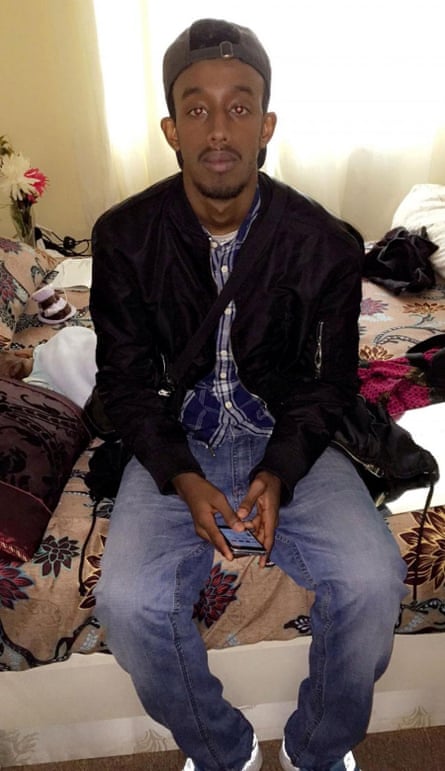

It is highly likely that Khader Ahmed Saleh felt fear in the weeks before he was murdered. And if he did, the wiry young father from London’s tight-knit Somali community would not have been alone. In a recent survey, more than two-thirds of his fellow inmates inside Wormwood Scrubs prison admitted feeling unsafe. That finding was published weeks before Saleh was stabbed to death on the afternoon of 31 January.

Last Thursday Saleh’s family and friends assembled outside the west London prison, demanding answers in relation to another violent tragic episode inside the UK penal estate; one that has left three inmates charged with murder.

As they protested and mourned, the distinctive Victorian towers of Wormwood Scrubs loomed large. Behind its high, weathered brick walls, living conditions have plummeted to a level which should shame a wealthy 21st-century society.

According to a report by the chief inspector of prisons published 53 days before Saleh, 25, was murdered, rats and cockroaches routinely gorge on litter dropped from broken windows into the prison yard. Conditions in the Victorian-era C wing, where Saleh died, were so chaotic that food routinely ran out and inmates survived on “mountain survival” dried-food packs.

Those who have observed the prison estate at close quarters have been uniformly shocked by what they have witnessed and what they have been told. Peter Clarke, a methodical, down-to-earth detective who once ran Scotland Yard’s Counter Terrorism Command, was asked by the Ministry of Justice in 2016 to investigate the prison estate. He notes as a matter of “particular concern” the 40 to 50 violent incidents each month. Every two days a member of staff is assaulted.

Prison officer David Todd has patrolled both Wormwood Scrubs and served in the British infantry in Derry during the Troubles. The 47-year-old has little doubt which was the more intimidating. “I feel more vulnerable walking the landings in British prisons than I did walking the streets of Northern Ireland,” he says.

Even after 27 years of life as a prison officer, Todd describes the narrow walkways of Wormwood Scrubs as “very daunting”. In some jails, he adds, one officer is left to oversee 100 inmates.

Organised gangs hold huge power. It is, says Todd, the precise opposite of a controlled environment. Or at least of one controlled by the state.

Ex-offender and former drug abuser Mark Johnson founded the charity User Voice to encourage prisoner rehabilitation. “Being incarcerated in this country at the moment,” he says, “is being in a system tantamount to torture. You’re in a place of chaos. You may have left behind a life of chaos but it’s like going from frying pan into the fire.”

Overpopulated, under-resourced, drug and pest-infested and terrifyingly violent, no public institution in England and Wales, according to expert consensus, has deteriorated more dramatically and more profoundly in recent years than our prisons.

Todd has seen many things he wants to forget but cannot. Once he watched an inmate smoke spice, the synthetic drug that renders users catatonic, before flinging himself headfirst off a second-floor landing, arms by his side, making no attempt to break his fall. He found a prisoner in the kitchen in a Kent jail with his stomach sliced open. He remembers an inmate with mental health problems who would sit in his cell, silently eating his own faeces.

Government data published six days before Saleh was murdered confirmed that prisons in England and Wales have never been more dangerous. Assaults and serious assaults are, according to the Ministry of Justice, at record levels. In the 12 months to September 2017, 28,165 incidents were recorded – a 12% increase. Of those, 7,828 were assaults on staff. The rate of attacks continues to escalate. During the last quarter of 2017, another high was set with assaults rising to 86 a day, 24 of them against staff.

Independent analysis by the Observer of 220 official prison inspections, covering 118 adult jails in England and Wales, found that more than two in five were unsafe for prisoners.

Self-harm inside prisons has also reached record levels – there were 42,837 incidents during the year to September, an increase of 12%. On an average day, there will be 117 such incidents. Eight inmates will be hospitalised. Someone takes their own life in prison every five days.

Todd says prison officers quickly become accustomed to dealing with the “shocking” loss of blood after an inmate slices their wrist with a razor.

Since October, the parliamentary justice committee has been investigating what no one now denies is a crisis in our prisons. According to Bob Neill, the committee’s Conservative chairman: “We really need to have a serious conversation about what we use prison for. Society has to think about that.”

Neill cited a vignette from a recent inspection of HMP Liverpool as illustrative of the challenges facing the penal estate. “The inspector went into one cell where the shower wasn’t working, the lavatory was broken and flooding. There was a mattress with a guy on it with mental health problems who had been there for six weeks. How much of our prisons now are just warehousing for people with mental health and other issues?”

One answer to that question comes from the Criminal Justice Alliance, which estimates that 21,000 mentally ill people, a quarter of the current jail population, are currently imprisoned, competing for just 3,600 high-security and medium-security beds reserved for mental-health patients in English prisons.

The British Medical Association says the average life expectancy of a prisoner in England and Wales is 56, less than conflict-ridden, poverty-stricken South Sudan. The statistic, warns the BMA, is “a worrying reflection of the overall wellbeing of those in the secure estate”.

At the root of so much squalor, violence and distress is one inescapable truth: we are as a society incarcerating too many people.

Official data revealed on Thursday that the number of prisoners in England and Wales rose to 84,255 – the highest imprisonment rate in western europe. A quarter of a century ago in 1993, the prison population stood at 44,552.

Two-thirds of prisons are officially overcrowded.

Lord Woolf, the former lord chief justice who wrote the report on the 1991 Strangeways prison riot, said that a complete government rethink was required, beginning with the need to address overcrowding.

“I’m afraid we’ve got to have a complete reassessment of the situation. Although you can’t change the situation overnight, there has been a complete breakdown in recognising the fact that serious action is needed and recognising that the only way to do it is to have a long-term plan.” If any plan is to succeed, the prerequisite will surely be a reversal of the deep cuts that have stripped away thousands of experienced prison staff. Between 2012 and 2016, as the prison population rose, frontline staff fell by more than 7,000. A commitment to recruit 2,500 new prison officers has since been made, but Todd feels it is nowhere near enough.

Between 2016 and 2017, 57 prison officers left their jobs but only 21 were replaced. On C wing, where Saleh was killed, supervision problems were noted. Lack of staff meant too many prisoners were locked up in their cells, some for as long as 23 hours a day.

Denied any purposeful activity, prisoners become desperate to kill time. Drug use has escalated, in particular the use of spice, the synthetic cabannoid described by the Prisons and Probation Ombudsman as a “game-changer” capable of quickly transforming a passive inmate into a dangerous aggressor. Todd said: “It makes someone who is normal into an absolute animal. It’s hideous.”

Quick GuideBritish jails in jeopardy

Show

Overcrowding

The current male and female prison population is 84,255, having almost doubled in 25 years. Analysis suggests jails in England and Wales are holding more than 10,000 prisoners than they were built for, with two-thirds of prisons classified as overcrowded.

Self-harm

Currently at record levels, with 42,837 incidents – an average of 117 a day – documented during the year to September, an increase of 12%. Already it looks like it will be higher this year with 11,904 incidents recorded during the last quarter, equal to 130 a day. Eight inmates a day will be admitted to hospital. There is a suicide in prison every five days.

Assaults

Again, at record levels with 28,165 incidents documented during the 12 months to September 2017, a 12% increase. Of these, 7,828 were assaults on staff . Already at unprecedented levels, the rate continues to escalate. During the last quarter of 2017, another record high was set with assaults rising to 86 a day.

Staffing numbers

The Ministry of Justice is now increasing prison officer numbers following dramatic cuts. Latest figures reveal a rise from 17,955 in October 2016 to 19,925 in December 2017. In 2010 there were 27,650.

Reoffending rates

The number of adults reconvicted within a year of release stands at 44%. For those serving sentences of less than 12 months, this increases to 59%.

Clarke found drugs were “easily accessible” inside Wormwood Scrubs. The wing where Saleh died contained the prison’s unit for dealing with inmates needing help with substance misuse.

Given what amounts to the slow-motion meltdown of the prison estate, Rory Stewart, the new prisons minister, faces instant pressure to make an impact. Battle-hardened observers are already sceptical. Frances Crook, chief executive of the Howard League for Penal Reform charity which campaigns for change, recently met Stewart. “As he pointed out, this is his fourth or fifth job in two years. He says he doesn’t know how long he is going to be there – and we’ve had six secretaries of state in seven years.

“No wonder the system is in chaos. It’s a shambles.”

Many agree that Stewart’s initial challenge is to somehow cap, then lower, a prison population which is proportionately twice that of Germany’s. In the longer term, other issues require fixing: namely how to deal with the specific challenges of a fast-growing group of older prisoners aged over 60, largely driven by historic sex offending. Other demographic issues also need to be addressed, the chief of them being why there are so many black and ethnic minority people among the prison population.

If the demographic makeup of inmates locked up reflected those of England and Wales, there would – as the Labour MP David Lammy recently noted – be 9,000 fewer black and ethnic minority people in prison, the equivalent of 12 average-sized prisons.

Stewart must also urgently examine future prison privatisation. The Ministry of Justice expects the private sector to play a role in running prisons, but after a period of cross-party consensus, support for this is now waning.

Among one of the less reported failures of Carillion, the government contractor which folded last month, was its role in maintaining Wormwood Scrubs. So hapless was its performance that the firm was deemed to represent “a threat to the security of the prison”.

On the basis of his visits to HMP Liverpool, Peter Clarke made a series of recommendations for improvements in our jails, emphasising among other things the urgent need to address the issue of overpopulation.

On Friday a justice committee report condemned the government for failing to act on his advice. He is reportedly exasperated by the lack of a coherent response from Whitehall.

Campaigner Mark Johnson said simply: “Report after report of evidence is being unearthed and yet nothing is changing. We need to start asking the question: what is prison for? We need to talk about what is happening.”