Sumitra Devi (45) went to sleep on the night of July 29 without any inkling that the water level in the Yamuna had risen. The next morning, Devi and others in Bela village on the Yamuna floodplains woke up to knee-deep water in their hutments. She knew it was that time of the year again.

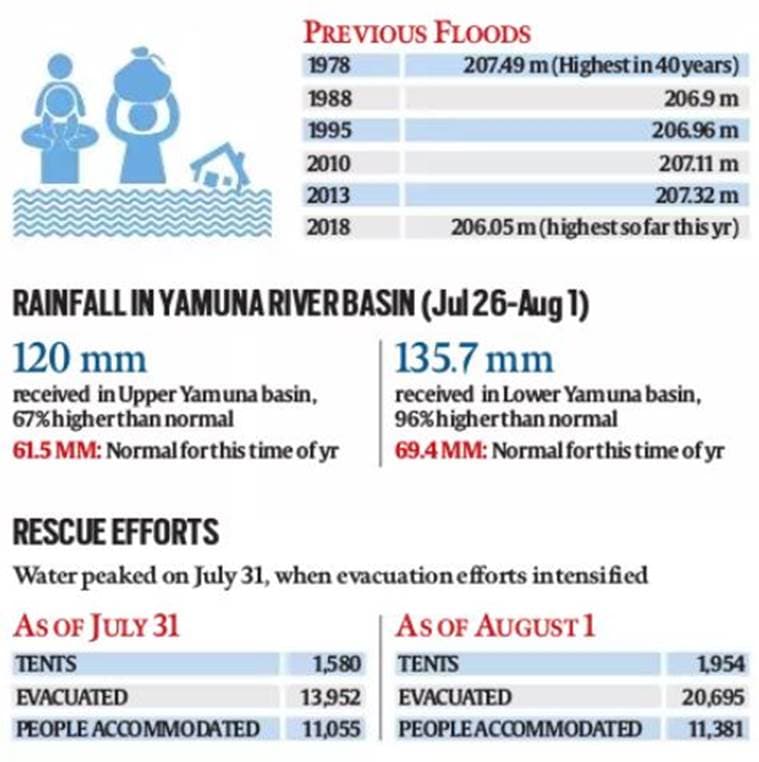

Around 6 am on July 30, the water level at the Loha Pul, used to assess how much the Yamuna had swelled, was at 205.62 metres — well past the danger mark of 204.83 metres. An evacuation process would soon follow, with over 800 people from the village being moved to makeshift tents. The same drill would be followed across six districts in Delhi to evacuate about 20,000 people.

At the hutment where Devi stayed with her children and grandchildren were an iron box full of clothes, important documents such as Aadhaar and voter ID, some utensils, a wooden bed, gas and stove. There was also the school bag of her youngest daughter, 11-year-old Aasha Kumari.

But most of the belongings were hurriedly placed on top of the bed, and the family grabbed only a few clothes and water bottles before heading to their tent across the Ring Road, near ISBT Kashmere Gate, around 6 km away. Devi said Aasha pleaded with her to let her go back and fetch the bag. But with the water level creeping up, returning immediately was not an option.

Vijay Rani and her family have resettled into their thatched hutment on the Yamuna riverbed, after the flood water receded over the past three days. (Express Photo by Tashi Tobgyal)

Vijay Rani and her family have resettled into their thatched hutment on the Yamuna riverbed, after the flood water receded over the past three days. (Express Photo by Tashi Tobgyal)

The process was not unfamiliar to Devi’s family, who had done it last year, too. But for her, personally, this was a year of immense loss. On Monday afternoon, as Devi was busy getting food from the authorities, Aasha and some other children went to the edge of the floodplain. The girl slipped and drowned in a pond dug up by authorities as part of beautification work, but now full of water.

“Bacha dooba, bacha dooba,” was all Devi heard. It was only when divers recovered the body that she realised it was her daughter. “She pleaded with me to let her go to school. I told her I would wash her school dress before that, and stopped her from going,” Devi said. Her nine-year-old grandson, too, fell into the water but was saved in time and is now admitted to a government hospital.

Sitting outside her tent on Saturday afternoon, Devi can only talk about her daughter: “She would write names of family members in English… during last year’s floods, she helped get our jhuggi in shape.”

She also regrets not paying heed to the authorities’ call to evacuate the floodplains on July 28. “They have set up health camps, we got food, water and toilet facilities, which we don’t have in the fields… But what good is all that now… They kept asking us to move to higher ground, but we didn’t until the flood came.”

At a relief camp (Express Photo by Tashi Tobgyal)

At a relief camp (Express Photo by Tashi Tobgyal)

In anticipation of the river swelling, the Delhi Boat Club, which comes under east district administration, had been doing rounds of river areas near Tronica City, Sonia Vihar, Geeta Colony, ITO East End, Haathi Ghat, DND, Batla House, Kalindi Kunj and Jaitpur, telling people it was time to move.

But many shifted to the makeshift tents only when water entered their jhuggis. There were many forced evacuations, with the task cut out for authorities: moving 20,000 people on the floodplains and adjoining areas — without inconveniencing the capital.

A SINGULAR FOCUS

At 6.30 pm on July 28, Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal called a meeting at his camp office to review preparations of flood control and management — following a third warning about discharge of 5,03,935 cusecs of water from Hathni Kund Barrage in Sonipat because of continuous rainfall, the highest since 2013.

District Magistrate (Shahdara) K Mahesh, who is also the DM of east and northeast districts, informed the CM that motorboats were stationed at 23 locations, along with first “responders” for rescue operations.

To ensure all agencies were on the same page, the CM directed MCDs, discoms, PWD, DJB, health and power departments as well as police to depute one representative each to the flood control room.“He emphasised that well-coordinated, all-out efforts have to be made to ensure timely evacuation of inhabitants from low-lying and vulnerable areas, and adequate provision of tented accommodation and food for the affected persons,” read the minutes of the meeting.

Day by day, the water level rose. By July 30, it had reached 205.62 metres. According to records, the Central Flood Forecasting division of the Central Water Commission, which monitors discharge from Hathni Kund, predicted it would take 36-72 hours for the released water to reach Delhi, depending on “prevailing flow conditions”. It was a race against time.

One of the first crises that authorities faced was when 12 people, including seven children, were stuck in a field near Burari Cremation Ground as water reached about 3.5 feet. An SOS went out to the Boat Club, and the in-charge, Harish Kumar, rushed along with four divers. “We managed to pull them out in time,” he said, crediting the success to placing boats at strategic locations.

But on Sunday, four teenagers drowned in the Yamuna near Alipur. They had allegedly gone for a swim. While two bodies were found, Kumar said strong currents thwarted efforts in finding the other two bodies.

ALSO READ | Swimming amid rapid current, four students drown in Yamuna

HOMES APART

To ensure coordination, District Magistrate Mahesh had also formed a group on WhatsApp with senior officers from various agencies. One of the first messages on the group: “Two officers are hereby directed to report to the office of DM East for duty in the flood control room.” Another message betrayed the sense of urgency: “A boy has drowned. Vehicle from PCR Sonia Vihar has already gone to attend the call.” Later, it was found that a man had drowned in Usmanpur.

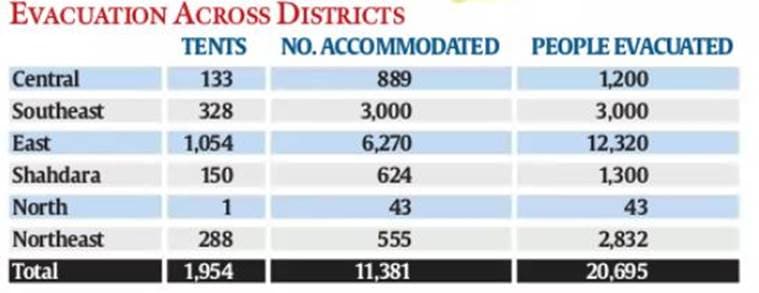

Officials were also acutely aware of what it takes to move such a large population in such a short time. In Delhi, the Yamuna crosses six districts — east, Shahdara, northeast, north, central and southeast — and spots were identified in each to set up relief camps.

One came up at Loha Pul, under the charge of SDM Rajesh Choudhary. Over three days, he had to set up 150 tents, and force people to leave their hutments and move to higher ground. “About 700 people were relocated under my sub-division. Initially, they did not want to come because they feared their belongings will be stolen. But that’s a law-and-order issue… authorities have to assure people that their belongings will be safe,” he said.

At her tent at Thokar number 21 on August 1, Vijay Rani said the facilities were “very good”. From the main road next to the Loha Pul, she kept a close watch on her hutments, her cattle tied to a pole nearby. The first day she was moved, authorities had made arrangements in a park, but she refused to budge.

“We needed to keep watch on our belongings and we made a makeshift tarpaulin tent on the main road. It was only the next day that we got a tent,” she said, adding that it was ironic how they got to avail facilities like drinking water, toilets, free food, electricity and mosquito sprays only when a crisis struck. During the rest of the year, getting drinking water requires a 1 km walk; electricity is drawn illegally from Loha Pul; and open defecation is the norm.

At another cluster of tents, people had to live without electricity for an entire night, forcing SDM Choudhary to take up the matter with higher authorities. “There is always a danger of snakes coming into tents,” he said, adding that at one point, a miscreant left a snake in the food van set up by an NGO. “Thankfully, the snake didn’t get into the food. We alerted local police,” he said.

Additional District Magistrate Ajay Kumar, who looks after east and Shahdara, was among those on the ground during the entire operation. He warned of another problem: Curious visitors. “A lot of people come to the banks to see the water rise. Many try to bathe, and that poses a huge challenge for us,” he said.

Then there were the expected bureaucratic hiccups. “BSES officials asked us to submit an application before installing a temporary meter. We faced the problem in at least two areas — Vivek Vihar and Preet Vihar. During a crisis, one cannot wait for an application to provide services. But the matter was later resolved,” he said. A BSES official, too, said the issue was “sorted out”.

B L Diwakar, assistant engineer of DUSIB, said 164 toilet seats were set up in trans-Yamuna areas in mobile toilet vans or in portable toilets. “We were there round-the-clock and made the seats available based on demand. We disposed the excreta either in sewers or soak pits, which was challenging .”

RETURNING, REBUILDING

By 8 pm on August 2, the water level had receded below the danger mark to 204.20 metres. Vijay Rani and her family had moved back with their belongings to their jhuggis. There was muck everywhere. She and her family got busy reshaping their jhuggis. They wiped the floor, made new mud stoves and put tarpaulin polythene on top of their huts. A sack of wheat grain had started to rot and had to be thrown out; a motorbike lying near the entrance wouldn’t start; and the children’s books were soaked and needed to be replaced.

As the sun rose on Saturday morning, Rani’s family was still waiting for the land to dry. “We lost all our crops… a loss of at least Rs 10,000. If the sun god is merciful, the land will dry soon. Every year, a similar devastation occurs, but this year reminded us of 2013, when the water level was very high. And like every year, we find ourselves at square one,” she said.

Sumitra Devi, on the other hand, has little will to rebuild her life or her jhuggi, where “sadness awaits me”. She says, resigned: “Every year, we triumphed over the devastation, but this year, I lost.”