In 1963, when Joe “Cargo” Valachi, a Genovese family soldier who became the infamous “first rat,” told a Senate subcommittee that the organization he called Cosa Nostra was actually real — not the old-wives’ tale that America’s top cop J. Edgar Hoover had made it out to be for more than four decades — a vast trove of secret history came to light.

As it turned out, those rumors were true. The U.S. government had knowingly done business with the Sicilian Mafia when the Roosevelt administration hired Lucky Luciano to watch the docks during World War II. The so-called Valachi papers, reconfigured by Francis Ford Coppola’s Godfather movies and The Sopranos television show, supplied the lingua franca of that now bygone mob saga. You didn’t have to be a made man to know to take the cannoli and leave the gun.

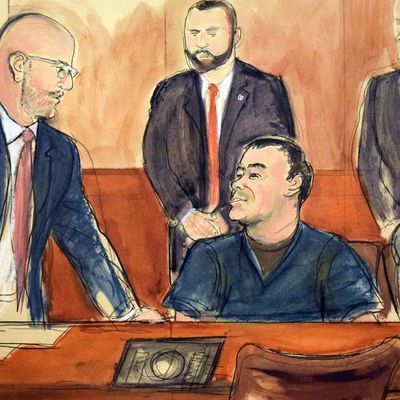

In that way, Jesus “El Rey” Zambada, one of the prosecution’s star witnesses in the ongoing case against drug trafficker Joaquin Guzman Loera, a.k.a. El Chapo, found himself cast in Valachi’s rat/public-explainer role for a whole other gangster era. The U.S. Attorney’s office, anxious to explain the complexity of their case against the Mexican drug lord to the jury of working-class Brooklynites, had installed El Rey as the keeper of the narco record.

It was a good choice. As the brother of El Chapo’s longtime partner, Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada García, El Rey had been there from the beginning, telling the jury how he abandoned a career as an accountant to join Chapo and Mayo in what eventually became the fearsome Sinaloa cartel. El Rey was in the thick of it, running the Mexico City “plaza” for the cartel, which meant he was in charge of spreading around the money in the highest circles, until he was imprisoned in 2008. It was clear Zambada had been heavily coached by the Feds to deliver the “right” answers to their metronomic questions. And yet El Rey sometimes went a little off script.

Asked by the assistant U.S. Attorney where he was currently residing, El Rey, sporting dark-tinted glasses and a raconteur’s suit jacket that did little to obscure the orange jumpsuit beneath, said, “You know, jail.” Asked for how long, the witness threw up his hands and said, “Vida, life.” Asked how he got the name El Rey, Zambada said, “When I was born, I was the youngest, el ultimo, of the family. They named me Jesus. My father said, ‘Here he is, the King of the World … the Rey.’ So I have been El Rey since that moment.”

It wasn’t that Zambada was breaking any news. The El Chapo template is already pretty much set in stone: son of an impoverished gomero, a former sicario, he was the leader of the biggest, most violent narco cartel of all time. What Zambada’s commentary brought to the table was a discerning eyewitness selection of detail, a storyteller’s art. It was there in the scenario-setting of El Rey’s account of Chapo’s 1992 attack on Tijuana cartel rivals at the Christine Night Club in Puerto Vallarta. There was special élan in Zambada’s telling of Chapo’s classic 2001 escape from Puente Grande prison in a laundry cart. El Rey recalled the gush of wind as Chapo’s getaway helicopter, arranged by El Mayo, landed along a remote coastline. When Chapo came into view, everyone on the ground cheered. “We had done this and we were happy,” El Rey said with a still-amazed pride. “We were so happy.”

As Zambada told that story, a small smile crossed the face of El Chapo. Through the earlier testimony Chapo — who doesn’t speak English — had seemed to zone out. They’d fixed him up with an earpiece to hear the translation, but it was uncomfortable, so the defendant chose to rest it on the table in front of him. Now however, he was rapt. Chapo and Rey had not seen each other since 2007, when they were both present at a meeting in the Sinaloa Mountains to plan the upcoming cartel war against fellow trafficker Arturo Beltyran Leyva, a conflict that would leave thousands dead. El Rey might have been a rat like Joe Valachi, but he was also a bard, a chronicler of glorious youth.

This was but one incident in what proved to be a topsy-turvy first week of testimony in the Chapo trial, which saw the daily arrival of the drug lord’s 29-year-old wife, Emma Coronel Aispuro. Coronel Aispuro, mother of Chapo’s twin daughters, sat there hour after hour as journalists scouted her numerous fashion choices, with news of her puce nail polish quick to appear in the Mexican tabloids.

That said, the week’s big story concerned the defense’s opening argument. Faced with a mountain of evidence and Chapo’s own partially self-created legend, New York–based defense attorney Jeffrey Lichtman, best known for representing John Gotti Jr., decided to go full Trump. Rather than a kingpin, Lichtman contended Guzman was little more than a flunky, some Fredo figure with “barely a second-grade education,” incapable of leading a global organization like the Sinaloa cartel.

The real leader of the group, Lichtman said, was El Rey’s brother, El Mayo, who remained at large, Lichtman contended, because he had paid “hundreds of millions” in bribes, a ladder of corruption that went “all the way to the top,” including the Mexican presidents Felipe Calderón and Enrique Peña-Nieto. These accusations immediately set off an international controversy, prompting angry denials from both Calderón and Peña-Nieto. Outraged, the U.S. Attorney’s office claimed Lichtman’s commentary to be “permeated with improper argument, unnoticed affirmative defenses and inadmissible hearsay.” The entire thing should be struck from the record, the prosecution told Judge Brian Cogan.

Cogan declined to do this but assailed Lichtman in open court, saying, “Your opening statement handed out a promissory note that your case is not going to cash.” Yet, however far-fetched, Lichtman’s strategy — the Times dutifully referred to as a “conspiracy theory” — might be the best option they’ve got. El Chapo as the small-timer “fall guy,” set up with the complicity of federal agencies like the DEA and FBI, is an argument that just might find traction with a Brooklyn jury.