Down by Lake Osborne, deep in suburban Florida, there’s a stillness and solitude Mamudul Hasson has not experienced in years.

Among the damp grass, tall palms and gentle humidity the 21 year-old Rohingya refugee takes a seat, staring at the ducks and lapping water. It’s another world from what he left behind two weeks ago and he’s still in disbelief that he made it.

“It has been a very long time since I came to a place like this: quiet, easy,” he says. “It’s freedom. It’s the most important thing in life.”

Hasson had been among the hundreds of men held by the Australian government in a notorious detention centre on remote Manus Island in Papua New Guinea. Kept in limbo for over four years, he witnessed the murder of a fellow detainee and the untimely deaths of others. He slept in a tiny shipping container with four other men, used the putrid bathrooms every day, and experienced depression.

The indefinite detention was a consequence of a hardline immigration policy that sees asylum seekers arriving in Australia by boat automatically banished to offshore centres in Papua New Guinea or the tiny pacific island state of Nauru.

It was, in the words of Australia’s former chief immigration psychiatrist, deliberate torture.

In the final months of the Obama administration, the United States reached an agreement with Australia to resettle up to 1,200 men, women and children languishing in these centres. It was a deal that Donald Trump later branded “stupid” during a phone call with Australian prime minister Malcolm Turnbull.

“I hate taking these people. I guarantee you they are bad,” Trump said, suggesting, with no evidence, that some may become terrorists.

But despite threats to kill the deal, the administration has quietly admitted a handful of Australia’s refugees, about 200, since September of last year. It is likely the agreement will be discussed again on Friday when Turnbull visits the White House for the first time since the now-notorious phone call.

‘It’s all Australia’s fault’

Hasson is sitting less than 10 miles from Mar-a-Lago, Trump’s exclusive private members’ club now functioning as a frequent weekend presidential retreat.

He, like many others detained by Australia, was well aware of Trump’s slurs. And yet he holds no animosity for the president. Instead, he places the blame on Australia.

“We were kept in a place where nobody knew what was happening to us,” he says. “Even Donald Trump didn’t know. But it’s all Australia’s fault. It is their responsibility to show we are not terrorists – that we are just humans surviving, looking for a place we can live peacefully.”

Moving to America has meant more than just safety. It has given him a life.

Within days of arriving here, Mamudul signed up for adult learning classes. He hopes to earn a GED, the equivalent of a high-school diploma, before pursuing his dream of a career in IT. He was forced to abandon school aged 16, when he fled the military junta who have long persecuted the Rohingya Muslim minority in Myanmar.

He has been united with family he had never met before; a six year-old nephew and two uncles with whom he now shares a small bungalow. He speaks regularly to his mother, two sisters and brother, who are languishing in a refugee camp in Banglalesh after they were driven out of their village in Myanmar following the latest crackdown on the Rohingya last year.

He started playing soccer with a local team and caught a live match of his beloved Real Madrid on television for the first time since 2012. He tried Mexican food (and enjoyed it). He sleeps for six hours at night on a double mattress – double the daily rest he had on Manus, where crippling anxiety plagued him from the moment he arrived. He laughs more often.

“It is like a hand has pulled me out of the ocean to save me from drowning,” he says.

‘I saw only jungle, nothing else’

Like many refugees, Mamudul remembers in forensic detail the epic journey it took to get here.

He left his village of Maungdaw in Rakhine state in August 2012 after hearing he was wanted for questioning by the military. He fled to Bangladesh and then to Malaysia on a 10-day boat trip, where water and food ran out after six days and dozens of people died on the voyage. Their bodies were tossed into the ocean.

He was held by armed people smugglers for a month in Malaysia, with the threat of being sold into slavery if he could not a pay ransom. Eventually, with assistance from his family, he paid to be smuggled to Australia, taking a boat from Java in Indonesia to the Australian territory of Christmas Island.

He arrived on 20 October 2013, completely unaware, he says, that the country was now sending asylum seekers to detention camps in Papua New Guinea.

Five days later he was transferred to Manus. He remembers a wrenching in his gut as he landed: “I saw only jungle, nothing else.”

For more than four years he languished there with no end in sight. His lowest points came when an Afghan roommate, suffering severe depression, slashed his wrists in their cramped room, spilling pools of blood onto the metal floor. Then, in 2015, just days after his 19th birthday, he found out his father, a school teacher, had died – succumbing to injuries after he was beaten by the military back in Myanmar.

“He was my inspiration in life,” Mamudul says, trying to maintain a smile. “It was so tough.”

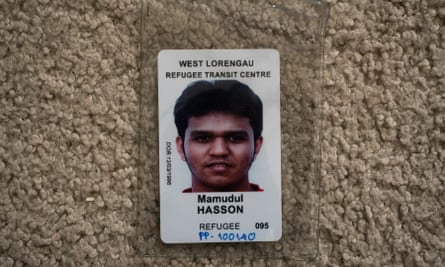

He brought only fragments of his time on Manus with him to America. His notes from English class, his detention centre ID card, and a bright yellow T-shirt and a pair of stonewashed jeans – neither of which he has ever worn in a bid to preserve them and to remind him of his father who bought them as gifts before he fled.

“This place gave me so much pain. I could never forget it,” he says. He still dreams of detention every night.

About 1,800 of Australia’s asylum seekers and refugees remain on Manus Island and Nauru. Advocates complain that the US resettlement program has been slow to process and vet refugees, amid Trump’s own crackdown on refugees and travelers from certain Muslim-majority countries.

Mamudul remains in contact with many of his friends still in limbo there. He fails to understand why he has been allowed to leave but other refugees have stayed behind. The guilt plagues him.

“Every day I just think about what will happen if Trump’s mind changes. They will be left behind and if they are left behind no-one knows what will happen to them,” he says.

“They have been suffering more than me.”