language is the thing that can help them to bring back, not just their identity, but their ways of dealing with each other.

“We’re working with some people who have still got their language and kinship system but they fear that their children are losing it so they’re very much trying to save it.”

Many of the programs operating around the country focus on passing the knowledge down to the next generation. “Obviously it’s going to die out if the kids don’t learn it,” Dallas Walker says. “We’ll have done all this for nothing.”

Walker is a research consultant with the Muurrbay Aboriginal Language & Culture Co-operative on the New South Wales mid-north coast, which supports the revitalisation of languages from seven regional Aboriginal communities.

Teaching schoolchildren the local Indigenous languages is one of the key activities offered by the Nambucca centre, which was started by Gumbaynggirr elders in 1986. In 1997 they began teaching Gumbaynggirr and in 2004 expanded to cover six other regional languages.

“It used to be just Indigenous kids and now we’re open to all,” Walker says. “If one kid’s going to learn it, why not all? It’s good for everyone.”

Some of the children who learn Gumbaynggirr through the centre are “right into it” but others are more focused on learning swearwords, he says, laughing. “Our aim is to get them to start speaking it, they’re our next teachers.

“That’s our identity and culture, it keeps you on your toes and keeps you happy. Kids have got to know where they come from and have a sense of identity. If they don’t have that where do they end up?”

In 2008 the Northern Territory government effectively ended the practice of “two-way” education in Aboriginal community schools, decreeing that the first four hours of classes must be taught in English. Critics, with research to support them, said the move made it harder for children to learn and bilingual education was more effective for Indigenous students.

For people who are striving to revitalise language and support disadvantaged communities, that decision is among a number they consider to be backwards steps.

The 2014 second national Indigenous languages survey (2Nils) found successful delivery of language programs required involved and committed community members, access to language resources and adequate funding.

The first, ongoing national funding to preserve languages began in 1992, but the money has been inconsistent. In just the past three years federal funding has been increased, then cut by almost $10m, then boosted again. In December an extra $3m was earmarked for 59 language and arts activities.

The minister for communications, Mitch Fifield, defended the government’s record, telling Guardian Australia it had funded Indigenous language support since the 1970s and now provided about $20m a year.

“Today, the Australian government continues to support activities that record, revive and maintain Indigenous languages so that they can be safeguarded and passed on to future generations, preserving this important part of Australia’s cultural heritage,” he says.

The 2Nils, which examined the state of Indigenous language in Australia, found strong concern at the rate of loss, and said activities around the country were not just about restoring languages for the sake of it but also went to improve the wellbeing of Indigenous people.

Participants expressed a desire to see not just an increase in the proficiencies of speakers, but also “for the language to have a stronger presence in their own and wider communities, noting that this in turn strengthens identity and connection with country and heritage”.

In the NT, where about a third of the community ks Indigenous, a local ABC radio station has sought to do just that.

I heard it on the radio …

Late on a weekday afternoon in the Top End, listeners of ABC Darwin might catch an unusual news broadcast. For the past two years journalists and producers have worked with interpreters to put together daily bulletins in three Indigenous languages.

“This idea came up as one where we can reach the community, hear more Indigenous voices on the radio, and try and do this within our existing capacity,” says Rob Cross, the news director for ABC Northern Territory. Most Indigenous Territorians speak English as a second – or further – language.

“We prepare the bulletin, so our morning radio subs have had it added to their duties to pick some stories that may be of interest to the Indigenous community. We then send it to the Indigenous Interpreter Service. They decide if a story’s suitable or if there are any other stories they’ve heard they might like. They sort of rewrite it to how it might sound best in an Indigenous language.”

Bulletins in Warlpiri, Yolngu and Kriol are uploaded to a website where they can be heard and downloaded by listeners and remote Indigenous broadcast services for further transmission. A shortened version is broadcast each afternoon.

“People who want to listen to it and understand the language obviously go to the webpage,” says Cross. “But the little snippets or stories we play on local radio are a chance for people to go, oh that’s Warlpiri or that’s Yolngu and it just keeps the languages alive.”

Fighting fire with language

Elsewhere in the NT, a program has taken the connection between language and knowledge and applied it to a world-leading environmental program.

Ten years ago the West Arnhem Land fire abatement project turned to traditional fire management practices to protect the Arnhem Land plateau environment.

Over the decades many of the local people had moved away from the plateau – known as rock or stone country – and were no longer using traditional methods to manage fire. Large and uncontrollable bushfires were tearing through Arnhem Land and neighbouring Kakadu, causing devastation.

Traditional knowledge of fire management which related specifically to that corner of the earth was contained in the Bininj Kunwok language, says Garde.

“Their elders grew up living on the rock country, interacting with the environment which had a continuity with life for thousands of years,” he says.

“They had extensive knowledge about the environment, about plants and animals – how to refer to the landscape, the way the landscape is broken up – a kind of taxonomy of the land forms.”

Terms for the plateau’s landscapes, the different parts of a fire, even the patterns flames left in the land, all formed part of the detailed land management knowledge of the group.

The cultural knowledge was something which wasn’t appreciated until recent decades, says Garde. Now it’s incorporated into the fire management program by Warddeken rangers from Kabulwarnamyo, Mimal rangers from Bulman, Jawoyn rangers from Katherine and Adjumarllarl rangers.

“The last old professors as we called them, they’d explain to the younger rangers how to burn the country at a particular time of year in a particular ecological zone,” says Garde.

“These remnant rainforests on the plateau, Aboriginal people value them greatly as places of shade to camp in, so they had a particular way of burning it so as not to damage.

“We realised this was incredibly important for land management today, and it’s also providing employment with the ranger program … All the ranger programs are very keen on having a language component in their work.”

The growing range of individual programs is a positive step towards saving languages but a long-term strategy is needed, says Garde.

Across Indigenous communities languages are spoken in everyday life and are inextricably linked to traditional knowledge and culture.

“When you think about the scale of the issue … there’s always room for more if you realise these positive spinoffs from what language maintenance and revival can offer.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion