- India

- International

What does the recent SC judgment on Aadhaar mean for people in Nandurbar?

Much before the Supreme Court started hearing a clutch of petitions challenging the Constitutional validity of Aadhaar and much before the unique identity number roiled a nation over concerns of privacy, Nandurbar had made peace with the 12-digit identification number.

Jaura Vasave with her six-month-old child. She decided to give up her maternity benefit of Rs 5,000 after failing to get an Aadhaar card. (Express photo by Prashant Nadkar)

Jaura Vasave with her six-month-old child. She decided to give up her maternity benefit of Rs 5,000 after failing to get an Aadhaar card. (Express photo by Prashant Nadkar)

Since the launch of the unique ID in this Maharashtra district, the 12-digit identity has been inextricably tied to people’s lives — from a mother without Aadhaar who was denied a maternity benefit to a child who is out of school, to officials who say it has streamlined benefits. What does the recent Supreme Court judgment mean for their lives?

Aadhaar nahin, toh niradhaar (Without Aadhaar, there is no foundation),” says Raju Narayan Thakre, father of Tembhli village sarpanch Azad Thakre.

Much before the Supreme Court started hearing a clutch of petitions challenging the Constitutional validity of Aadhaar and much before the unique identity number roiled a nation over concerns of privacy, Nandurbar had made peace with the 12-digit identification number.

Read | The no more Bangladeshis

Click to enlarge

Click to enlargeHere in Nandurbar, a district in north-west Maharashtra that’s often counted among the most backward in the country, life continues to often come up against the Aadhaar test — at PDS shops, at the post office, in banks, schools and hospitals.

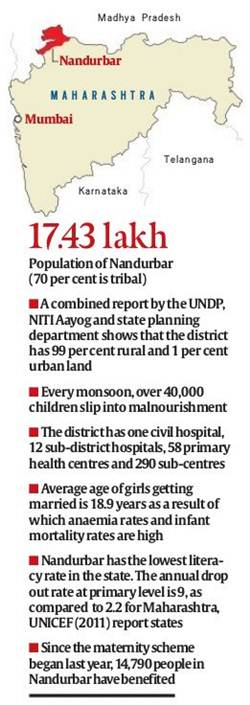

After all, Nandurbar was Aadhaar’s launch pad. It was here, in a small village of 1,600 people in Tembhli, that then prime minister Manmohan Singh and Congress president Sonia Gandhi handed out the first Aadhaar cards. That was 2010. Since then, according to data from the district collector’s office, 98.5 per cent of the district’s projected population of 17.43 lakh has got an Aadhaar.

On September 26, the Supreme Court, while upholding the Constitutional validity of the Aadhaar Act, upheld the linking of Aadhaar to allow people to avail of subsidies and benefits provided by the government, but struck down the requirement of linking the unique ID to bank accounts and mobile phone numbers or insisting on it for pension and school admissions.

With television a rare commodity in Nandurbar and literacy levels at a low 64 per cent (according to the 2011 Census), Collector Mallinath Kalshetty says the judgment will take time to reach villages deep inside the district. “Once the state government conveys (the order) to us, each department will sensitise people. We will follow the honourable Supreme Court’s order,” he says.

******

On the ground in Nandurbar, Aadhaar has worked in varying ways — to both include and exclude people, to empower and to delegitimise.

Maternity scheme

Some 15 km from Taloda town, down a mud road, is Jeevan Nagar, a village set up in 2003 for the rehabilitation of a thousand-odd villagers affected by the Sardar Sarovar dam project. The village of over 110 mud-splattered huts has electric poles, but is yet to be fully electrified.

Under a white LED bulb, with flies fluttering around, Jaura Vasave, 27, cradles six-month old Pratiksha, her first-born. She shares the house with 11 other people, two charpoys, a few trunks and a goat. Three men in the family do labour work, earning Rs 100 each a day.

At the mention of Aadhaar, she murmurs, “We don’t have money for that.”

Express Opinion | Across the Aisle: Good Aadhaar, Bad Aadhaar

Without Aadhaar, Jaura hasn’t got the Rs 5,000 that women are entitled to for their first delivery, under the Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana, a maternity scheme that aims to provide nutrition to women and their new-borns.

Jaura says it was a local nurse who told her about the scheme three months ago. The nurse also told Jaura she would need a bank account to get the money. But when she went to a Taloda co-operative bank, the officials told her she would need Aadhaar to start a bank account. Then, she says, her husband Ranya, 25, skipped his day’s work, borrowed money from villagers and the couple made two trips to the Aadhaar centre in Taloda. Each trip, says Jaura, cost them Rs 400.

People continue to queue up at the Aadhaar centre in Shahada. (Express photo by Prashant Nadkar)

People continue to queue up at the Aadhaar centre in Shahada. (Express photo by Prashant Nadkar)

“The first time we went, there was no electricity for the biometrics, the second time, the finger printing failed because there was an injury on my hand,” Jaura laughs. “Aur kitni baar jaun, paise nahin hai ab (How many times do I go, there is no money left).”

Jayesh Khairnar, District Project Officer (DPO) of the Department of Information and Technology in Nandurbar, admits there have been glitches in the enrolment process. “The software version was changed by the UIDAI (Unique Identification Authority of India) and that led to technical issues. The new software had to be reinstalled and that took days,” he says.

Also Read | SC aadhaar ruling: Police to capture biometrics of illegal migrants to track them, says MHA

But Jaura and her husband say they have given up. “We tried collecting money to visit the agent a third time but couldn’t get enough. So we decided we don’t want Aadhaar or the Rs 5,000,” says Ranya.

It was in Tembhli village in Nandurbar that Manmohan Singh and Sonia Gandhi handed out the first Aadhaar cards in 2010. (Express photo by Prashant Nadkar)

It was in Tembhli village in Nandurbar that Manmohan Singh and Sonia Gandhi handed out the first Aadhaar cards in 2010. (Express photo by Prashant Nadkar)

But there are happy stories too. Like the one Orsing Gurji, a social worker in Nandurbar, shares about Kamlabai Gulabsingh Pavara, a 27-year-old young mother. Gurji says Kamlabai had no idea of Aadhaar. She enrolled for it only because others in her village were doing so. After she delivered her third child, the local primary health centre asked for her Aadhaar. Days later, Rs 4,000 was deposited into her account under the Manav Vikas Yojana, a state government scheme that compensates women for wages lost during pregnancy.

“She went by herself to the bank to withdraw money and used it to buy clothes for her baby, wheat and rice. That was the first time Kamlabai had ever entered a bank,” says Gurji.

Also Read | Surveillance after the Aadhaar judgment: What Internet freedom?

Dr Raghunath Bhoe, civil surgeon at the Nandurbar district hospital, is optimistic that “hiccups around Aadhaar” will ease over time. “Aadhaar will ensure there is no duplication. Because biometrics are necessary, only the beneficiary can withdraw money from the bank. Earlier, we had several cases of husbands misusing their wives’ maternity benefit funds,” he says.

But Bhoe is most excited about a hidden potential of Aadhaar: that it will some day help trace missing children. “We conduct their biometrics at birth and then again when they are five. This data will help trace any child who goes missing,” he says.

Pension scheme

Naganbai Sonawane is a beneficiary of the Indira Gandhi National Old Age Pension Scheme. Every month, the 69-year-old tribal from Tembhli village visits a bank, 2 km from her home, to withdraw the Rs 600 that gets deposited in her bank account under the scheme. Every month, the bank official thrusts the small, hand-held machine in her direction and asks her to press her finger. Every month, her biometric scan fails.

“Haath ki rekhayein mit gayin umar ke saath (Fingerprints have changed with age),” says Naganbai, who lives alone in Tembhli; her son is a labourer in Gujarat.

In Tembhli, Ishwar Patil, a local social worker, laughs at the mention of OTP. (Express photo by Prashant Nadkar)

In Tembhli, Ishwar Patil, a local social worker, laughs at the mention of OTP. (Express photo by Prashant Nadkar)

Admitting to problems of validation because of fading fingerprints, DPO Khairnar says villagers have been asked to update their fingerprint data every five years. “We have also kept a body lotion in the enrolment centres. We advise tribals to apply lotion on their hands so that there is no dust and the machine can scan the fingerprints.”

Officials say there are ways to get round the problem of failing validations. Even if the biometric scan fails, they say, a one-time-password (OTP) is sent to the beneficiary’s mobile phone, which can be used for validation.

In Tembhli, Ishwar Patil, a local social worker, laughs at the mention of OTP. “When bank officials told people that their Aadhaar could be validated through OTP, some of them went to buy cellphone SIMs. But the shopkeeper told them they would need an Aadhaar and a biometric scan to get a SIM card. So they returned empty-handed,” he says.

School admissions

Eight-year-old Harish Pavara spends most of his time at his grandfather’s five-acre farm in Wadi rehabilitation village, picking and cleaning cotton. With his Aadhaar still “under process”, he has already lost two years of school.

He wants to learn English. “And become a sainik,” he smiles, eyeing his younger brother Amrut’s notebook. Amrut studies in a local tribal school and their younger sister goes to a private school in Aurangabad, where Harish is now seeking admission.

After Harish’s father Natwar Pavara died of sickle cell disease in 2016, his mother Pintibai remarried, leaving Harish and his three siblings in the care of their grandfather.

“His father wanted him to study English. Under a tribal department scheme, children can apply to English-medium schools and their education is free if their name gets picked in a lottery. But to fill the form, the child needs an Aadhaar,” says Harish’s uncle Kantilal.

The family made multiple visits to Taloda town to get an Aadhaar for Harish, the first over two years ago. The biometric and iris scans got done without a fuss and they were told the Aadhaar number would reach them by post. The post never reached.

The lowest enrolment is in Toranmal, a valley inaccessible due to lack of road networks, where only 51 per cent children have Aadhaar. (Express photo by Prashant Nadkar)

The lowest enrolment is in Toranmal, a valley inaccessible due to lack of road networks, where only 51 per cent children have Aadhaar. (Express photo by Prashant Nadkar)

“Every time we visit the office in Taloda, they say the post office has sent it,” rues grandfather Jamsingh Pavara.

He says he tried to get Harish enrolled in a local tribal school and even toyed with the idea of enrolling Harish in a government orphanage in Taloda, “but at both places, they insisted on an Aadhaar card”.

When told about the Supreme Court verdict and how Aadhaar wasn’t required for school admissions anymore, Pavara looks puzzled. “What is that all about?” he asks, the furrows on his forehead deepening.

Rajendra Kamble, education officer for primary schools in Nandurbar, says that while “Aadhaar isn’t mandatory for admission, it is required for children to avail of mid-day meals or scholarships in school. Aadhaar also helps in ensuring that children don’t take admission in more than one school to seek multiple monetary benefits”.

Collector Kalshetty says “immediate steps” will be taken to direct schools to clear admissions of children stuck due to Aadhaar. “We will spread information on the Supreme Court verdict through newspapers,” he says.

After the Maharashtra Women and Child Development Department directed all anganwadis in April to update the Aadhaar details of children eligible for nutrition schemes, data shows that of 1.53 lakh children below six years in Nandurbar, Aadhaar cards were made for 73 per cent. The lowest enrolment is in Toranmal, a valley inaccessible due to lack of road networks, where only 51 per cent children have Aadhaar.

“But we don’t deny food to any child even if they don’t have Aadhaar,” says Suman Panpatil, an anganwadi worker in Tembhli.

Enrolment for Aadhaar starts early. In Tembhli’s zilla parishad school, for instance, students who enter Class 1 are enrolled immediately. Thirty of 41 children who took admission in Class 1 this year already have Aadhaar. “Books and uniform can come later, Aadhaar is more important,” says teacher N H Kohli.

Data, however, shows that even with Aadhaar, approvals often get stuck in bureaucratic tangles. In 2016-17, the Tembhli zilla parishad school applied for 178 scholarships under the tribal department’s Suvarna Mahotsavi Scholarship scheme that provides Rs 1,000 to each child per year. Kohli says they made it a point to submit the Aadhaar details for each of the 178 children. In two years, not all students have got the scholarship money, says Kohli.

******

Yet, in Nandurbar, Aadhaar lives on.

The government Aadhaar centre in Shahada, a town close to Tembhli, sees over 50 visitors every day. “Half of them come for correcting the details on their card,” says Mahendra Bhavsar, who is poring over certificates as a queue snakes out in front of him.

A few metres away, Sunil Koli, 25, sits with his six-month-old infant in his arms. His wife Jayshree has been standing in the queue to get her surname corrected — from Nigam to Koli.

“We went several times to the Mandana centre, which is hardly 3 km from our village. But there, sometimes the biometric machine wouldn’t be working, sometimes there is no electricity,” says Sunil.

So on Thursday, he skipped his daily labour work and the couple travelled 15 km to the Shahada centre. Sunil says he spent

Rs 80 on travel and paid Rs 150 to the desk officer to update his wife’s Aadhaar.

“We have been waiting for hours. I hope our work gets done today,” he says as the baby lets out a loud wail.

Jayshree is now in the queue for an iris scan. If she gets her Aadhaar corrected, she will be eligible for the Rs 5,000 benefit under the maternity scheme.

Behind Jayashree in the queue is Suman Salunkhe, 55, from Lonkheda village. She clutches an Aaadhar card that is blank where her date of birth should have been. “I need to update this card and get these entries filled because I have to join a self-help group. And before that, I need Aadhaar,” says the 55-year-old.

At his office in Nandurbar town, Collector Kalshetty too is clear about his goals: Starting October 1, the administration will hold Aadhaar camps in schools, primary health centres and anganwadis in the district’s most isolated pockets. “We have to ensure 100 per cent Aadhaar coverage in Nandurbar,” he says.

Apr 19: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05