Labour and Conservative MPs have called for tighter restrictions on the use of vaginal mesh implants, in a parliamentary debate that heard how the lives of women had been avoidably blighted by complications linked to the surgery.

Labour has called for an immediate suspension of the use of the controversial implants, which are used to treat incontinence and prolapse, with the shadow health minister, Jon Ashworth, arguing that thousands of women have been exposed to unacceptable health risks. Tory MP Sarah Wollaston, a former GP and chair of the health select committee, said “an absence of data and cavalier practice” had exposed women to unacceptable risks and meant it had taken a decade for problems with mesh to be acknowledged.

Labour MP Emma Hardy, who called the debate, told MPs that the trials conducted before the introduction of mesh implants had been inadequate, and that pending a review of the evidence their use should be suspended.

Hardy urged the government to launch an independent inquiry into the “ongoing public health scandal” of serious complications suffered by many women who have been treated for urinary incontinence and pelvic prolapse.

More than a dozen MPs relayed harrowing stories of constituents who had suffered life-changing complications linked to mesh, including perforated organs, chronic pain and loss of sex lives.

Responding to the concerns, the health minister Jackie Doyle-Price announced that the publication of new guidance on the use of mesh by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice) would be brought forward from 2019 to later this year. Doyle-Price said she had been “horrified” to hear that women had been given implants without being made aware of the risks.

But she dismissed the need for an inquiry and said the health regulator, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, advised mesh was “still the best device for treating stress incontinence”.

“The issue is not the product, but clinical practice,” she said . “That’s what’s going wrong.”

Earlier in the debate, other Conservative and DUP politicians had joined calls for tougher regulations on the use of the devices.

The Scottish Conservative politician, Paul Masterton, rejected the suggestion that there was insufficient evidence to warrant the reclassification of mesh as a higher risk device, pointing to “women who have lost their careers, their husbands, their homes, their dignity and their lives, who are forced to spend day after day and night after night in agony”. “They are the evidence,” he said.

Wollastonsaid she did not support a ban on mesh procedures, but argued these operations should be performed at specialist centres and highlighted “appalling failings” in the consent process and the lack of evidence.

“These products were marketed aggressively without adequate clinical trials,” she said. “We need to ensure there are proper clinical trials just as we would expect for medicine.”

Owen Smith, a Labour shadow cabinet minister, who chairs the all-party parliamentary group on surgical mesh implants, said mesh injury was “one of the worst medical issues” he had come across as an MP, and had sprung from a failure to test devices before launching them on to the market.

“This story is quite simple... If this was a medicine that was leading in one out of 10 cases to sexual dysfunction or losing the ability to walk or work, it wouldn’t be on the market,” he said. “That’s how we need to look at it.”

NHS England said in a report in July that the treatment for urinary incontinence and prolapse was “a safe option for women”. However, since then further evidence has emerged about apparently high rates of complications.

The Guardian revealed in August that thousands of women have undergone surgery to have vaginal mesh implants removed during the past decade, suggesting that about one in 15 women fitted with the most common type of mesh support later require surgery to have it extracted due to complications.

MPs also heard that there are more than 100 devices currently on the market in the UK, most of which have never undergone extensive clinical testing, and which companies have withdrawn without warning.

Kath Sansom, a campaigner at Sling The Mesh, said: “People are waking up to the global scandal that is surgical mesh implants and at last it is on the political agenda at Westminster.”

Sohier Elneil, a consultant urogynaecological surgeon at University College Hospital, London, is calling for the use of mesh procedures for incontinence and prolapse to be stopped for two years. “The time has come for us to truly revisit everything we know about both these clinical states,” she said. “Clearly, the knowledge we have had to date has been limited both in scope and relevance. A change needs to happen now.”

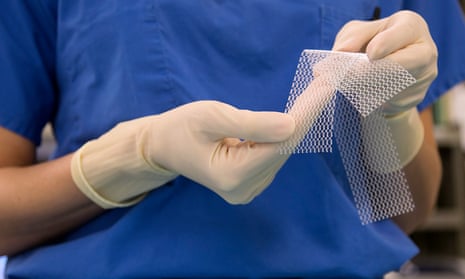

Q&AWhat is a vaginal mesh implant?

Show

The implants have been widely used as a simple, less invasive alternative to traditional surgical approaches for treating urinary incontinence and prolapse, conditions that can commonly occur after childbirth. For the majority of women the operation is successful.

However, concerns are mounting over the severe complications suffered by large numbers of patients, including chronic pain, mesh cutting through tissue into the vagina and being left unable to walk or have sex. Johnson & Johnson, whose subsidiary Ethicon produces one of the most widely used mesh products, is fighting a major class action in Australia. The Guardian revealed in August that thousands of women have undergone surgery to have vaginal mesh implants removed during the past decade, suggesting that about one in 15 women fitted with the most common type of mesh support later require surgery to have it extracted due to complications.