God, he’s good. After giving the Chinese president, Xi Jinping, an eight-year-old gelding from the French cavalry corps, President Emmanuel Macron has now wowed London with his loan of the Bayeux tapestry. These are masterstrokes of cultural diplomacy: generous presents that beautifully connect the life of nations, rather than assert either state dominance or highlight historic rifts.

Of course, there is a long history of loans and gifts between princes and governments. Famously, in 1515, the King of Portugal, Manuel I, was given a rhinoceros by Sultan Muzaffar Shah II, the ruler of Gujarat, and thought it so remarkable that he swiftly passed it on to Pope Leo X.

Sadly, the rhino died in a storm at sea, but descriptions of the animal provided the basis for Albrecht Dürer’s celebrated woodcut of a rhino. In 1793, Earl Macartney led a diplomatic delegation to the court of the Qianlong Emperor, laden with all the greatest wares of the British industrial revolution in the hope of opening up China for exports. Wonderfully, the emperor took one look at our clocks, vases, and globes and, surrounded by his own porcelain and jade, said he had no need for our trifles. In the 20th century, the Chinese took the habit to new levels with their own “panda diplomacy” strategy of dispatching their national symbols to zoos across the globe (two poor things were packed off to Finland only last week).

Margaret Thatcher had a different approach: she thought it amusing to hand President Mitterrand a first edition of Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities (with its accounts of guillotines and the storming of the Bastille) at the bicentenary celebrations of the French Revolution in 1989.

And then there are the snubs. While Gordon Brown painstakingly provided Barack Obama with a penholder crafted from the timbers of a 19th-century British anti-slaving ship, the president returned the compliment with a DVD box set that didn’t work on a British TV.

Museums do this type of diplomacy more effectively – such as when the British Museum lent the Cyrus Cylinder to Iran during a diplomatic deadlock, or the Science Museum’s leadership in Russia, or our own work building the V&A galleries in Shenzhen.

But as post-Brexit “global Britain” looms, we should be on guard for government ministers scouting our galleries for prospective cultural “gifts”. It would probably not be wise to open up some of the UK’s more controversial acquisitions – think Parthenon sculptures – but there are lots of other potential loans my colleagues and I need to be alert to.

For our EU partners …

If Brexit negotiations take a turn for the worse, I fear ministers might come for the V&A’s sumptuous collection of tapestries. Woven in Brussels in 1520, our eight-metre tapestry The Triumph of Chastity over Love probably belonged to Cardinal Wolsey (who wanted to remain in Europe) and then Henry VIII (er, who didn’t). Based on the poetry of Petrarch, it depicts Cupid bound at the feet of Chastity and might make the perfect loan to the European Commission as we seek to put all other temptations aside and agree a trade pact.

For Italy …

When it comes to Italy, there is, of course, an embarrassment of riches. Perhaps government officials might encourage the National Gallery to lend out the Giottos, Raphaels, Michelangelos, or perhaps Paolo Uccello’s The Battle of San Romano (1438). Not only is it one of the most dramatic and technically brilliant pictures of the Italian Renaissance, its loan to Florence could also see it united with one of its partner panels in the Uffizi Gallery, in a harmonious display of Anglo-Italian partnership.

For Donald Trump …

America is a trickier proposition. There is a set of Jacob Epstein busts of Winston Churchill that shift between the Oval Office and British embassy. But if I was Maria Balshaw at the Tate, I would put an extra lock on my Rothko murals. Commissioned for the Four Seasons restaurant in New York’s swanky Seagram Building (which, on Park Avenue, Donald Trump will kinda like), they ended up at the Tate in 1970 after the painter withdrew from the commission. Yet I still can’t see them in Trump’s White House.

For the Chinese …

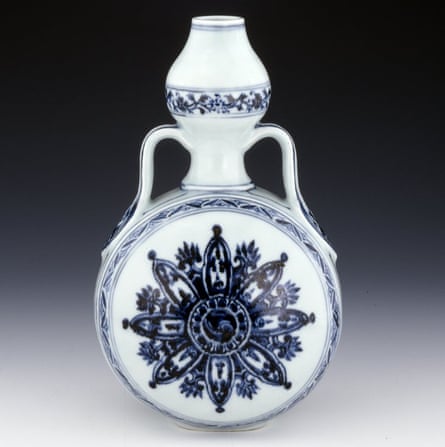

With Theresa May set to head to China at the end of this month, top of her list for the Beijing leadership might be the riches from the British Museum’s Asian collection. It was the attempt to imitate Chinese porcelain that inspired the British pottery industry in the late 18th century and the prime minister might be keen to lend one of the museum’s’s gorgeous bianhu moon flasks from Jingdezhen (the Stoke-on-Trent of China). This blue and white ceramic, decorated with lychees, is a stunning piece of Yongle period pottery – and a great example of the technology we sought so desperately to imitate.

For India …

Finally, to cement our future trading partnership with India, ministers might look to Cottonopolis and the remarkable collection of South Asian textiles held at the Whitworth Gallery. Manchester’s incredible array of historic fabrics and contemporary designs highlights the back and forth relationship between India and Britain when it comes to textile production. We also know that both May and President Modi like a bit of snappy dressing.

Tristram Hunt is director of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion