There’s a curse on your father’s books,” warned my daughter. They certainly began by causing trouble, right from the moment in the 1930s when the carpenter started installing the bookshelves. Hearing cries for help, my parents dashed into the front room to discover the poor man had somehow trapped himself between the wall and the wood. They released him, but now it is the books themselves that have trapped me.

As with many possessions drifting down the generations, whoever inherits them multiplies their actual value by the memories they trigger. As I have recently moved house and no longer have space for them, those memories are writ large at the moment.

Nearly 20 years after his death, I have fond, vivid and occasionally exasperated memories of Arthur Sale, my father, a fellow of Magdalene College and a man who “had read everything twice”, according to Bamber Gascoigne, an ex-student.

Arthur was always up for an intriguing chat about life, odd relatives and bizarre colleagues. Literature, too: he held that King Lear, the only really successful tragedy, was spoiled by being put on stage. There was no point in reading Tolkien when you could turn to the original Nordic myths, to which my retort was: “You have to walk before you can rune.”

He was sometimes, like the poetry he wrote, “wilfully obscure” (as a publisher friend put it). We hardly talked about my mother after her death and when he rang to say he was marrying again, his words were so oblique that I had no idea what he was on about.

He had strong opinions – he was a pacifist, as I am – but cautious about expressing them. He was generally gentle, but could be very sharp. He was highly impressed that I made a living out of journalism.

He was more hands-on than most fathers of his generation, although this consisted more of reading Great Expectations to me than sharing the duty of nappies or bathtimes.

I do not need his books to remember him. For a start, on the day Arthur died, my stepmother pressed on me his Parker fountain pen, an enormous trunk, a smaller trunk that my mother believed to have once belonged to EM Forster, and my father’s desk, at which, it now occurs to me, he never actually sat, as it is slightly too small for adults (I used to do my homework at it). The desk is still too small for an adult, but I welcomed it into my own house and, now that I have moved in with my partner, it has come with me.

Moving house brings the problem of inherited artefacts to centre stage and there is a limit to how much my stuff can push out my partner’s stuff. My father’s books are well over that limit. They were part of my childhood: many titles may have changed over the years, but it was like a river of books; individual volumes, such as the early Dickens novels, may have flowed on, but the riverbanks, or shelves, remain.

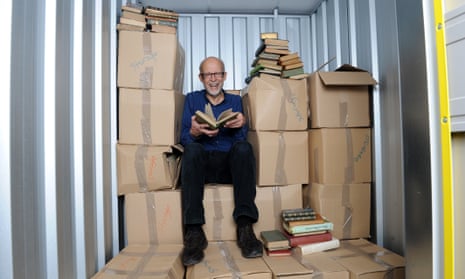

After his death, I ended up with most of the collection shoehorned into my house, an entire wall. The volume of the volumes amazes me. One thousand books. At an average of, say, 100,000 words each, that’s 100 million words, printed, in the case of a battered copy of Ben Jonson’s plays, nearly half a millennium ago. A lengthy shelf life.

Here are the classics you would expect, such as George Eliot’s Middlemarch, which comes in the shape of a tatty, four-volume 1871 edition. The spine had fallen off the first volume and Arthur glued it back – upside down, which may not have increased its value. His copy of DH Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers was an early edition that I read as a teenager; it must now be worth less, as he corrected a few misprints, however neatly, in pencil.

Then there were the obscure publications: a beautifully bound set of unreadable 18th-century sermons and now-forgotten novels. Few homes will have, as his did, the unfortunately entitled Sacred Poems and Pious Ejaculations by Henry Vaughan. Some books had not been read once, let alone twice, as their pages were “uncut”; they had not been correctly sliced after printing and my father had left them in their virgin state.

It is a fascinating and evocative collection of books. It is now in storage and I am trying to give it away. My ambition is that the collection should be kept together for researchers, which in a small way would carry on Arthur’s teaching. Sadly, there are so far no takers.

The books represent the inheritance dilemma writ large. In my own student life, all my worldly belongings fitted into the back of a taxi. Downsizing this summer, I realised I was lumbered with lumber large and small. What happened to the chuck-it-away society? We are the hang-on-to-it-for-the-children society. At least, I am; after we had scattered my wife’s ashes, I kept for years the plastic container that had housed them.

Arthur never gave shelf room to a slim volume of his own carefully crafted letters, published by his college, but that was because he was dead before it came out. When this memorial work was being compiled, I was rather hurt that, while he had found time to send his elaborate epistles to everyone from Henry Moore to my then seven-year-old daughter, he never had a moment to drop me a line or three. It was only at the last moment of the book’s production that I stumbled across in my filing cabinet a forgotten bundle of the letters that he had been sending to me ever since my early childhood.

This was a shameful case of amnesia on my part, particularly as one of the letters consisted of a wonderful parody of a thriller that a friend of ours had just published. This letter represents the most enjoyable, precious and, being a single piece of paper, easy‑to-store item among all those I have inherited. It deserves to be quoted in full, but, what with moving house and so on, I can’t put my hand on it at this precise moment.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion