EastEnders

Over the years, EastEnders has been guilty of all sorts. It has traditionally only ever allowed one black and one Asian family into Albert Square at a time. There was its portrayal of cot death, which turned a normal mother into a frothing, baby-switching maniac. And its weird insistence on reviving dead characters such as Den and Kathy seems to condone a form of witch-doctory that flies in the face of conventional modern medical knowledge.

The most problematic aspect of EastEnders however, is its portrayal of the working class. In short, they’re still on EastEnders. It’s like nobody who makes EastEnders has actually been to East London for the last decade. Where are the oligarchs? Where are the simultaneously cramped and extortionate flat shares? Why hasn’t Dot Branning been gentrified out of London to Gillingham? Why aren’t there three or four branches of Pret constantly within everyone’s eyeline? Everyone in EastEnders is poor and miserable, even though they all own million-pound houses, and this is nothing less than shameful. SH

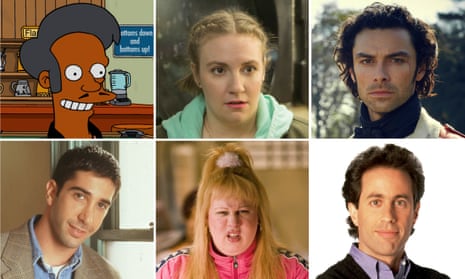

Girls

Let me start by saying that Girls was – and will always be – a very important piece of television, which paved the way for the likes of Master of None, Broad City and Fleabag. However, it was also deeply flawed in many ways, the most important of which was its claim at universality. Girls is a title that promises a shared experience, and instead hones in on a white, largely straight, very privileged set who, for all their serious issues – their depression, OCD and abortions – are largely affected by first world problems of the highest order. From the very first episode, where Hannah Horvath declares herself the voice of her generation before settling on “a generation”, the message is clear: this is Woody Allen-style introspection, just with far less self-awareness.

Then there is the question of race. “I had been thinking so much about sort of representing weirdo girls and chubby girls and strange half-Jews that I had forgotten that there was an entire world of women who were being underserved,” Dunham told the Hollywood Reporter in 2015, admitting that Girls had fallen well below the mark where representing the world around it was concerned.

Yes, there was Donald Glover’s brief turn as Sandy – almost a meta-commentary on Girls’ lack of diversity – and yes, there was Riz Ahmed, who dropped into the final season during Hannah’s dreamlike trip out of town. The key cast of Girls, however, was homogeneously white in a way that, by season six, felt out of step with the growing intersectionality of TV, and feminism. Half the pleasure of Issa Rae’s Insecure or Aziz Ansari’s Master Of None is watching underrepresented narratives unfold – in the world of Girls there just didn’t seem to be space, or a willingness to create any. HJD

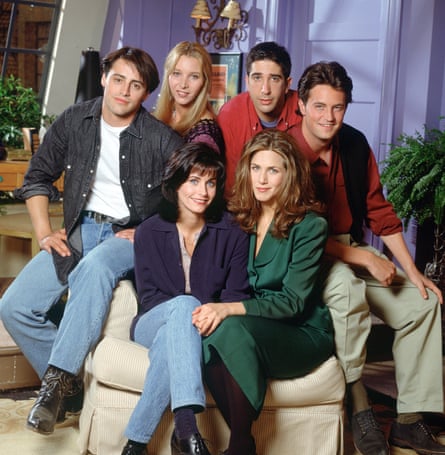

Friends

You’d think that the most mainstream comedy of all time might be bogged down in regressive politics, but Friends didn’t spend its 10-year run locked in a perpetual navel gaze. It broke with tradition thanks to storylines featuring a long-running lesbian relationship (including the first ever lesbian wedding on a scripted show), a transgender character and plots about surrogacy and adoption. There was also an undeniable sense of gender parity among the Central Perk six.

Nobody could argue, however, that Friends was a bastion of diversity – the whole thing was whitewashed enough for Michael Moore to chillingly comment that he liked that there are no black friends on Friends, “because in real life friends like that don’t have black friends.”

Ironically, the most progressive stories prompt the most offensive material: Carol, Ross’s ex-wife who left him for a woman, is the starting point for umpteen jokes about lesbians and the challenge they pose to male authority (the men also fetishise the idea of “girl-on-girl action” with regards to their female friends in a way that contributes a rare strand of sexism to the show). Most notoriously, there is the case of Chandler’s father, the star of a Las Vegas drag show who is played by a woman, and who is treated with a fierce repulsion by Chandler and as punchline-fodder for everyone else. There is also endless banter about Chandler appearing gay, something that is initially fuelled by his own angst and later simply thrown at him as an accusation by the other characters.

The worst thing about the homophobia in Friends, however, is not the homophobia in Friends. Instead, it’s the reminder of how uncontroversial it has been to casually, and slipperily, demean LGBTQ people. Friends co-creator David Crane is gay, and has been quoted as saying he didn’t think Chandler “was homophobic in the least”. A decade of identity politics later and it’s increasingly difficult to see his point. RA

The Simpsons

First things first: The Simpsons – or at least its imperial, season-four-to-nine period – is one of the greatest TV shows of all time. It is a dizzyingly brilliant pop-culture collage that reshaped the way we think about art, commerce, family and where best to buy a hammock. But, alas, as cromulent as it otherwise is, The Simpsons has one inescapably problematic element: its resident Squishee-distributing Kwik-e-Mart vendor, Apu Nahasapeemapetilon.

It almost seems bizarre how long we’ve collectively turned a blind eye to Apu, given that he’s a pretty flimsy Indian-American stereotype performed, Peter Sellers-style, by a white person (Hank Azaria). Americans of Indian or south Asian descent have long contended that Apu is little more than a racist caricature – an entire complex, multi-stranded culture boiled down to a silly voice. Even worse, at a time when actual Indian-Americans were scarcely seen or heard from on TV or in film, that silly voice became the default depiction. Witness the excruciating ‘do the accent’ audition scenes endured by Dev in Master of None, or the excruciating ‘do the accent’ audition scenes endured by Kal Penn in real life.

The counter-argument goes that Apu is in fact a subversive parody of an offensive parody, a commentary on lazy stereotypes. This is fine in theory, but less so in a reality when the deck is so firmly stacked against one group. “The Simpsons stereotypes all races. The problem is, we didn’t have any other representation,” says Mindy Project actor Utkarsh Ambudkar in The Problem With Apu, a new documentary on the character from comedian Hari Kondabolu. In an interview with the Huffington Post, Kondabolu argued that Apu is “an example of a character who would never have been written if the show started today.” It’s hard to disagree. GM

Sherlock

Much has been made of Sherlock co-creator Steven Moffat’s difficulty with female characters – there are countless Tumblrs devoted to his perceived deficiencies – but it’s wrong to claim that he hasn’t tried to counter these. In fact, you could argue that he’s actually tried a little too hard. In the odd little Victorian-era outlier episode The Abominable Bride, it seemed clear that Moffat wanted to demonstrate his working knowledge of feminism.

He did this by reimagining the Suffragettes as a sort of spooky murder cult – quite a panicky way of viewing women in itself. He then topped it by making Sherlock describe the movement as “the invisible army hovering at our elbow, tending to our homes, raising our children, ignored, patronised, disregarded, not allowed so much as a vote”. He made Sherlock say this in a roomful of women. Steven Moffat literally made Sherlock mansplain feminism to the actual Suffragettes.

The counterargument is that it was simply a fever dream that took place inside Sherlock’s mind, and demonstrated a sort of internal epiphany for a character known for his regressive views on women. Whatever the intention, the execution was lumpen. SH

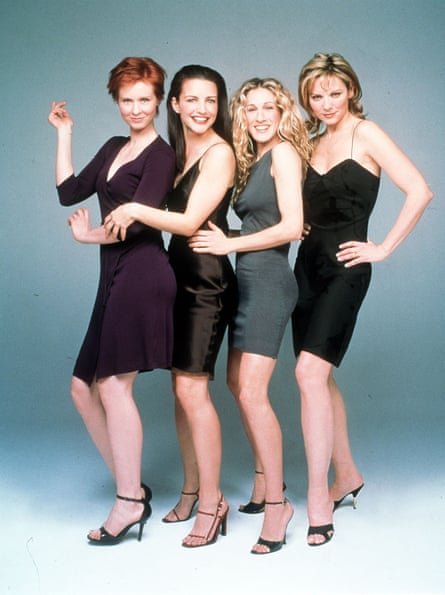

Sex and the City

At the risk of sounding like Samantha, queen of sass herself, Sex and the City has more problematic strands than Carrie has Jimmy Choos.

Although the charm of this show is in its kooky fashion, excessive pun work, aspirational fruit salad brunches and afternoon Manhattans, there are numerous issues that crop up, puncturing its decadent veneer. For example, the fact that Carrie – a professional sex columnist – claims bisexuality is but a “layover on the way to Gaytown”. Or the extraordinary whitewashing of New York City. When actors of colour do arrive they are flung into roles which are excruciatingly basic, evil or an exhausted stereotype. Take Sum, the scheming yet loyal servant of Samantha’s wealthy lover Harvey in season 2, or music exec Chivon, Samantha’s date in season 3, and his sister Adeena –who play the reductive roles of well-endowed sex object and angry black women. (There is also some brazen racism in the film Sex in the City 2 - Hadley Freeman said: “All Middle Eastern men are shot in a sparkly light with jingly-jangly music just in case you didn’t get that these dusky people are exotic and different.”)

Other areas of distaste involve the treatment of class, lesbianism, religion and, to some extent, feminism itself. Carrie ends up with the debonair and manipulative Mr Big, largely because he promises her a walk-in wardrobe. Witty and intelligent Miranda, the high flying lawyer, is frequently the butt of the joke (she is also the only member of the gang who eats carbohydrates, it pains me to admit I have noticed). Samantha’s chandelier smashing orgasms are the stuff of young women’s nightmares (perhaps as a response to this bombastic portrayal of intercourse we are seeing a generation of female writers like Lena Dunham and Phoebe Waller-Bridge write about sex in its most fumbling and ugliest form). Its creators are probably more fearful of the Bechdel test than Samantha was her STI swab. To conclude, Sex and the City: fabulous for inspiring sass, but not so good for society. HG

Little Britain

Even at the peak of its popularity, Matt Lucas and David Walliams’s Little Britain was a PC-baiting nightmare. Especially uncomfortable in its portrayals of disability, it featured characters such as Andy, who pretends to need a wheelchair due to laziness, and Anne, a truly outrageous creation that exists purely to mock those with severe learning difficulties. Yet it is West Country teen Vicky Pollard that makes Little Britain a textbook example of problematic TV. Pollard was a perfect storm of conservative anxieties: she was working class, she was overweight, she was a single mother (of 12 children), she was a criminal. At one point she swapped her child for a Westlife CD.

“People always say ‘oh I know a Vicky Pollard’ and I think that’s when you have a kind of real cultural moment”, said Walliams on the South Bank Show in 2005. The “cultural moment” she actually heralded was presumably not the one Walliams was thinking of. Soon, Pollard had become the poster girl for the demonisation of the working classes. She was a character on to which people could project their hatred of poor women, such as journalist James Delingpole, who said Pollard represented “gym-slip mums who choose to get pregnant as a career option; pasty-faced, lard-gutted slappers who’ll drop their knickers in the blink of an eye.”

Yet Pollard and her real life peers weren’t just a punchbag for the press. By the turn of the decade, hostility towards low-income people was so overwhelming that the Tories ran a poster saying “Let’s cut benefits for those who refuse work” to help them win votes. Austerity then ended up disproportionately punishing single parents, 86% of whom are women. There’s no yeah-but-no about it, Pollard helped fuel the mood that got the UK to that point. Little Britain remains a thoroughly questionable chapter in British comedy because of it. RA

Poldark

There’s one especially tricky moment in the Poldark novels. It’s when Ross angrily confronts Elizabeth, kisses her against her will then carries her to the bedroom while she screams for him to stop. This is where the scene ends. It sounds a lot like rape, but the book isn’t explicit about it. The 1970s BBC series is more forthright about what happens – Poldark holds Elizabeth down on the bed while she screams at him – although not in a particularly graphic way, thanks to the programme’s early evening time-slot.

In the modern version the scene plays out as originally intended, right up until Elizabeth is on the bed, at which point she gives in to Poldark. It’s the slightest shade down from the scene in Straw Dogs – the one where it’s heavily implied that Susan George is actively enjoying her rape – and it makes for both uncomfortable viewing and irresponsible television. Prior to the series, it was reported that the cast and crew wanted “rape” to be downgraded to “consensual affair” – but the scene was shot with enough ambiguity to make the whole thing troubling. SH

The West Wing

Writer Aaron Sorkin might have wrought instant magic in the pilot with the most unsuspecting props – a crossword, a treadmill, an actual hoovering Hoover – but zoom out and the cracks start to show. Why is it that for all his formidable mastery at crafting complex male characters and unflappable dialogue for them, his female leads are so often loopy and shrill?

Where Sorkin employs otherwise serious men to strut their stuff (literally beating their puffed-up chests, collectively chanting “we da men!”) as a comedic device, the women are often employed as comedic devices themselves. Entire storylines come infused with an infantilising attitude towards its female characters – at one point a grown woman is told she’s a good girl; a silent-footed press secretary is told she should wear a bell around her neck; a lame guy “cries like a girl”; bad writing reads as if it was “written by a girl”. It’s this last one that grates the most. The irony being that the Gilmore Girls – so highly rated for its rapid fire dialog – was once (incorrectly) rumoured to have been written by Sorkin, rather than Amy Sherman-Palladino. DBS

Seinfeld

In 2015 Jerry Seinfeld told late night chat show host Seth Myers: “I could imagine a time where people say, ‘Well, that’s offensive to suggest that a gay person moves their hands in a flourishing motion and you now need to apologize’. I mean, there’s a creepy PC thing out there that really bothers me.”

On the surface it’s just a comment typical of a white, straight male of a certain age. Once you know who said it, however, you can also determine both the sparkle and the flaw of Seinfeld’s 90s sitcom. On the one hand Jerry has zoned in on a fertile topic for humour – the idea that remarking on something as simple as the motion of a hand could result in opprobrious censure. On the other he’s just lumped a whole group of people into a single bracket.

The Cigar Store Indian, The Chinese Woman, The Outing. Each are classic Seinfeld episodes which find humour in exploring the thoughtless prejudices of white males. While they challenge the individual prejudices – that homosexuality is unnatural, that having a passion for Chinese girls might be racist – they leave unchallenged the problems underneath (namely that white men get to identify and classify what is problematic, and in their own time too).

In my opinion, these contradictions exist because Seinfeld is very much a product of its time – so far politically correct, but no farther. I also like to believe that were the young Jerry (and especially the young Larry) at work today, they would both accept progressive social norms and at the same time mine humour from them. PM

What hit TV show have you found problematic in the past? Tell us why below.