White people in America tell themselves many stories about racism and race. Some are comforting myths, designed to naturalize racial hierarchies or dispel the guilt and responsibility of privilege. Others are sociological and historical narratives, which locate the causes of racism in specific times, places and institutions, so that the problem of racism can be quarantined, and more easily cured.

But there is another, mostly overlooked story in which the causes are more diffuse and more difficult to accept – one that goes a long way towards explaining our recent racial tragedies.

A high level of segregation of black people in black neighborhoods and white people in white neighborhoods is an observable phenomenon in the United States. As narrative-making machines, we seek to explain it.

One explanatory story, frequently told by my students early in the semester, is that people “like to live with their own kind”.

This simple, catchy causal story naturalizes what could otherwise be an ugly manifestation of racism and has the benefit of reflecting the preferences of the students and their many communities: many of them are indeed happy living with their own kind.

Yet the explanation can’t account for the peculiar level of racial segregation between black and white people in America.

First, only those two groups are so segregated: we can use census data to measure the level of segregation of various racial, ethnic, and immigrant groups (with measurements like the segregation index, an index of isolation, and other calculations), and Asians and Latinos are much more likely to live in diverse neighborhoods than either whites or African Americans.

City by city, the highest levels of segregation for immigrant groups are actually lower than the lowest levels found for African Americans, and this has been true for a hundred years.

Among other groups, the richer one gets, the less one lives in an enclave concentrated with members of one’s own group: as generations of Chinese or Mexican families move up economically, they move out of Chinese or Mexican neighborhoods.

In contrast, wealthy African Americans live in neighborhoods that are nearly as black as the poorest African American neighborhoods: segregation works differently for black Americans than for other groups.

Social scientists have developed a second story about segregation to better explain this phenomenon.

Douglas Massey and Nancy Denton contradict the idea that people like to live with their “own kind” in their landmark study of racial segregation, American Apartheid: until the 1920s in America, African Americans lived in mixed communities with other groups.

Even today, African Americans don’t express a preference to be as segregated as they are: in surveys, the largest percentage of African Americans want to live in neighborhoods that are a 50-50 mix of black and white people. But few such neighborhoods exist, and almost none stay mixed for long.

This second explanatory story of segregation suggests that government and business implemented policies that separated blacks and whites.

Laws prohibiting black people from living in white neighborhoods were tried out in many cities before being ruled unconstitutional after an early NAACP challenge in 1914. Afterward, the National Association of Realtors maintained a policy instructing members not to sell homes in white neighborhoods to black buyers.

Banks exercised similarly restrictive policies, not lending to black people at all or looking at the race of the borrowers and neighborhood before making a loan.

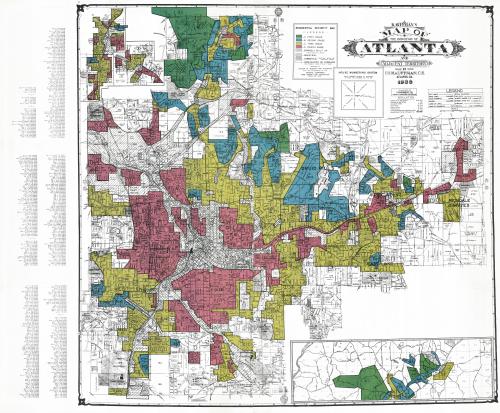

An early government homeownership program, the Home Ownership Loan Corporation, drew color-coded maps and explicitly labeled mixed-race neighborhoods as “hazardous”. (The Mapping Inequality project at the University of Richmond recently uploaded 1930s redline maps for cities around the country, providing a block-by-block snapshot of the racially and ethnically determined real estate valuation.) Realtors and rental agents may steer black people looking for a home away from white areas as often as one in every three visits.

The response to this story of segregation has been the Fair Housing Act and other laws prohibiting discrimination by landlords, banks, and realtors. Laws against discrimination serve an important purpose; otherwise, African Americans and other people of color pay more for housing, are given more expensive loans, are restricted to all-black schools, even pay higher taxes and see their homes stagnate or decline in value.

But it’s not clear that existing laws have been effective at reducing deeply entrenched discrimination, an additional reason to think story two doesn’t help us explain racial discrimination.

There’s a third story about segregation that doesn’t get told very much, although the facts are in plain sight.

What is sometimes called the ghetto, a large, almost entirely African American neighborhood near the center of many US cities, is a creation of violence.

As African Americans moved to northern cities during the Great Migration of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, they were kept out of many areas and squeezed into increasingly crowded, poorly maintained neighborhoods.

In city after city in America, in the 1920s, white resentment of the growing black population boiled over into race riots in which white citizens and police attacked, beat, and killed black residents, damaged black businesses and burned black homes and institutions.

In the ignominious (but largely forgotten) race riots of Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1921 more than 300 people were killed in attacks that included police dropping incendiary bombs from aircraft on to areas where black people lived.

African Americans were forced, as a defensive strategy, to leave the scattered mixed-race settlements that they lived in and retreat into large all-black neighborhoods that could provide some measure of protection from marauding whites and dangerous forces of law and order.

The danger of straying outside these majority-black neighborhoods is not in the past.

Today, African Americans identify plenty of places they wouldn’t want to live. One resident in the suburbs of Baltimore told me proudly that he looked for a house all of five miles past where he lived, a place “most blacks don’t go, because you know, there could be problems there”. What they worry about, he said, was the Klan.

Anyone who lives in a black neighborhood can name nearby white neighborhoods with reputations for intolerance, prejudice and violence where they’d rather not go.

Even in less-hostile territory, African Americans find the prospect of being constantly judged by white neighbors – and having to be on their best behavior to disprove white stereotypes – tiresome.

One Washington-area resident said, “I really wasn’t interested in moving into an all-white neighborhood and being the only black pioneer down there. I don’t want to come home and always have my guard up. After I work eight hours or more a day, I don’t want to come home and work another eight.”

Well-to-do African American professionals don’t want to live in well-to-do white neighborhoods because they’ll be harassed by the police who are suspicious of any black person driving through the area. An African American judge once recounted to me the number of times her husband was stopped, and followed home, after coming home from work or evening church meetings.

This third narrative – that black people mostly live in overwhelmingly black neighborhoods because white neighborhoods are unsafe for black people – breaks the mold of stories we prefer to tell.

The first makes the segregation seem natural, so that nothing need be done.

The second gives people the evidence they needed to propose fair housing legislation, and the sense that they have solved the problem.

The third narrative suffers from a diffuse actor: not a bad apple here or there, but a hostile white society that was far more daunting to tackle and difficult to legislate away. Such a story fails to gain traction because it lacks a moral explanation of the sort a white narrator is likely to want to convey.

As recent shootings by the police – of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri; Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Florida; Philando Castile in Falcon Heights, Minnesota; John Crawford in an Ohio Walmart – show, something has changed in America today. Today, stories of violence against African Americans come not just from the inner city, but the suburbs.

In the hundred largest metropolitan areas in the United States, half of African Americans live in the suburbs, not the cities. Suburbs were never as lily-white as their reputation, but today they’re even more diverse. Black families have transcended the color line.

But some police and white residents haven’t.

In the 1990s, police brutality headlines came from cities: Amadou Diallo was shot to death by the NYPD in the Bronx; Rodney King was beaten by the Los Angeles police. Today, the stories come from areas in transition, according to research by sociologist Richard Moye and his colleagues. They’re not all black or all white areas. They’re closer to an even mix. Ferguson, Missouri, is 67% African American; Sanford, Florida, is 30%.

These dangerous encounters happen at borders where black and white neighborhoods mix. Former college football player Jonathan Ferrell got in a car accident, knocked on a door for help, was mistaken by the resident for a robber, and shot by police. It happened in a Charlotte, North Carolina, suburb with a 40% black population, where a black community ends and a white rural area begins.

In a white Dayton suburb next to a mixed black-and-white neighborhood, John Crawford was strolling through a Walmart chatting on the phone with his girlfriend. He picked up a pellet gun from the toy section. Shoppers called police because they thought he looked like a threat. Police shot him with little warning while the end of the gun was leaning against the floor.

Eric Garner’s death in Staten Island shows police violence against black people still happens in cities, but even that happened in a comparatively mixed part of the borough (27% black population).

The problem is, some residents and police haven’t updated their image of their new neighbors from the scare stories they told each other when the neighborhood was all white.

The 19th-century Black experience was rural. The 20th-century black experience was urban. The 21st-century Black experience will probably be suburban.

We need to make those new neighborhoods safer for new black residents. That begins with changing outdated white stories.

Researchers David Jacobs and Robert M O’Brien found that police shootings were more likely to happen in areas where African Americans made up a growing percentage of the population, but were less likely in areas with a black mayor.

In other words, police shootings peak in the middle: beginning with an all-white area, they rise as the black population begins to get bigger but is not large enough to be politically dominant. When the black community is large enough to have significant political influence, fewer shootings occur.

To black families living in black neighborhoods, the view beyond the black community looks dangerous. Just as the “realtor discrimination” explanation provided narrative justification for legislation against housing discrimination, a narrative of the dangers lurking in mixed neighborhoods supports growing actions against police violence by groups like Black Lives Matter.

The movement is not just an effort to punish police abuses, just as the Fair Housing Act was not just legislation to catch discriminatory real estate brokers. Making it difficult for the police to violently control or harass African Americans in public space takes away a process that has contributed significantly to the ongoing residential segregation of African Americans, and the negative consequences that spring from it.

In the meantime, if black families are hesitant to move into mostly white neighborhoods, policymakers should think twice before pushing them into those areas.

The federal Moving to Opportunity program gives low-income households incentives to move out of large housing projects and into more economically mixed neighborhoods, on the theory that poor families will do better if they lived in mixed areas where schools are likely to have more resources, where crime may be lower, where neighbors are likely to have jobs with better-paying employers who may have job openings.

Indeed, some initial studies showed that Moving to Opportunity was working: participants were earning a few hundred dollars more a year. Later studies that charted the long-term effects determined that wages were not improved for parents who moved, and outcomes may even have been worse for teenagers who moved.

Kids under 13, however, grew up to make $3,000 more a year – a big chunk compared to the $11,000 they were likely to make otherwise.

The policy, of course, targeted low-income people not black people, but in many cities it was seen as a way to de-concentrate poverty and disperse mostly black housing projects. (In cities, black poverty is concentrated, white poverty is dispersed. There are actually more poor white people in New York than poor black people, but census maps show they’re spread across the whole city, except in black neighborhoods.)

I want our neighborhoods to be integrated, and I appreciate that the government is doing something, for a change, to desegregate them. But we should pause: because poor people have so few options, they often have to make difficult tradeoffs to receive public benefits in exchange for certain behaviors.

For example, when welfare payments were made only to families with no father in the house (and case workers arrived without warning to look for evidence a man was living in the home), families had to choose between an intact family with two parents, and a father who lived elsewhere in exchange for a little of the money the family so desperately needed.

In the case of efforts like Moving to Opportunity, we should at least ask how hard we should push poor families into new neighborhoods: a few hundred dollars is nothing compared with the worry that you, your spouse, or your kid will be harassed by the police, or the concern that your child will be singled out as trouble in school. Who wouldn’t give up income for greater safety?

Perhaps if the mission of the police were radically redefined – from harassing people of color in ways that made it clear to them that they were neither welcome nor safe in non-black neighborhoods, to protecting black citizens so that they were safe in all neighborhoods, then people would consider moving to white neighborhoods without the push from Moving to Opportunity.

Today, many working-class black neighborhoods are characterized by long periods of calm and moments of acute crisis: everything goes smoothly until the foreclosure crisis, a hurricane, job loss, or a recession throws things into uncertainty.

If government does less to protect African American residents than others, during a crisis are African American families more vulnerable in a largely white neighborhood, or in a largely black neighborhood?

Distinctly high rates of residential segregation testify to African Americans’ collective conclusion that, no matter how considerable the differences and diversity among them, they are better off together.

The same has been true politically. The danger black people find in white neighborhoods comes both from neighbors and from the government, in the form of police who harass, schools that label children as problems, public services that seem to diminish as the proportion of white residents declines.

Politicians foster other racial problems too: the racialization of welfare recipients as black and their simultaneous vilification, the promotion of a racialized crime hysteria, voter disenfranchisement, and the scapegoating of people of color at every turn.

The racial hazards that people experience at the neighborhood level, then, are relentlessly renewed through our racially polarized politics.

Gregory Smithsimon is associate professor of sociology at Brooklyn College, City University of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. His book, “Cause … And How It Doesn’t Always Equal Effect” is out from Melville House