- India

- International

When a river recedes

With a water crisis looming, Gujarat will soon stop supplying Narmada waters for irrigation. For farmers who depend on the canals that bring water to their fields, that’s bad news.

Large tracts of land which were previously submerged have emerged in Antras village

Large tracts of land which were previously submerged have emerged in Antras village

(Express Photos by Javed Raja and Bhupendra Rana)

“The soil is flaky, not a good sign,” says Bhawansinh Chauhan, sitting on his haunches in his paddy field that lies along the Fatehwadi canal in Goraj village, in Gujarat’s Ahmedabad district. The crop is now nearly a metre high, but Chauhan is worried that if the government goes ahead with its “threat” and stops supplying Narmada water to the canal, his entire crop will be ruined.

“I had taken a loan of Rs 9 lakh to sow paddy on my 80 bighas and another loan to buy a tractor. If my crop fails, I will have no option but to sell my land,” says Chauhan, 55.

On January 12, long before summer set in, the Gujarat government issued an advertisement saying it would stop supplying Narmada waters to irrigate summer crops, and advised farmers not to sow them.

The reason: a crisis in the Narmada river basin this water year (July 1, 2017 to June 30, 2018). As a result, Gujarat, which usually gets 9 Million Acre Feet (MAF) from the Narmada river valley annually, has got about 45 per cent less.

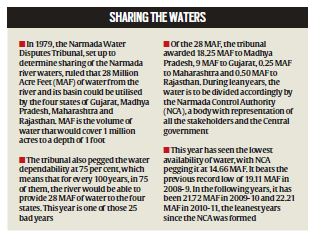

According to the Narmada Water Disputes Tribunal’s final award in 1979, 28 MAF of water from the Narmada river basin can be utilised by the partner states of Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Maharashtra and Rajasthan every year. This year, however, the Narmada Control Authority, a body set up by the tribunal to manage waters, declared that only 14.66 MAF would be available, a decision made on the basis of rainfall in the months of July, August and September. Gujarat’s share of 4.71 MAF is its lowest ever.

A temple and other structures are now visible.

A temple and other structures are now visible.

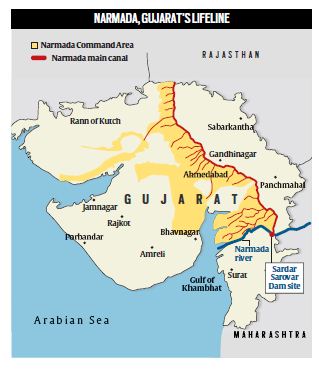

Narmada, Gujarat’s lifeline

Narmada, Gujarat’s lifelineAccording to a senior officer in the state-owned Sardar Sarovar Narmada Nigam Ltd’s (SSNNL) Canals Department, only 0.03 MAF of that 4.71 MAF remains for distribution. And the reservoir level is down to a dangerously low 107.1 metres — too low for water to be diverted to the canals.

Farmers in the 18.45-lakh-hectare Narmada Command Area, where the canal network is mandated to take water under the project, are worried. And angry. They accuse the state government of going back on its election promise and say the announcement came too late; many of them had already sown their summer crops.

As on February 26, 2018, over 1.41 lakh hectares in the command area had standing summer crops. The March 15 deadline hangs ominously over these parts.

Barely months ago, after the radial gates were installed on the Sardar Sarovar Dam, its height went up to 138.68 metres, from the earlier 121.92 metres, increasing the storage in the reservoir by an additional 1.48 MAF.

That should have been good news for the farmers of Gujarat; instead, the water scarcity has meant that the government had to stop supplying Narmada water for irrigation to the districts of Surendranagar, Botad, Morbi and Ahmedabad from February 15, a month ahead of the deadline. Another announcement followed, saying drinking water from Narmada would be provided till July 31.

Though on request from the Gujarat government, Rajasthan and Maharashtra parted with their share of Narmada waters, Madhya Pradesh turned down the request, citing rain deficit in the Narmada basin area.

As an emergency measure, on February 20, the Gujarat government began drawing dead water— water in the reservoir that cannot be drained using the dam’s outlets and can only be pumped out — from the Sardar Sarovar dam through the Irrigation By Pass Tunnel (IBPT). IBPT is a component of the dam which was not part of the original project, but was included after the then government headed by Keshubhai Patel moved a proposal to facilitate supply of the dam’s ‘dead water’ to the canals during emergency. Since it was constructed in 2000-1, IBPT has never been used to provide drinking water to Gujarat except on trial. But this year, say SSNNL sources, around 0.3 MAF ‘dead water’ has already been drawn from the dam.

Sharing the waters

Sharing the watersSo how did this crisis come about?

According to the Gujarat government, it is the result of poor rainfall in the catchment areas of the Narmada, around 97 per cent of which falls in Madhya Pradesh. In 2017, Madhya Pradesh received 27.69 per cent less than the average rainfall.

Besides, say SSNNL officials, the state’s increased dependence on the Narmada is a factor too. M B Joshi, General Manager of the SSNNL’s Technical & Coordination Department, says, “We were earlier not as dependent (on the Narmada) as the canal network was not completed. Today, due to the wide canal network (over 50,000 km), the reach of the Narmada water has increased.”

According to the SSNNL, 10,000 villages and 167 urban centres of Gujarat depend on the Narmada for their drinking water.

Critics, however, blame the government for not using the water judiciously, even accusing it of diverting water to the Sabarmati riverfront, considered a showpiece of the state government. The 11.5-kilometre-long riverfront needs an estimated 1 crore cubic metre of water and a part of this is fed by the Narmada. The water from the riverfront is further diverted to farmers in villages downstream the Sabarmati.

On March 4, the government stopped releasing water to the Sarbarmati riverfront, only to restart it a day later after farmers near Sanand, 25 km downstream from the riverfront, protested.

Chauhan, the farmer who owns 80 bighas in Goraj village, was among those who protested. “For over 15 years, the government has been supplying Narmada water to this region by diverting water from the Sabarmati riverfront. Before the elections, BJP leaders had assured us that the supply would not be disrupted and even asked us to go ahead and plant paddy on our fields. How can they now say they will stop water by March 15?” says Chauhan.

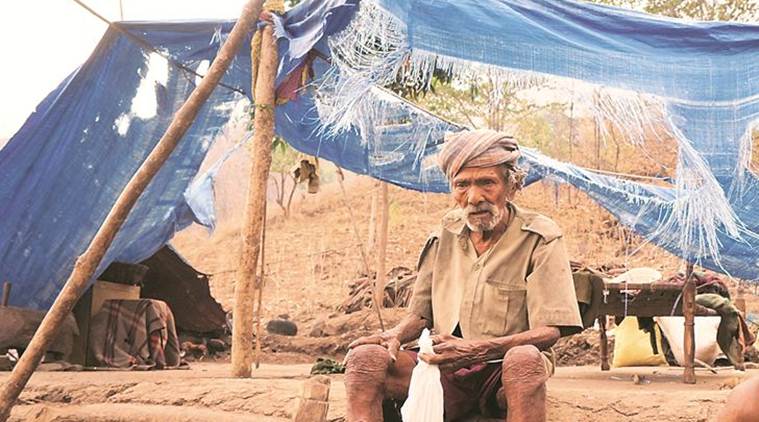

Dulji Rubya Bhil’s old house is still under water

Dulji Rubya Bhil’s old house is still under water

Y K Alagh, who was executive vice chairman of the Narmada Planning Group that made the Sardar Sarovar Development Plan in the 1980s, says the government shouldn’t have released water for the riverfront this year. “Gujarat is a water-scarce state and Narmada is its only major water source. In such a situation, every single drop of water should have been used effectively,” he says.

The government has responded by saying that the water has been used judiciously, with Chief Minister Vijay Rupani telling The Sunday Express, “This year, owing to less water in the Narmada catchment areas, we have got only around 50 per cent of our usual share. These allegations, that we didn’t use water properly, are all baseless. We have not used a single drop of water more than what we used last year. In fact, by increasing the dam height, we could store more water in the dam this year. We will answer any question related to Narmada in the Assembly.”

“We have made proper arrangements to make sure that the entire Gujarat gets enough drinking water till July 31. And we are committed to providing Narmada water for irrigation till March 15,” he added.

Workers at Kevadia, where the Sardar Sarovar Dam stands

Workers at Kevadia, where the Sardar Sarovar Dam stands

Writing in the government’s fortnightly mouthpiece Gujarat, SSNNL officer Joshi says, “It’s a fact that this year we have got less water. But, in addition to that, it will be a big mistake to believe Narmada as an unlimited and perennial source. And therefore, it is the need of the hour to explore more alternatives of water management, to develop more water storage, and to reuse old ‘water temples’ like wells and step-wells, to prevent elements who waste water and to optimise use of every single drop of water.”

CM Rupani agrees. “Yes, we are highly dependent on Narmada. But, what to do? In Saurashtra, there is no other source (of water),” he says.

Jatin Patel, 42, is “not very worried” about the March 15 deadline. His three-acre field lies along the Narmada Main Canal, which takes water all the way to Rajasthan, a non-riparian state whose share of 0.50 MAF cannot be turned off, according to the tribunal’s order.

So Patel knows his “perennial source of water” will never run dry. “The March 15 deadline will affect only those farmers who have their farms near smaller canals, where the flow of water will be regulated. All of us living near the main canal can continue to draw water illegally,” he says, confidently.

Patel has just arrived at his field, riding a motorcycle with a five-litre, yellow carboy filled with diesel fastened to its side. He soon pours the diesel into a running pump that is drawing water from the main canal.

In the absence of sub-canals to bring water from the canal to their fields, farmers such as Patel have for years been drawing water illegally. All along the main canal are PVC pipes that snake their way into the canal, from which water is pumped out.

As he supervises the labourers on his farm, Patel says, “I harvested cotton and, a month ago, planted jowar on my three acres. I will need water till April to irrigate my summer crop. Whatever the government says, I have a debt of over Rs 3 lakh and mouths to feed. I will continue to steal water from the canal. I am not worried about this March 15 deadline.”

(With inputs from Ritu Sharma)

Best of Express

Buzzing Now

Apr 18: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05