By Harish Damodran, Ankita Dwivedi Johri, Sreenivas Janyala and Partha Sarathi Biswas.

Between 2001-02 and 2016-17, India’s potato production has practically doubled, from an estimated 24.46 million tonnes (mt) to 48.61 mt. In case of tomatoes, it has tripled (from 7.46 mt to 20.71 mt), and for onions, quadrupled (from 5.25 mt to 22.43 mt). Also, the country’s total fruits and vegetable output of 271.09 mt last year almost equalled that of foodgrains (cereals plus pulses) at 275.68 mt.

It’s only fitting, then, that the latest Union Budget has proposed an Operation Greens — on the lines of Operation Flood for milk during 1970-95 — to address price fluctuations in potato, tomato and onions for the benefit of farmers and consumers. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has also declared his government’s intent to accord “TOP priority” to tomatoes, onions and potatoes, coining an acronym from the first letters of the crops.

While the specifics of Operation Greens — for which Rs 500 crore has been earmarked — aren’t known, there would seemingly be a lot of focus on the creation of cold storage capacity and processing infrastructure (the outlay of the the Ministry of Food Processing Industries for 2018-19 has been nearly doubled to Rs 1,400 crore). But will that address the real issue confronting horticulture — one of harvest-time gluts and off-season price spikes?

Probably not.

The current poor farmer realisations in potatoes, for instance, have little to do with lack of cold storage. The country already has around 32 mt of cold storage, much of it used to stock potatoes. The same goes for onions. In Maharashtra alone, almost 2 mt of storage capacity — which includes on-field raised platform structures (kanda chawl), owned by farmers — has been built under various schemes.

Nor can processing be a solution beyond a point. The best example here is sugar; it being a fully processed agro-commodity has hardly prevented recurrence of arrears in cane payment by mills to farmers.

The limits of processing would be even more in TOP crops. Pepsico, the maker of Lay’s and Uncle Chipps snack foods, procures some 0.3 mt of potatoes now through contract farming and open market purchases in India. Even adding others — ITC (Bingo), McCain Foods (which supplies to McDonalds), Balaji Wafers and assorted regional/local brands — won’t take the total to more than 1 mt, a fraction of the country’s 48 mt production. Moreover, the potatoes used for chips are of special processing-grade, with low sugar and high dry matter content, and not our regular table aloo.

What applies to potatoes holds for onions and tomatoes as well. It sounds nice to say that tomato growers’ income will rise four times if their produce is processed and marketed as puree or ketchup. Onions can also, likewise, be sold as paste or powder. But the question is: How much demand exists for that? At the end of the day, the bulk of TOP produced by farmers will have to be consumed as plain tamaatar, pyaaz and aloo.

A more sensible approach may be reviving the old idea of instituting a Market Intervention Agency (MIA), on the lines of the National Dairy Development Board vis-à-vis oilseeds and edible oils during the late-Eighties and early Nineties.

Today, we have no organised players in fruits and vegetables big enough to influence prices. Reliance Fresh does an annual business of 250,000-300,000 tonnes in this segment. The corresponding volumes of Aditya Birla Retail (More) and Mother Dairy (Safal) range from 100,000 tonnes to 150,000 tonnes each, and 50,000-75,000 tonnes for Big Bazaar and BigBasket. The largest onion and potato trader/commission agent at Lasalgaon or Agra, too, will not handle more than 150,000-200,000 tonnes in a year. This is unlike, say, milk, where organised dairies, both cooperative and private, procure about 30 mt, a fifth of India’s production. The presence of organised players reduces price volatility to that extent.

A well-funded MIA would procure TOP crops in major mandis during the peak harvesting/marketing season and offload the produce gradually in the lean months. Such a pan-India agency must not, however, end up displacing private trade, like the Food Corporation of India did. Its role should be only to curb extreme price volatility, a la the RBI’s interventions in the foreign currency market. The MIA should buy potatoes from Agra at Rs 15/kg in February-March, to sell not at Rs 4-5 but maybe Rs 20-25/kg in July-August.

The government could also do away with stockholding, export and other trading restrictions. Once this happens, other government initiatives — be it promoting farmer producer organisations or connecting mandis through an electronic national electronic market to allow seamless flow of price information — will fall in place and pave way for a genuine Operation Greens.

Tomato

Prices unsteady, Andhra tries a seed experiment

Madanapalle, Andhra Pradesh; India’s largest market for tomatoes

Only four persons among the younger generation in the 200-odd families of Vanamaladinne village near Madanapalle, which houses India’s (and probably Asia’s) largest market for tomatoes, are into farming. The spacious, brightly painted houses of the village, with SUVs, sedans and mini-trucks parked outside, suggest affluence born of the crop. But the unpredictable market and price volatility mean that many feel the compensation isn’t worth the risk.

S Venkata Ramana Naidu, one of Vanamaladinne’s well-known farmers, points to the price fall over just two months: from Rs 25-plus per kg to Rs 4 now. Last year, on the other hand, from April to November, a shortage meant tomato prices were consistently Rs 25-30 per kg, occasionally even crossing Rs 60.

Even at Rs 10 per kg, Naidu says, farmers can make a profit of Rs 1.25 lakh per acre. But any rate below Rs 5 means losses.

The favourable climate — neither too hot nor too cold — ensures tomato grows well in this region that’s at the intersection of Andhra, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, spread in a 100-km radius around Madanapalle in Chittoor district. Prices start rising towards March when tomatoes grown near Delhi and Uttar Pradesh get exhausted. It takes 72 hours for tomatoes to reach Delhi markets from here.

Ismail Baig at the Madanapalle market, after not getting enough price to even cover cultivation costs (Express Photo/Harsha Vadlamani)

Ismail Baig at the Madanapalle market, after not getting enough price to even cover cultivation costs (Express Photo/Harsha Vadlamani)

Naidu, whose tomato fields are irrigated by a drip system, with a special plastic mulch covering the soil to retain moisture, sells at either Madanapalle or the Kolar marketing yard in Karnataka. “When prices go up during summers or when the crop has failed elsewhere, we get good rates… Medium and big farmers can negotiate these price fluctuations, but small farmers end up in debt,” he says. “Some farmers leave the tomato in the fields to rot because the money is not enough to even cover the cost of labour to harvest. Transport charges and the 4 per cent commission fee on the sale price to agents are over and above this.”

Ismail Baig from Kandukuru of PTM Mandal, Chittoor district, who grows tomatoes on 1.5 acres, says that to get 160 boxes of tomatoes (28 kg each) to Madanappale, he paid Rs 22 per box as transportation and other charges. After two hours of bargaining, he got Rs 100 per box. “It was not enough to recover even my cultivation costs,” Baig says. Balineni Ravindra Prasad of Vanamaladinne is among those who has left his ripe tomatoes for now on his 5-acre field.

A Subbaraghava Raju, Secretary of the Madanapalle Agriculture Marketing Yard, admits that price fluctuations can devastate farmers, and hence welcomes the Union Budget’s proposal of tax breaks for farm producer organisations (FPOs), formed by them. “FPOs can help farmers unite and negotiate a steady price,” he says. However, he admits, “Medium and big farmers may not be interested, as they can afford to take losses but may not be willing to give up the quick money they make when prices go up suddenly.”

S Naidu (left), who failed to get son to take up farming, is raising a mango orchard as a retirement plan (Express Photo/Harsha Vadlamani)

S Naidu (left), who failed to get son to take up farming, is raising a mango orchard as a retirement plan (Express Photo/Harsha Vadlamani)

As for the suggestion by the Andhra government that they take recourse to food processing units, farmers say it is not practical right now. “Such units come to yards to purchase only when stocks are being sold at throwaway prices. If the government sets up factories for tomato puree or ketchup or juice, they should purchase the stocks at prices that are beneficial to all parties. Then we would sell entire stocks to factories from the farm itself,” says farmer K Ramana of Chittoor.

Secretary Raju contests this claim of private players benefiting, pointing to the downed shutter of Reliance’s procurement office at the Madanapalle market yard. “Their procurement here is over. Now they are purchasing vegetables in Karnataka for their outlets. If there is a glut in the market, even at Rs 2 or 3 per kg, there won’t be many buyers.”

The Andhra Pradesh government has started a programme to address the fluctuating tomato prices. Horticulture Commissioner Chiranjeevi Chowdhary says they have tied up with Japanese company Kagame, which is supplying seeds on an experimental basis to grow tomatoes that can be used in food processing factories globally.

Anji Reddy, a big farmer owning 20 acres, has sown this seed on 5 acres. “If the experiment is successful, all farmers can sow two varieties — one for the open market and the other for food units — and prevent excessive production and price fluctuations,” Reddy says.

Meanwhile, it is hard to find a farmer below 45 years in the over 1,500 acres of cultivable land in Vanamaladinne. Naidu says he tried very hard to persuade son Sukumar to join farming, but he chose engineering and now works at an IT major in Bengaluru. Prasad, whose son too works for a corporate in the city, laments that he chose the Rs 20,000 per month job over the family profession.

Many of the elders are now seeking retirement security in mango orchards. “We are reducing the acreage under tomato and other crops and started growing mango trees. Once the trees grow, they don’t need much care. After a few years, the orchards will start paying rich dividends,” says Naidu, who is growing mango on 5 acres.

Prasad, who has also done the same, says he welcomes the Centre’s suggestions. “But it will take sustained effort from governments to bring back confidence in farming… The Centre’s measures will take at least a decade to trickle down.”

Onion

Nashik, Maharashtra; In state producing most onions, 60% grown here

As Santosh Gorade, 38, tends to his 3.5 acres of onion crop, he says he will do this for “maximum six-seven years more”. After that, the farmer from Takli Vinchur village in Nashik plans to get out of farming. “It’s too volatile and market forces are always against us,” he sighs. Under no circumstances, he adds, does he want his two sons, Pranav, 10, and Karanvir, 5, to take up farming. “There is no future in this.”

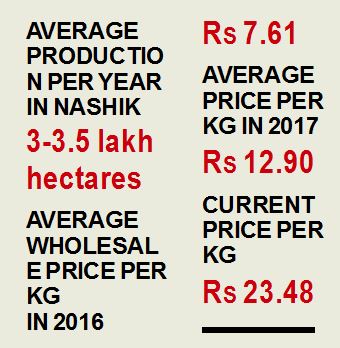

In the past two years, this volatility in the markets has left onion farmers battling penury. Maharashtra is the largest producer of onions in the country, contributing 30 per cent of the total, while Nashik accounts for 60 per cent of the onion area in the state. Nearby Lasalgaon is the largest wholesale onion market in the country.

Gorade says the Budget this year, with its Operation Greens, or PM Modi’s TOP talk, mean little, when the biggest villain for onion farmers is the government. Regimes have been known to fall on onion prices, and farmers complain of the government repeatedly intervening to bring prices down in times of flush, and staying silent when prices plunge.

“Before launching Operation Greens, someone should explain why onion keeps being put under the Essential Commodities Act. This allows the government to declare stock limits and intervene for price manipulation,” says Gorade. “We know onion is a politically sensitive crop, but the farmer too must be thought of.”

At Lasalgaon, the country’s largest wholesale onion market (Express Photo/Mayur Bargaje)

At Lasalgaon, the country’s largest wholesale onion market (Express Photo/Mayur Bargaje)

Before the Gujarat elections in December 2017, the Minimum Export Price (MEP) of onion was set at a whopping $850 per tonne, a move meant to discourage exports to stabilise prices. Dipak Pagar, director of the Nampur wholesale market in Nashik, says, “Days earlier to it, the average traded price of onion was around Rs 35 per kg. After the MEP, prices corrected to Rs 25-24 per kg.”

That MEP was removed only early this month.

Till two years ago, Gorade would grow onion all three seasons — kharif (June-July, with harvest in September), late kharif (September-October, with harvesting post-December) and rabi (December-mid January, with harvest post-March). It’s only the rabi onion which is amenable to storage, and it’s this onion that feeds the market from April till new produce hits the markets after August.

Heavy losses in 2015-16 broke the onion cycle for Gorade. “I was forced to sell my rabi onions for Rs 2-3 per kg, against production cost of Rs 9.50, which wiped out my savings and left me in debt,” he says. In 2016, Gorade kept away from onion and diversified part of his land to develop a nursery.

Santosh Gorade, who also grows grapes, says he wouldn’t want his sons to do this work ever (Express Photo/Mayur Bargaje)

Santosh Gorade, who also grows grapes, says he wouldn’t want his sons to do this work ever (Express Photo/Mayur Bargaje)

But in 2017, Gorade’s vineyards suffered heavy losses due to rains, while onion prices firmed up in June, and so he is giving onion another shot.

Gorade notes that the low prices in 2015-2016 followed another announcement of MEP, at $300 per tonne, in end-2014. “Prices fell and remained low, despite the government removing export restrictions by end of December 2015,” he says.

In November 2017, apart from the $850 MEP, the 38-year-old says, “For the first time in Nashik, Income Tax sleuths conducted raids to look for stored onions at traders’ godowns.”

About the removal of the MEP a few days ago, Gorade says, “By far, it was the fastest removal of MEP I have seen in my 20 years of onion trade. If it had not been done, the markets would have seen a bloodbath.”

Of India’s average production of over 200 lakh tonnes of onion, more than 180 lakh tonnes is consumed at home. Just about 10-15 per cent is exported. In 2017, till October, before the MEP was imposed, 16.79 lakh tonnes of onion had been exported.

Farmers from Takli Vinchur normally take their produce to the Lasalgaon wholesale market. Onion is currently trading there at Rs 18.46 per kg, down from Rs 28.62 kg in January. Gorade is not sure if the prices will last, given that another bumper crop is in the offing.

About the possibility of post-harvest processing of the bulb, Gorade says, “Onion powder has demand in Europe, but who will buy it in India?”

Above all, he adds, what onion farmers need is for the sector to be freed of frequent government intervention. “It becomes news when onion prices go up, but when we suffer, there is hardly any attention, both from the media and government.”

Potato

Ahead of harvest, memory of rotting potatoes in 2017 leaves farmers ‘nervous’

Hathras, west Uttar Prades; one of the top three potato-producing districts in India

On Budget day, the entire village gathered around potato farmer Mahendra Singh’s “Phillips TV” to hear what the government had in store for them. Buffeted by demonetisation at the end of 2016, followed by low prices all of last year, they hoped for some relief.

Mahendra says they were sorely disappointed. “Har saal ekaheen cheez bolte hain (They say the same thing every year),” says the 65-year-old.

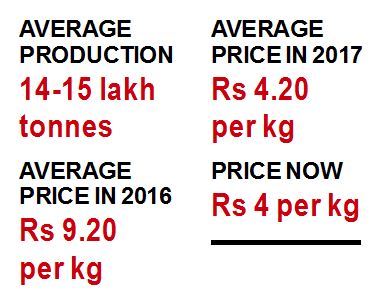

Nagla Hira Singh village lies in Hathras tehsil which, together with Aligarh, Mathura, Agra, Firozabad, Etawah, Mainpuri, Kannauj and Farrukhabad in south-west Uttar Pradesh, accounts for roughly a fifth of India’s potato production of around 480 lakh tonnes (lt) a year. Eighty per cent of the village’s population of 270 is involved in potato cultivation.

With another round of harvesting set to begin from February 20, the farmers all across complain of the same — high production, low remuneration and indifferent government. And of mounds of potatoes left to rot in cold storages, or simply discarded, last year.

Hathras District Horticulture Officer Gampal Singh says that of the 14-15 lakh tonnes (lt) of potatoes produced in Hathras in 2017, 95 per cent were “out of cold stores”. “Most of the potatoes were sold at low prices in mandis. Not much was discarded,” the officer insists.

Chandra Vir, who let go of 80% of his produce last year, checking on his ripe potatoes (Express Photo/Amit Mehra)

Chandra Vir, who let go of 80% of his produce last year, checking on his ripe potatoes (Express Photo/Amit Mehra)

The potato farmers here sow the tubers in October, and harvest them starting around now, till March. Only about 10-15 per cent is sold immediately, and the rest is kept in cold storage, to be released as per prices. To stock their produce from February-March till November 30, cold storage owners charge farmers Rs 110 per bag, says potato farmer Chandra Vir.

Carefully walking in the furrows of his 70-bigha (14-acre) field at Nagla Hira Singh, amidst ripe potatoes that are starting to peep out, Chandra Vir admits he is “nervous”.

Last year, he had harvested 40 bags of 50 kg each per bigha, against 25 bags in 2016. “But I could sell only 20 per cent of my 2,800 bags. Since the potato price couldn’t cover the cold storage charges, I just left my produce there,” says the 36-year-old father of two.

Om Vir Singh, who has a 20-bigha plot, says their troubles began with demonetisation in November 2016. “Since most traders pay in cash, there were no sales for a month.” Things haven’t looked up since, according to the 25-year-old.

At Agra, India’s largest market for potatoes, 60-odd km from Hathras, potato prices averaged about Rs 4.20 per kg in 2017, less than half the year before. Current rates are just Rs 4 per kg.

Rajendra Gaur at his three-storey cold storage, which is currently undergoing repairs to receive the fresh harvest. (Express Photo/Amit Mehra)

Rajendra Gaur at his three-storey cold storage, which is currently undergoing repairs to receive the fresh harvest. (Express Photo/Amit Mehra)

Counting input costs like labour, irrigation, fertilisers and transport (to cold storage), Om Vir says, “It costs Rs 10,000 to cultivate potatoes on 1 bigha land. Ab aloo agar kaudiyon ke daam bikega toh kisan kya kamaayega (If potatoes sell for peanuts, what will a farmer earn)? For the past two-three years, we have failed to recover even our cultivation costs.”

While Hathras has 154 private cold storage units in all, Nagla Hira Singh alone has three.

Compared to Chandra Vir and Om Vir, Mahendra, a bigger farmer, with 200 bighas, was less devastated by the low prices, though his “4,000 bags out of 6,000” went waste.

The farmers are aware of the new Operation Greens for horticulture crops, and of the PM’s “TOP” promise. But, says Om Vir, “Kisan toh Operation Greens samajh nahin paaya (The farmer has not understood Operation Greens). No official has come to us yet.”

In the absence of official communication, such a plan seems to them as ill-conceived as the BJP government’s promises in the state. In April last year, with prices staying low, it said that state agencies would purchase 1 lakh metric tonnes at a support price of Rs 487 per quintal; three months later, it declared a subsidy for farmers to take potatoes to other states.

Chandra Vir explains why the schemes didn’t help. “They wanted only large- to medium-sized potatoes, plus had other specifications. Most of our potatoes did not fit the bill. And as for sending potatoes to other states, no one needs them anymore… West Bengal, Gujarat etc all grow their own potatoes. Also, the subsidy couldn’t have covered the costs.”

Horticulture Officer Gampal Singh agrees there is little demand for UP’s produce now. “We had suggested that farmers grow papaya, tomato, capsicum, roses etc. But these need a lot more work and the farmers are not willing,” he argues.

About the state government’s purchase plan, the officer says four centres were set up in Hathras. However, the total procurement of potatoes from the district was just 120.5 quintals — less than the individual harvest of most farmers!

The farmers have been struggling to pay not just cold stores but also bank loans. “We usually borrow against our Kisan Credit Cards before the sowing season, around Rs 6-7 lakh… I haven’t been able to pay that,” says Mahendra.

Measures such as loan waivers are no solution, says Chandra Vir, nor are suggestions that farmers set up processing facilities. “How are we going to run potato chip plants? Setting up even a small plant will mean more loans… Aur ab Modiji ne TOP bol diya… Ye bolne waali sarkaar hai (And now the PM has said TOP… This is a government of claims).”

Over at the Shri Radhe Giriraj Cold Storage on the Mathura-Hathras road, owner Rajendra Gaur is preparing to receive the fresh harvest. “Last season, we had stored 1.15 lakh bags from 300 farmers; 40 per cent never came to take the potatoes. We lost about Rs 30 lakh. We fed the potatoes to animals,” he says.

Chandra Vir fears that such setbacks are killing farming. “The problem today is there is no pride in farming. I will not let my children do the same,” he says. A Class 12 pass, he sends his children to a “convent” school. “I pay Rs 1 lakh fees annually. Last year I borrowed the money.”