Exit a man with a talent to amuse

One night in the spring of 1959 I sat down to dine at Sardi's, the New York theatrical restaurant. Crowded before the Broadway curtains rise and after they fall, it is usually empty in between, and was on this occasion. Suddenly I looked up from the menu and froze. Noël Coward, also alone, had come in; and that very morning the New Yorker had printed a demolishing review by me of his latest show, an adaptation of Feydeau, called 'Look after Lulu'.

I knew him too well to ignore his presence, and not well enough to pass the whole thing off with a genial quip. No sooner had he taken his seat than he spotted me. He rose at once and came padding across the room to the table behind which I was cringing. With eyebrows quizzically arched and upper lip raised to unveil his teeth, he leaned towards me. 'Mr T,' he said crisply, 'you are a cunt. Come and have dinner with me.'

Limp with relief, I joined him, and for over an hour this generous man talked with vivacious concern about the perils of modishness. ('There's nothing more old-fashioned than being up to date'), the nature of the writer's ego ('I am bursting with pride, which is why I have absolutely no vanity'), the state of the theatre in general and of my career in particular. Not once did he mention my notice or the play. It would have been easy to cut or to crush me. It was typical of Coward that he chose, with an almost certain flop on his hands, to amuse and advise me instead.

As a writer, this was one of his bad times, and there had been many since the war – since indeed, the high period from 1925 to 1941, which produced the five plays by which he will be remembered. 'Hay Fever', 'Private Lives', 'Design for Living', 'Blithe Spirit' and 'Present Laughter'. 'Sign No More', the revue he wrote in 1945 to celebrate the return of peace, was an especially low point, although it contained some marvellous things: the title song, for example, at once joyful and elegiac, and 'Nina from Argentina', a model of intricate rhyming on which Cole Porter at his best could hardly have improved.

Lowest of all was 'Pacific 1860', Coward's Drury Lane musical of 1946, of which I remember little except Graham Payn singing about his awestruck affection for a South Sea volcano by the name of Fum-Fum-Bolo. But even if we agree that Coward the postwar writer was past his prime, it's impossible to accept the judgment laid down by Cyril Connolly in 1937:-

One can't read any of Noël Coward's plays now. They are written in the most topical and perishable way imaginable, the cream in them turns sour overnight.

In fact his best work has not dated, by which I mean his most devotedly ephemeral. One feels the same about many movies of the 1930s: with the passage of time, the profundities peel away and only the basic trivialities remain to enchant us. They have certainly enchanted John Osborne, who learned from Coward the disparaging use of 'little' (as in 'nasty little', 'repulsive little', 'disgusting little' etc), and Harold Pinter, whose spare allusive dialogue owes a great deal to Coward's sense of verbal tact…

I first met Coward in the early 1950s, during his cabaret seasons at the Café de Paris, and heard him exploding with mock-outrage when he found in 1954 that the place had been completely redecorated in honour of Marlene Dietrich's impending debut. 'For Marlene,' he said, 'it's cloth of gold on the walls and purple marmosets swinging from the chandeliers. But for me – sweet f– all!'

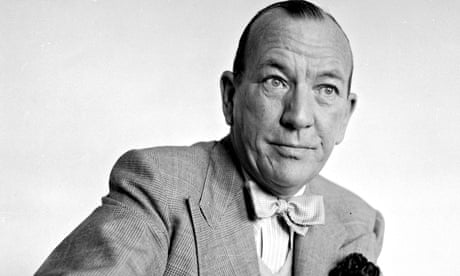

To describe his own cabaret appearances, I went back to his boyhood and wrote: 'In 1913 he was Slightly in "Peter Pan", and you might say that he has been wholly in "Peter Pan" ever since.' The young blade of the 1920s had matured into an old rip, but he was as brisk and energetic as ever: and if his face suggested an old boot, it was unquestionably hand-made. The qualities that stood out were precision of timing and economy of gesture – in a phrase, high-definition performance. After a lifetime of concentration, he gave us relaxed, fastidious ease.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion