Robin Dunbar: ‘He gave us a picture of who we really are’

Professor of evolutionary psychology at the University of Oxford

We were all gearing up for the summer of love when, in 1967, Desmond Morris’s The Naked Ape took us by storm. Its pitch was that humans really were just apes, and much of our behaviour could be understood in terms of animal behaviour and its evolution. Yes, we were naked and bipedal, but beneath the veneer of culture lurked an ancestral avatar. With his zoologist’s training (he had had a distinguished career studying the behaviour of fishes and birds at Oxford University as part of the leading international group in this field), he gave us a picture of who we really are. In the laid-back, blue-smoke atmosphere of the hippy era, the book struck a chord with the wider public – if for no other reason than that, in the decade of free love, it asserted that humans had the largest penis for body size of all the primates.

The early 1960s had seen the first field studies of monkeys and apes, and a corresponding interest in human evolution and the biology of contemporary hunter-gatherers. Morris latched on to the fact that the sexual division of labour (the men away hunting, the women at home gathering) necessitated some mechanism to ensure the sexual loyalty of one’s mate – this was the era of free love, after all. He suggested that becoming naked and developing new erogenous zones (notably, ear lobes and breasts), not to mention face-to-face copulation (all but unknown among animals), helped to maintain the couple’s loyalty to each other.

Morris’s central claim, that much of our behaviour can be understood in the context of animal behaviour, has surely stood the test of time, even if some of the details haven’t. Our hairlessness (at around 2m years ago) long predates the rise of pair bonds (a mere 200,000 years ago). It owes its origins to the capacity to sweat copiously (another uniquely human trait) in order to allow us to travel longer distances across sunny savannahs. But he is probably still right that those bits of human behaviour that enhance sexual experience function to promote pair bonds – even if pair bonds are not lifelong in the way that many then assumed. Humans are unusual in the attention they pay to other people’s eyes – for almost all other animals, staring is a threat (as, of course, it can also be for us under certain circumstances).

I can’t honestly say if the book influenced my decision to study the behaviour of wild monkeys and, later, human ethology. Having been immersed in the same ethological tradition out of which Morris had come, viewing humans this way was no controversial claim. Older zoologists, however, were a great deal more sceptical, often viewing the book as facile. What it might well have done for me was to create an environment in which the funding agencies were more willing to fund the kinds of fieldwork on animals and humans that I later did.

Angela Saini: ‘His arrogance has done untold damage’

Science journalist, broadcaster and author

From the moment The Naked Ape was published, female scientists and feminists rolled their eyes. For good reason. Desmond Morris credited hunting by males (and only males) as the one thing that drove up human intelligence and social cooperation. In a 1976 paper, American anthropologists Adrienne Zihlman and Nancy Tanner laughed at his implication that females had “little or no part in the evolutionary saga except to bear the next generation of hunters”.

His problem with women ran through every chapter. Let’s start with what females were doing while males were evolving. Morris answered: “The females found themselves almost perpetually confined to the home base.” But by his own admission, hunters would sometimes be away for weeks at a time chasing a kill. So how exactly were the womenfolk managing to feed their families in the interim?

His deliberate choice to ignore hunter-gatherers – the only people on Earth who live anything like the way our distant ancestors might have – blinded him to the fact that women are rarely housebound. We know, for example, that women gathering plants, roots and tubers and killing small animals tend to bring back more reliable calories than men do. What’s more, in many hunter-gather communities, including the Nanadukan Agta of the Philippines and the aboriginal Martu of Western Australia, women hunt. Martu women do it for sport.

What about the rest of us, who no longer hunt and gather, but live in towns and cities? “Work has replaced hunting… It is a predominantly male pursuit,” he wrote. Oh, Desmond, seriously? Anthropologists are fairly unanimous that in our distant past, men and women shared almost all work, including sourcing food and setting up shelter. That’s the harsh reality of subsistence living. Throughout history, there have always been working women.

His consistent failure to understand the impact of patriarchy and female repression bordered on the bizarre. He claimed that humans developed the loving pair bond to assure males their partners wouldn’t stray while they were off hunting. Females evolved to be faithful. But a few pages later he mentioned chastity belts and female genital mutilation as means of forcibly keeping women virginal.

“A case has been recorded of a male boring holes in his mate’s labia and then padlocking her genitals after each copulation,” he wrote, with the pathological detachment of a scientist observing flies in a jar. He never asked himself the obvious question: If women evolved to be faithful to one man, why did men resort to such brutal measures?

On other points of fact, time has simply proven him wrong. “Clearly, the naked ape is the sexiest primate alive,” he stated. Nope. That honour goes to the bonobo. Which incidentally happens to be a female-dominated species.

For 50 years, Morris’s arrogance (large chunks of his slim list of references were to his own work) has done untold damage to people’s understanding of our evolutionary past. We might forgive him for being a man of his time. But as a scientist, for choosing to overlook evidence right in front of his eyes, The Naked Ape still deserves as little respect as he showed half the human species.

Angela Saini’s latest book, Inferior: How Science Got Women Wrong and the New Research That’s Rewriting the Story, is published by Fourth Estate

Ben Garrod: ‘He made me stop dead in my tracks’

Broadcaster, primatologist and teaching fellow at Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge

Like many zoologists, biologists and naturalists before me, I was drawn to the thrill of exploration and tracking animals. But as a 12-year-old living in a seaside town in Norfolk, there wasn’t much to explore and limited species to stalk. Instead, my quarry was old books about nature, anthropology and evolution, and my territory was the dusty shelves of old bookshops. I still vividly remember chancing upon a slim volume one winter weekend. I slid the book from the shelf, mainly prompted by the title. I was fascinated by apes, and the word “naked” had a definite (if slightly intangible) appeal to my 12-year-old self.

I don’t think I’ve ever read a book quite so slowly. Partly because I needed a copy of the Oxford English Dictionary to help me comprehend each paragraph. I didn’t want to miss a beat in what became an intoxicating series of revelations about not only my species but apparently about me, too. I’d never experienced a book that reached out to the reader in such a way and even now, this still holds true for The Naked Ape in that you can’t help but examine where (or even if) you fit in with Morris’s observations.

I brushed over the sections covering the evolutionary achievements of the penis, the covert mission of breasts and the untold benefits of being naked, but stopped dead in my tracks when I read how, despite our few millennia as a species relishing in the glow of civilisation, our long lineage from our great ape precursors and hominid ancestors had left its indelible mark not only on our anatomy but upon our behaviour, also.

This idea that we are simply the by-product of millions of years of evolutionary tinkering and are not alone as the pinnacle of some benevolent creation was such a revelation that when the book was released it shocked many. Yes, this had been written before but never quite so eloquently and never in a way that was aimed at a non-expert audience. At long last, they were being invited to share in some of the biggest, best-kept secrets of our somewhat extended family.

As a scientist, there’s a lot more I could say… of course, some of its ideas are now dated and wrong but it was 50 years ago and science does move inexorably onwards. The thing about reading The Naked Ape is that it can do one of two things. It can either set light to the kindling of an inquiring mind, or – if it causes your eye to twitch in consternation at, for example, outdated views on the sexes – make you take stock of what you actually know. It sends you on an academic exercise, sieving through persuasive argument in order to pick out the tantalising glimmer of empirical evidence. I’ve gone from one to the other. I fondly still have my copy tucked between a book on baboons and a treatise on skeletal pathology.

The Naked Ape is like an old friend I’ve grown up with, realised that they’re not quite as perfect as I once thought – but have decided that they’re still cool enough to hang out with anyway.

Adam Rutherford: ‘Did anyone take this seriously in the 60s?’

Author and presenter of Radio 4’s Inside Science

I spent rather too much time in the last couple of weeks arguing with men about breasts. I forget how it began, but there was a phenomenal volume of Twitter correspondence asserting one of two statements as scientific fact: the first was that the permanently visible breasts in female humans (compared to all other apes, whose breasts only enlarge during lactation or estrus) are signals to attract males. The second was that the primary function of breasts is to attract males.

The latter seems trivial to dispel: a baby that starves to death is a greater evolutionary pressure than whether an adult male is turned on – breasts exist to feed babies. The first argument is trickier to contest. In nature, there are wondrous variants of what we call “secondary sexual traits” – those bodily parts or behaviours evolved to aid mate choice – the peacock’s tail, the bowerbird’s bower, lekking stags. For humans, it might seem obvious that breasts fall into that category, and in my online debates, in all cases, the evidence presented found its evolutionary origins in The Naked Ape: “The enlarged female breasts are usually thought of primarily as maternal rather than sexual developments, but there seems to be little evidence for this.”

The question of why we are different to other apes is valid. Aside from the definitional function of mammary glands in mammals, the reasons for our morphological differences are certainly worthy of study. Morris goes on: “The answer stands out as clearly as the female bosom itself. The protuberant, hemispherical breasts of the female must surely be copies of the fleshy buttocks, and the sharply defined red lips around the mouth must be copies of the red labia.”

Did anyone take this seriously in the 1960s? To me, this is little more than salacious guesswork, erotic fantasy science. And this is the fundamental problem with The Naked Ape: it is a book full of exciting ideas that have little scientific validity. The attractiveness of an idea in science has no bearing on its veracity. Sometimes they are presented as “common sense” arguments – it’s obvious, innit? But common sense is the opposite of science – our senses deceive us all the time, our profoundly limited experience skewers us with bias. In the case of the attractiveness function of breasts, this idea is almost entirely untested. The data simply does not exist. Maybe visible breasts are a secondary sexual trait in humans. It would be unusual, as in nature most of these types of traits are on males, and not all cultures regard breasts as erotic. Did boobs replace bums as a sexual signal when we became upright? I don’t know, but the point is that no one does. We could test this today with genetics, by establishing genes involved in breast development and searching the genome for the signatures of selection. But this has not been done.

In my experience, much of the academic field that The Naked Ape is emblematic of – evolutionary psychology – falls victim to similar scientific crimes. We call it “adaptationism”, or “panglossianism”, after Dr Pangloss from Voltaire’s Candide. An eternal optimist, he suggested there was a reason for everything, and everything had a reason. Hence our noses had evolved to balance spectacles on; we have two legs because that suits the dimensions of a tailored trouser. For Morris, and millions of men on the internet, breasts are attractive, therefore their purpose is to attract.

There is plenty to like about this book. Its descriptions of the physiology on show during various human activities are accurate, detailed and genial. To position us as animals and under the auspices of natural selection is happily Darwinian. The Naked Ape was colossally successful – 20m copies have been sold, which is an astonishing number for a book ostensibly about human evolution. Supporters have argued that its real value is in popularising science. The problem is, and has always been, that it is not science. It is a book of just so stories.

Adam Rutherford’s latest book, A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived, is published by Weidenfeld & Nicholson

Desmond Morris: life and work

1928

Born in the village of Purton, near Swindon.

1941

Attends boarding school in Wiltshire. Growing up during the second world war, he later claims that he pursued surrealism and zoology as a retreat from the human race. He tells the Bookseller in 2013: “If you are at all sensitive as a child and you see adults killing one another – and not in a criminal way, but an accepted way – that is a strange learning process. I thought, ‘This is the species I belong to?’”

1948

Following national service, enrols as an undergraduate in zoology at Birmingham university.

1950

Exhibits his surrealist art work with Joan Miró in London.

1954

Publishes his doctoral thesis, entitled The Reproductive Behaviour of the Ten-Spined Stickleback.

1956

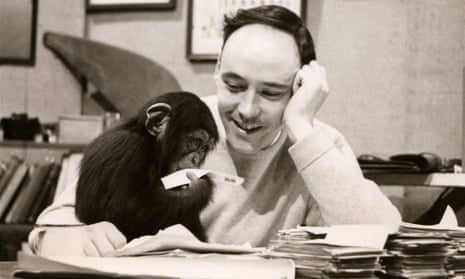

Is appointed head of the Granada TV and film unit at the Zoological Society, making programmes including Zoo Time for ITV; David Attenborough presented the rival show Zoo Quest for the BBC. Presents approximately 500 episodes of the show.

1957

Organises a exhibition called Paintings by Chimpanzees at the Institute of Contemporary Arts.

1959

Becomes the Zoological Society’s curator of mammals.

1966

Writes The Naked Ape over four weeks. “People think I deliberately wrote it to make a shocking bestseller, but it wasn’t like that,” he tells the Guardian in 2007.

1967

Appointed director of the ICA, where he encountered figures such as Henry Moore, Francis Bacon, Salvador DalÍ, Pablo Picasso and Barbara Hepworth. Supervises the institute’s move to the Mall. The first edition of The Naked Ape is published on 12 October and is serialised in the Daily Mirror.

1968

Following the success of The Naked Ape, he leaves his ICA post and moves to Malta with his wife.

1973

Returns to the UK to take up a research fellowship at Wolfson College, Oxford.

1977

Publishes his book Manwatching, which developed the concept of “body language”. It is one of more than 40 books Morris has written, including The Human Zoo, Intimate Behaviour, Babywatching, Dogwatching and Christmas Watching.

1978

Is elected vice-chairman of Oxford United football club.

1986

Begins work on The Animals Roadshow, co-presented with Sarah Kennedy.

2016

An updated edition of his 1981 book, The Soccer Tribe, is published with a foreword by José Mourinho.

2017

The BBC makes a documentary about his artistic career entitled The Secret Surrealist. The Express describes his artwork as “very obviously zoological… full of fantastical life forms resembling cells and gene maps and creatures of the deep, yet also possessing the friendly charm of The Clangers”.

Ian Tucker

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion