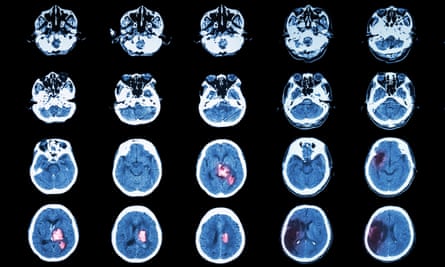

Ten years ago, Barbara Ehrenreich read an article in Scientific American that shook her to the core. Its argument was that the body’s immune system, far from protecting us, can enable the growth and spread of tumours, “which is like saying that the fire department is indeed staffed by arsonists”. In the 1960s, Ehrenreich had worked on immune cells as a PhD student, specifically on those known as “macrophages”, and had come to think of them as friends – frontline defenders against microbial invaders. Now that they stood exposed as traitors, one of her basic beliefs was shattered. If our body can attack itself, why bother trying to look after it? What’s the point in striving to stay healthy, when longevity is beyond our control?

“Old age isn’t a battle,” she says, quoting Philip Roth, “old age is a massacre.” In the past few years, she has given up on screenings and scans. Not that she is lazy or suicidal. But at 76, she considers herself old enough to die. All the self-help books aimed at her age group tell her otherwise; they talk of “active ageing”, “productive ageing”, “anti-ageing”, even “reverse-ageing”, with a long life promised to anyone who makes an effort, regardless of factors such as genetics or poverty. But to her, ageing is “an accumulation of disabilities”, which no amount of physical activity or rigorous self-denial can prevent. If she has symptoms, she’ll have them investigated. But when a doctor tells her there could be an undetected problem of some kind, she won’t play along.

Experience has taught her that standard health checks are at best invasive and at worst a scam. Overdiagnosis has become an epidemic. Bone density scans, dental x-rays, mammograms, colonoscopies, CT scans: she questions them all. Preventive medical care, in the US at least, has become a lucrative industry. Many doctors profit financially from the tests and procedures they recommend. And celebrity-driven campaigns for more screening increase the demand. People are being made sick in the pursuit of wellness. An estimated 70-80% of thyroid cancer surgeries performed on American, Italian and French women in the first decade of this century are now judged to have been unnecessary, she claims. And then there are all the elderly who “end up tethered by cables and tubes to an ICU bed”, their life needlessly prolonged and demeaned.

There’s an argument that health checks have value as rituals, that beeping machines in sterile rooms provide the kind of reassurance to modern western consumers that shamanistic drumming and animal horns do in more “primitive” cultures. Ehrenreich quotes from a 1950s spoof anthropology paper, Body Rituals Among the Nacirema (“American” spelled backwards), in which supplicants lie on hard beds within temples, while magic wands are inserted in their mouths and needles jabbed in their flesh. Modern medicine invokes science in its defence. But whereas science is “evidence-based”, medicine tends to be “eminence-based”, with patients in thrall to the doctor’s superior prestige. It’s no coincidence, Ehrenreich thinks, that most American medical schools still insist on the dissection of cadavers. That’s how living patients are expected to be – as passive and silent as corpses.

Ehrenreich’s scepticism about the medical profession is informed by her feminism and dates back to a moment in late pregnancy when she asked the male obstetrician who had just removed his speculum from her vagina whether her cervix was beginning to dilate: “Where did a nice girl like this learn to talk like that?” he said to the nurse standing nearby. That kind of misogyny may be on the wane but it hasn’t gone away. Women are still needlessly forced into humiliating positions by men in white coats. Gynaecological examinations “enact a ritual of domination and submission”, with the patient made to undress and be open to penetration, much as in the criminal justice system, “with its compulsive strip searches”.

Deprived of agency in her encounters with the medical profession, Ehrenreich found an alternative by taking up physical exercise, which offers greater promise of control. Initially mortified by the feebleness of her body, she developed a scary competitiveness and graduated from a women-only gym to a unisex version, where at her zenith she would outdo young men and “draw spectators for my leg presses at 270 pounds and lunges while holding a 20-pound weight in each hand”. She still works out, but no longer sees gym-going as a means of empowerment. Large businesses once notorious for exposing their workers to unhealthy conditions now promote corporate wellness programmes. But the benefits are dubious (their coercive nature may even be a source of workplace stress) and the idea that if you’re less than fit you’re less than human is pernicious.

Ehrenreich has fun at the expense of health sages and fitness gurus, with their mantras about the “wisdom of the body”. It would be unfair to describe her as gleeful when she lists some noted casualties – among them Apple co-founder Steve Jobs (who died at 56), US social activist Jerry Rubin (56), The Complete Book of Running author Jim Fixx (52) and the author of the book Younger Next Year: Live Strong, Fit and Sexy – Until You’re 80 and Beyond, Henry S Lodge (58). Still, she can’t resist wryly concluding: “If this trend were to continue, everyone who participated in the fitness culture – as well as everyone who sat it out – will at some point be dead.” That we’ll all be dead, sooner or later, is no longer indisputable. Death-deniers are a growing body; the richer the individual (invariably a man), the more hubristic their claim to immortality, whether it’s Russian billionaire Dmitry Itskov with his plans to surpass Methuselah by living to 10,000 or Larry Ellison, co-founder of Oracle, who finds mortality “incomprehensible” (“Death makes me very angry”). The diseases of old age used to be seen not just as inevitable but as kindly, even altruistic. Now they’re regarded as cruel, abnormal and, according to one expert (the author of Younger Next Year), “an outrage”.

“Every cell is on your side,” goes the holistic slogan, but Ehrenreich disproves it. Against the utopian presumption that our cells work in harmony, “like citizens of a benign dictatorship” or a smoothly running machine, she presents the body as a site of constant conflict and deadly combat, with cells pitted against each other as well as against external invaders. Those seeming good guys, the macrophages, turn out to be cheerleaders for death, encouraging cancer cells to do their worst. Philosophically, she concedes, it’s hard to imagine immune cells being accomplices in destruction; some scientists still dispute it and she owns up to “simplifying to an extent that would annoy many cellular immunologists”. But she makes the case persuasively, with 20 pages of notes and citations to back her up.

More controversially, she sees cells acting as though with a mind of their own – not following instructions but doing as they please. “Cellular decision-making” is the term for it, though you could also call it “free will”. Not that cells possess consciousness, but they are capable of acting in ways that are neither predetermined nor random, with an outcome of inflammation and disease. It’s a pessimistic scenario but at the end of the book Ehrenreich offers a glimmer of light. For such agency to exist at a microscopic level in our bodies points to a universe swarming with activity – and to mysteries beyond our ken. To recognise that, and see oneself humbly as a transient cell in a larger animistic order of being, makes the prospect of death easier to accept.

Or so Ehrenreich concludes. After her earlier sendup of New Age platitudes, this quasi-Buddhist celebration of non-selfhood sounds less than convincing. As does her recommendation of psilocybin (the active ingredient in magic mushrooms) as a way to abolish the self and approach death with equanimity: by taking a trip on a psychedelic drug, you’ll appreciate the beauty of the universe and go more gently into that good night. Really? Might you not be keener to stick around? And more resentful of the world going on without you? Like most polemicists, Ehrenreich is more persuasive when on the attack than when it comes to offering solutions.

There is a lot in her book to take issue with: the impatient dismissal of mindfulness, for instance, and the paranoid interpretation of the anti-smoking lobby as “a war against the working class”. Even her essential premise is flawed: yes, death can come even to those who have worked hard at staying healthy, but that’s a given and doesn’t mean it’s not worth the effort. And then there’s her animus against gyms, as the locus of a pampered, narcissistic, middle-class elite, when she continues to attend one. Still, she is one of our great iconoclasts, lucid, thought-provoking and instructive, never more so than here. That PhD in cellular immunology, left behind while she went on to write books and run campaigns, has proved useful after all.

- Natural Causes by Barbara Ehrenreich (Granta, £16.99). To order a copy for £14.44 go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only. Phone orders min. p&p of £1.99.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion