Rochester 10

[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Who makes Rochester Rochester?

The people who are most often in the public eye are the elected officials, corporate leaders, university presidents and researchers, and entertainment figures. But thousands of Rochesterians make equally important contributions to the life and fabric of the community, often unknown to all but a few people.

Again this year, we highlight the work of 10 outstanding Rochesterians, people whose efforts, talent, and determination make Rochester the community it is. A musician whose side interest is entertaining children… the creators of a safe, nurturing community place especially for black women… a husband and wife dedicated to telling the stories of workers… a 19-year-old developing an app to further social change… an activist speaking out for the needs of the homeless…

You’ll find these stories and more in our 2018 Rochester 10 feature.

IRSHAD ALTHEIMER - Public Safety By Tim Louis Macaulso

Irshad Altheimer was a gunshot victim when he was a young man. Now he studies gun violence: what triggers it, the impact it's having on city neighborhoods, and how to stop it. Altheimer is the director of the Center for Public Safety Initiatives at the Rochester Institute of Technology. In that position, he conducts and oversees research at the Center to help law enforcement agencies around the country with their budget priorities and the programs they use.

"Our interest is in bringing the data and analysis to the forefront of decisions about criminal justice practices," Altheimer says. "We want to encourage our law enforcement and community partners to embrace evidence-based practices and also to evaluate their own programs."

Drug prevention programs like D.A.R.E. and the crime-prevention programs aimed at teens like boot camp attract publicity, but research shows they're not effective tools, Altheimer says.

"If you want to stop gun violence in a community but you don't know how or why it occurs," he says, "how can you address it?"

Altheimer is black, has a thick dark beard, and is active in Rochester's Muslim community, and he says he realizes some people in law enforcement aren't used to seeing someone who looks like him give them advice on how to be more effective. "In academia, there aren't many African-Americans in criminology," he says.

But, he says, his interactions with the Center's law enforcement partners are positive.

The goal of the Center and its research is to improve public safety, and some significant barriers need to be addressed, he says.

"Crime is a real problem," Altheimer says. "I don't ever want to minimize that. But I think our dialogue about crime is often manipulated for political reasons. Crime becomes a proxy for race."

If you don't think so, he says, take a look at the way white-collar crime is treated in the US. "A white guy who goes into work and steals $30,000 from the company probably won't serve much time, if any at all," he says, "but a young black male without a weapon steals something from a corner store and spends time in prison." The young black man is seen as a threat to society, he says.

And, he says: "Go downtown to the courts. It's pretty bad optics. Almost all the people working there are white, and the majority of people being served are people of color."

The media play a huge role in the public's perceptions about crime, he says. It's not unusual to hear people say they won't go downtown in Rochester because of a story they saw on TV, he says.

"Crime is not evenly distributed," Altheimer says. "There are whole city neighborhoods that haven't experienced a shooting in years, and some never have." But even in neighborhoods where there has been some violent crime, most people do not engage in it, nor are they victims of it, Altheimer notes.

"There's a very dangerous tendency to think that some whole cities are becoming dangerous places," he says.

Altheimer grew up in Tacoma, Washington, a predominantly white city. He went to Alabama State because he wanted to go to a historically black college, earned his doctorate in 2005 at age 28, and joined RIT in 2012.

The crack epidemic was a defining moment for his generation growing up in the 1980's, he says. And, he says, there's a stark contrast in the way black people who were caught using crack were treated and the empathy shown to white people who are addicted to opioids today.

There have been times when he has struggled in his work with those types of contrasts, Altheimer says: "There's been a lot of soul-searching."

And he's been challenged by people of color concerning his work with police, even though the data he can provide helps officers make better decisions.

"I never got the whole sell-out thing," he says. "A lot of the people I grew up with and know what I'm doing think it's great."

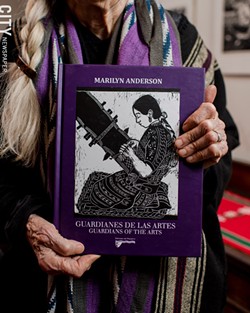

JON GARLOCK AND MARILYN ANDERSON - Labor

BY ANDREA HICKERSON

Married for 43 years, labor historian Jon Garlock and artist Marilyn Anderson work in solidarity and for solidarity. They have collaborated on books, photo exhibits, and even coloring books, promoting the contributions of workers in Rochester and Guatemala. Their robust body of work underscores the relationships between craft, oppression, and resilience.

"There are a lot of ways to tell people about workers," Anderson, a 1970 RIT graduate, says.

Originally a painter, Anderson has concentrated her work on Mayan textiles. In the 1970s, she and Garlock visited more than 40 locations in Guatemala while she documented weaving techniques and took portraits of craftswomen.

"I try to make people recognize the beauty of the work and the experience of it," she says.

The couple later returned to interview and photograph Guatemalan refugees displaced by civil war who were living in Mexico. The result was the book "Granddaughters of the Corn: Portraits of Guatemalan Women," published in 1988, which juxtaposes Anderson's portraits of Mayan women with documentation of the war and crimes perpetrated against the women, written by Garlock.

Since then, Anderson has produced creative works in drawings, linoleum prints, and woodcuts. Some of them are displayed alongside a group of essays in her 2016 book "Guatemala/ Guardians of the Arts: Prints of Guatemalan Artists." The book was published in English and Spanish by a women-run press in Guatemala.

Indeed, a true distinction of both Anderson and Garlock's work is that they are dedicated to circulating it within the communities that inspire them instead of prioritizing a larger, mass market appeal. This way, they practice solidarity with the communities whose movements they document.

Garlock earned his PhD in history at the University of Rochester in 1974 under the mentorship of celebrated labor and slavery scholar Herbert Gutman. Rather than teaching, however, he wrote grants at Monroe Community College, and he continues to produce educational literature and to participate in local labor organizing.

Garlock has been an executive board member of the Rochester Labor Council since 1987, and he helped revive Rochester's Labor Day parade in the 1986, a tradition that had stopped in the 1920s. Around the same time, he began co-curating the Labor Film Series at the Eastman Museum's Dryden Theater. Its 30th anniversary season kicks off next fall. Overall, the series has screened 300 films, but Garlock estimates he has reviewed 800 or more during the selection process.

When he began curating the series, he says, just over a dozen film buffs would attend. Last year the series averaged an audience of 160 people per film. A screening of "North Country," a 2005 film about the landmark 1984 sexual harassment case Jenson vs. Eveleth Mines, starring Charlize Theron, drew around 300 people.

Although labor and manufacturing are less relatable to many Rochestarians since Kodak's demise, Garlock says the #MeToo movement likely inspired this large audience. He says he hopes, however, that the movie educated more people about sexual harassment and blue-collar labor. "Most people think of sexual harassment as white-collar work," Garlock says. "This is a different story. These women don't have access to the same resources."

And, he says, angst about national politics has likely triggered a renewed interest in labor and film. "Our working theory is that people are so agitated and upset they need to see these films together," Garlock said. "They need to be together in a public space."

It might also help that interest in socialism is having a revival. "Socialism is becoming, if not respectable, at least reasonable," he says.

A popular saying from the 1960's was "If you don't know, learn. If you know, teach," Garlock notes, and he and Anderson remain committed to both. They have ideas for future collaborations in the Rochester community and with each other, perhaps something graphical.

"There is no end in solidarity work to be done," Garlock said. And, he says, "You are never too old to make art or engage in solidarity work."

JAMISON CLARK - Design and Activism

BY DANIEL J. KUSHNER

Jamison Clark – chief design officer of Goose Design Co. and creator of a prospective "app for activism" called "Updraft" – has always been precocious. By the time he was 12, he was dreaming of creating a school for activism that would include hands-on training in how to bring about social change. Now 19 years old, Clark has already begun to realize his vision for fueling activism, propelled by "design thinking."

Clark co-founded Goose Design with Isabelle Bartter (now chief executive officer and chief technology officer) to provide photography, videography, and other design work for socially conscious businesses. Goose seeks out local companies that focus on ethical practices and community building, and its clients have included Leep Foods, Eat Me Ice Cream, and Holistic Herbals.

When he considers who to take on as a client, he considers a business's motivation, Clark says. "'Especially with companies that are ethical and looking to make an impact," he says, "there's usually a really deep 'why,' of like, 'Oh, I want to feed people, get more access to food,' or 'I want to help reduce poverty. I want to provide jobs in this way or have an environmental impact or change the way food is produced.'"

In particular, Clark wants Goose Design to work with for-profit businesses certified as "B Corps" because the certification identifies them as having a positive impact on their community and society – helping the environment, for example. "We're really interested in working with B corps," Clark says, "because they go through a rigorous testing process, and they have to be retested every two years."

His plan is that the focus on improved business practices will also be applied in the development of existing non-profit projects. And this is where Goose Design Co.'s flagship project, "Updraft," comes in. The app is an example of design and technology converging to promote community activism. If it's successful, it could become a game changer in how individuals, businesses, and organizations communicate and work together for the greater social good.

Clark has been designing the app for the past several years, hoping to create something that will help individual organizations and people collaborate on activist work. The work will fall under categories such as human rights, food justice, shelter, and environmentalism, with projects that could include things like urban agriculture, homeless services, and refugee settlement. A successful Kiva campaign earlier this year resulted in a loan of $5,000, and now Goose can develop the Updraft prototype, with the goal of an eventual beta release of the app. The company is currently seeking investments to continue the work.

The story behind the name "Goose" and its Updraft app offers insight into Clark's personality and aspirations. At some point, people started calling him "Goose," but what began as an affectionate nickname took on greater meaning for Clark. "I learned about how geese uplift each other with their updraft from their wings," he says. "So when they're in a 'V' formation, the updraft from the wings helps the other geese to fly more efficiently." Essentially, the goose became Clark's spirit animal.

Clark says he has always been sensitive to differences in cultures and to the problem of prejudice. "So I always knew that whatever I wanted to do, it had to be for a purpose," he says.

Clark grew up with a wide range of interests, including the performing arts, food, and physics. He attended Brighton High School as well as a school in Vermont and graduated early at the age of 16. He then began working with Small World Foods and learning about organic foods and fermentation, before starting Goose Design Co. in 2017.

"When I discovered that design wasn't just graphics – 'cause I thought it was for a lot of my life – and that it was actually a process that you could apply to different things using different skills, and this whole idea of design thinking: my world totally changed," Clark says.

STEPHANIE WOODWARD - Disability Rights

BY JEREMY MOULE

Stephanie Woodward says it's impossible for her to separate her work from the rest of her life.

Woodward is director of advocacy for the Center for Disability Rights. And as a wheelchair user, much of what she deals with in her daily work also affects her personally.

So if she goes out to dinner somewhere and she uses the bathroom, she'll probably assess how accessible it is. If she hears someone say the R word, "I am now lecturing them for the next 10 minutes about how about how that's offensive and should be taken out of their vocabulary, just like any other highly offensive words," she says.

Disabled people have to be constantly vigilant about their rights, Woodward says, because too often they're not only disregarded, but they're expected to be happy with what they've got. They have to fight to get restaurants to provide both accessible entrances and bathrooms, to get accessible housing, and to stay in the communities where they live.

"Often times, disabled people are told to be quiet or expected to be quiet and are certainly not expected to be feisty or push back," Woodward says. "So I'm not exactly what people would expect. And I'm OK with that, because being quiet isn't saving lives."

As advocacy director for CDR, Woodward works on anything that ensures that disabled people can live in the community and have the same rights as everyone else, she says. And her days are rarely the same.

Sometimes she's trying to get a business to remove a step in front of its entrance, so wheelchair users can get in and out. Other times, she works with other CDR staff on local, state, and national policies. Currently, the organization is working with City of Rochester officials on new guidelines that would require any new one- or two-family homes built with city funds to meet basic accessibility requirements.

"I like to say I make or break laws in the name of disability rights, depending on the day," Woodward says.

She gained some national notoriety in 2017 when members of ADAPT, a national disability rights group, protested Congressional Republicans' efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act and slash $800 billion from Medicaid.

During a protest outside of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell's office, Capitol police began arresting demonstrators, of which Woodward was one. As police pulled her out of her wheelchair and carried her off, protesters and media captured the scene on camera. The footage spread fast, and news organizations initially treated it as an unsettling spectacle, though some did ultimately explore the issues at the center of the protest.

For Woodward, the experience was nothing new; it was her 16th arrest at that point, and it wasn't the first – or last – time she was carried away. The next week, in Columbus, Ohio, police grabbed her by the wrist and ripped her out of her wheelchair. Then she was screamed at for not getting into a police car, even though her wheelchair was still in the building she was removed from, she says.

"It was a normal experience for me," Woodward says, "and I thought it was so interesting that the world fixated on what the police were doing to me and not on what the government was trying to do to millions of disabled Americans."

The Medicaid cuts would have meant that more disabled people would have gone into nursing homes or other institutions instead living independently in their own communities. Not only is serving people in their own homes and communities cheaper, Woodward says, but it's better for individuals and society.

The repeal attempt failed, though Congress did ultimately pass less-severe Medicaid cuts.

Woodward lives in Greece, and this summer, she began entering road races. She's pushed the Rochester 5k, the Rochester Half-Marathon, the Jungle Jog, and recently a 15k. Her boyfriend, a former Paralympian in wheelchair racing, got her started and helped her train for the races.

"I'm more of a pizza roll with the cats on the couch, and he's like kale and exercise," she says. "That was my mistake for dating a healthy person."

TONYA NOEL AND KRISTEN WALKER - Empowerment

BY JAMES BROWN

The August 2014 death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, hit black America like little else in recent memory. It was the latest in a string of police-involved deaths of unarmed African Americans, and the tension between black America and the police led to civil unrest in Missouri and galvanized protests around the country.

In Rochester, Tonya Noel joined a precursor of BLACK – Building Leadership and Community Knowledge – shortly after the events in Ferguson. She and dozens of others gathered, protested, and marched in the center of downtown Rochester south to the Ford Street bridge. That's when Noel noticed Kristen R. Walker with a mutual acquaintance. "Finally," she thought, "someone like me."

After the march, Walker and Noel realized that they ran in the same circles in activism and were both among the patrons at the old Tajze' Wine and R&B Lounge. The now-closed State Street bar was a focal point of much of their social scene. After nights out at Tajze's, Noel and mutual friends would have nightcaps at Walker's house in southwest Rochester. And the late nights fostered their budding friendship during what was a traumatic year culturally and personally.

Walker had suffered a miscarriage that year and lost a fallopian tube in the process. And Noel, a mother of two, acknowledged what her family and friends had known about her just about all her life: she was queer. Walker also identifies as queer today.

Too many people don't take the pain of black women seriously, Walker says, so she and Noel created Flower City Noire Collective. Its mission, they say, is to fill the "void of safe spaces" for black women in the community while elevating "women of color in their communities using a holistic approach" and "to organize with imagination, respect, and sisterhood." The group is intentionally multigenerational, to provide experiences for black women of all ages.

Walker and Noel lead service trips across the country as part of their mentorship of black teenage women 14 to 18. The trips are free for the young participants: cost is a sticking point for Walker and Noel, who want to give young women of color a chance to see beyond Rochester without burdening their families with travel or lodging costs.

Recently, the group went to Washington, DC, to attend the March for Black Women. And they went to Grafton, New York, to visit the black-woman-owned Soul Fire Farm, whose focus is ending racism and injustice in the food system. Soul Fire Farm's Leah Penniman is the author of the recently released book "Farming While Black," which advocates for black-owned rural and urban gardens.

Noel spearheads Flower City Noire Collective's urban farm in the Jefferson Avenue neighborhood. Tending the garden helps the group connect with their neighbors while teaching gardening to Flower City Noire Collective's members. Walker leads a bi-weekly book club featuring only black female authors, most recently Octavia Butler.

And the Flower City Noire Collective makes a point of being visible when violent crime hits southwest Rochester. They offer hugs and lend an ear to their community during tragedies.

"We're kind of like black hippies," Walker says with a Cheshire-cat grin.

Another project on the horizon for the collective is Harriet's House, a home in southwest Rochester once owned by a member of Walker's family. Harriet's House was named after legendary abolitionist Harriet Tubman. Walker and Noel envision the house as a community space and place of healing for black women.

Today, Harriet's House is more dream than reality. The house needs a new roof and many repairs. Walker and Noel expect to fund the work through donations and bartering and say all other operating revenue comes from making and selling buttons. Flower City Noire Collective's goal is to remain free of donations from large grant funders. Walker and Noel say they realize that making Harriet's House a reality will be expensive, and they are wrestling with whether they should turn Flower City Noire into a non-profit in the new year.

PENNY STERLING - LGBTQ Rights

BY ANDREA HICKERSON

Penny Sterling began acting as a man. A theater graduate of Ithaca College, she was named the "Funniest Man in Rochester" in 1992. Yet Sterling's external humor masked an inner turmoil. "I was angry all the time," she says. "I had a baseline of simmering anger that was barely contained."

In April 2014, Sterling began planning her suicide. Then one night she took a gender-identity quiz on the internet. It was revelatory.

"I was almost completely transgender," she says. Eighteen months later, at age 54, she came out. "I took an awful lot of people by surprise," she says.

Naturally, people – including her children – had questions. At first, Sterling turned back to stand-up to explain her new life, although this time she "wasn't sacrificing truth for laughs," she says.

After mainly performing at open mics, in 2016 she submitted her first play, "Spy in the House of Men: A One-woman Show with Balls," to the Rochester Fringe Festival. To her surprise, it was accepted, and she performed three shows. Since then she has performed her autobiographical play in Ithaca, Washington, DC, Cincinnati, and Minneapolis. She estimates that 1000 people have seen her perform.

"They identify with me," she says. "I touch a tricky subject and go over it in a personal way that isn't preachy or maudlin. I don't play the victim. It is my life, and I don't take anything away."

It takes her a few moments to regroup after each performance, she says, because the experience of performing and reliving the ups and downs of her past is so emotionally draining. Yet Sterling often concludes her performances with a "talk back," where the audience can ask questions.

"This is helpful to so many people," she says. "It is immensely gratifying." Sterling struggles with her faith, yet she says she says performing about the transgender experience has become her ministry.

Despite first-hand experience of harassment based on her appearance, she says she thinks that being a taller, more mature woman protects her from some of the more extreme discrimination faced by younger, transgender people.

"There only so many damns I have to give anymore," she says.

And Sterling is eager to share her experience in support of the transgender community. When the Rochester Business Journal published an offensive syndicated cartoon negatively depicting a transgender person, Sterling wrote an open letter to the RBJ that she posted on her Facebook page.

"This cartoon gives power and cover to the people who would rather see me dead than joyful," she wrote. "And you're okay with that."

To Sterling's surprise, the RBJ responded immediately and took her up on her offer of a special performance of "Spy in the House of Men." More than 75 people attended the performance at her church, Artisan Church. In November, the RBJ also featured Sterling in the first episode of its "BizCast," "Respecting Diversity."

In addition to advocating for transgender and other human rights, Sterling is involved in activism around homelessness, Planned Parenthood, and the Ugandan Water Project. She wants to be an ally for all minorities.

"When you marginalize, you hurt," she says.

Sterling has a day job in retail, but she aspires to work in theater full time. She performed with musicians Mike and Mel Muscarella of Violet Mary in a show called "Parents and Children, Husbands & Wives: It's all Relatives," at Geva Theatre at this year's Fringe Festival. She's also developing a show on parenting ("Children Are Designed to Be Raised by Idiots") and one on dating as a transgender woman ("SHMILF LIFE"). She says she's a much more nuanced performer now than when she was younger.

"I have more shades I can reveal," she says. "Before, I only had two crayons. Black was rage and white was joy. Now I have 64 colors, and I'm able to use them all."

MERCEDES PHALEN - Activism

BY JAMES BROWN

Mercedes Phalen has always been a rabble-rouser. She speaks sharply and chooses her words carefully. Her hair is dread-locked, and she wears a septum ring. Her oversized gray sweater, slumped down her shoulders, bears an image of someone painting an incomplete peace sign on a wall next to cursive words that spell "obey."

In many ways, the sweater encapsulates the quick-witted, politically minded Phalen. Her work is never done.

Phalen lives in Beechwood, a Rochester neighborhood she chose for its sense of comfort and community. Her father lives nearby, and many of her friends and acquaintances, all activists, live in Beechwood as well.

The 28-year-old single mother has spent most of her adult life caring for and working with children, including a stint with Action for a Better Community. As an activist, she's involved herself with cause after cause, formerly working with the local chapter of the National Organization for Women and with Metro Justice.

Currently, she's the lead organizer for the Rochester Chapter of Citizen Action of New York, a grassroots organization promoting progressive candidates and working on such issues as education, health care, poverty, racism, and campaign finance reform. She estimates that she spends 70 hours a week knocking on doors, planning events, speaking at events, and protesting.

Phalen says she doesn't seek the spotlight, but the spotlight found her last year when she was among the activists helping residents of the homeless encampment on Mt. Hope Avenue, on land owned by Spectrum and the Bivona Child Advocacy Center.

"People tend to act like people who are homeless are invisible," Phalen says. "When someone takes the time to hang out with them, it makes their whole day."

When residents of the encampment were threatened with eviction last April, Phelan joined other activists to sit in on the property for a week to prevent it. Phalen describes the experience as "humbling" and filled with "good energy and shitty weather."

The eviction date came and went, and the activists ended their sit-in. Days later, though, Phalen got a call. Spectrum employees were demanding that the residents leave. She rushed to the encampment, gave the employees a few choice words, and was arrested for trespassing.

In the months that followed, Mayor Lovely Warren and other local officials sat down with Phalen, residents of the encampment, and other housing activists, and by mid-summer, Warren announced a plan for a permanent encampment site near West Broad Street.

Phalen has mixed feelings about her arrest. "I'm glad that it happened," she says, "because it brought more attention to the situation, and I think that attention is part of what helped push for the permanent encampment."

"But I don't want to be considered the face of that particular group or movement," she says. "I strongly believe in those being directly impacted being the actual faces and actual sayers of what they want and what's happening."

For Phalen, the protest at the homeless encampment was a victory, she says, but the war is far from over.

"Someone asked me the other day, 'What are you going to do in five or 10 years?'" Phalen says. "I'm going to do this. It doesn't even feel like work to me. I would love to see a world where I'm not needed. I would love to see a time where there's nothing left for me to fight for."

SUSAN PORTER - Criminal Justice

BY TIM LOUIS MACALUSO

In 2013, it cost taxpayers an average of $60,000 to care for an inmate in New York State. And if the inmate was located in New York City, it cost three times that, according to the New York Times. Many states have taken steps to lower their prison population, and now the federal government maybe following suit, says the National Conference of State Legislators.

That means more people who are incarcerated are eventually released back into their communities, says Susan Porter, executive director of Judicial Process Commission. The non-profit, which was founded in 1972 by the Reverend Virginia Mackey and Lois Davis, is dedicated to helping ex-prisoners restart their lives. For instance, they provide mentoring and referrals for drug and alcohol counseling for people who have recently been released.

But re-entry into society has many barriers. Starting over, even for people who have been convicted of minor offenses, is extremely hard, says Porter, who has been helping people return home to Rochester for 36 years.

Porter earned her degree in natural sciences from the University of Michigan, but a short stint as a volunteer with a prisoner advocacy group in Pennsylvania caused her to change career paths. She learned immediately, she says, that the justice system is far from perfect.

"One of the first people I went to see showed me his glasses, which were broken," Porter says. Prisons are notoriously bad when it comes to inmates' eye care, she says, and the prisoner asked her to take his glasses and get them fixed. But that's a big violation, because in most cases, visitors can't take anything in or out of prison.

The justice system is hardest on poor people – frequently people of color – who can't afford a good attorney, she says.

"It's a disgrace that we have not addressed the racial issues associated with the criminal justice system," Porter says.

JPC was founded on a belief in redemption and rehabilitation rather than punishment for people who have been incarcerated. Last year, JPC's bare-bones staff of five served more than 700 people out of a small office it rents in Waring Baptist Church on Norton Street.

Research shows that about two-thirds of people who are released from prison commit crimes and return to prison within three years. But that's often because they returned to society with no education, skills, or support, Porter says. JPC's first goal is to help people stabilize their lives. For instance, one of JPC's programs involves finding permanent housing and then building on that stability.

"I have 25 families in the program right now," Porter says. "All of these people were homeless." Once the former prisoners have housing, JPC links them to other support services, which range from alcohol and drug treatment to education and job training.

But for people who have been convicted of a crime, regardless of whether it's a misdemeanor or a felony, the biggest obstacle is finding employment, Porter says.

"It's really, really difficult to get work," she says. "Most people want to work, but can't find it. In a way, you're disabled by your conviction."

A criminal record can't be expunged in New York, but in some instances JPC can help people get their records sealed. JPC also helps people obtain a Certificate of Relief of Disabilities or a Certificate of Good Conduct.

"Both certificates pull together evidence of rehabilitation to show that you are a changed person," Porter says. But in certain careers where state certification or licenses are required – health care and education, for instance – the documents may not help.

One of JPC's most important programs is mentoring people recently released from prison. Reducing recidivism is heavily dependent on someone helping people with things like dressing appropriately for a job interview, showing up on time, or avoiding a drug or alcohol relapse, she says.

Despite the frustration of working with a small budget and slow-moving bureaucracies, Porter says she still loves her job, even after three decades.

"I'm always so inspired by my clients," she says, "because they've overcome so much."

JON LEWIS - MUSIC AND EDUCATION

BY DANIEL J. KUSHNER

As a child, musician Jon Lewis wore a lot of different costumes from day to day, so much so that his neighbor frequently asked: "So who are you today, Jonny?" And for Lewis, now in his early 30's, some things haven't changed.

"You could ask me who am I today, and I might be a filmmaker, or I might be Mr. Loops, or I might be a serious folk songwriter," Lewis says. "I do still dress up in different costumes every day. So it's been a part of my life since forever. I think I needed to create something for that to continue in my life."

Lewis has plenty of creative outlets, from his work filming documentaries for the Ontario County Historical Society and animated music videos to his evening gigs as the frontman of the upbeat, highly melodic rock quintet simply called the Jon Lewis Band. But it's his role as the local children's entertainer Mr. Loops that has resonated most, in Rochester and elsewhere.

With no prior experience working with children, Lewis began his transformation into the goofy, kind-hearted Mr. Loops – complete with his signature, bright burgundy sports coat and fedora – after he began writing odd, nonsensical songs using a loop pedal and posting music videos online. His friends' children started calling him "Mr. Loops," and the parents suggested that he perform at birthday parties.

Lewis reluctantly tried out their idea, volunteering at day care centers and nursery schools. He initially resented Mr. Loops' popularity and ability to resonate with audiences, compared to that of his regular musical persona. But something had clicked. "To educate kids as well as entertain them became something that was really fascinating to me," Lewis says, "and I found out that I was really natural at it. Just my general personality is very 'Mr.Loops.' Sometimes, I'm pretending more to be Jon, and when I'm Mr. Loops, I can kinda let go."

Prior to launching Mr. Loops, Lewis had worked for 10 years as a high-end electronics salesman, but it was his three years of formal training as a comedy improviser in the Fairport High School group "Downstage" that helped prepare him for the world of kids' entertainment. He found that working with children meant needing to engage with them, being responsive, and changing the performance based on what was happening in the audience.

"Kids, especially at the 4-year-old level, I find it's pretty easy to maybe give them technology to keep them 'quiet,' or busy," Lewis says. "And I think that's really detrimental. So most of the time, if you can just engage with a kid, or give them some sort of creative motivation to do something, their brains start to fire off so much faster."

When he's playing music for adults, he says, the focus is on achieving healthy self-expression. Performing for younger audiences is different. "I wanna build something with kids, so when I do Mr. Loops, it's very interactive," he says. "I'm always focusing on how I'm building that relationship with the audience."

Mr. Loops' notoriety has also led to other opportunities. Lewis was invited to audition as host of the popular Nickelodeon show "Blue's Clues" last March, and although he didn't get the part, it helped him realize the value of making a difference in Rochester. In the fall, Lewis became a preschool teacher at Baden Street Settlement's Childhood Development Center, and he'd eventually like to become a school principal.

"Maybe there are six or seven new hosts of 'Blue's Clues' in my class," Lewis says. "Instead of just being the one guy, I can make a whole bunch of positive warriors."

RENAN SALGADO - Human Trafficking

BY JEREMY MOULE

Human trafficking is a massively complex issue. And when it comes to labor trafficking, there's a global web of causes and influences, including politics and government, industry, natural and man-made catastrophes, want of opportunity, and exploitation.

But at the root of it all is an insatiable desire for cheap labor, which underpins the economies of the United States and most other industrialized nations, says Renan Salgado, senior human trafficking specialist for Worker Justice Center of New York. The dynamic dates back to the beginning of time, when one group of people waged war against another and the loser basically became the labor force for the victor, he says. Later, it gave birth to the transatlantic slave trade.

Labor trafficking is present in a lot of industries, from hotels and restaurants to construction. Salgado tends to focus on trafficking in New York's agricultural industry. Workers there are filling jobs all around us, and we're desensitized, he says.

The workers are the victims in the equation, he says. They're often brought into the country through arrangements that resemble indentured servitude: paying someone to get them into the country and then having to work until they've paid off the debt. Agricultural workers coming from Mexico or Central America often owe between $7,000 and $15,000, Salgado says.

Their obligations leave them vulnerable to all kinds of abuses, from physical intimidation and threats against their families to wage theft, he says.

And the societal dehumanization or criminalization of the migrant workers only helps perpetuate their exploitation, Salgado says. Criminalizing and dehumanizing them sends a signal that it's OK to treat them poorly, he says. And that's a tactic that's been used over and over again with every ethnic group that's served as migrant workers for a particular era.

Chinese immigrants who came to the US to work on railroads were persecuted through the Chinese Exclusion Act, for example. Mexicans and Central Americans are the "latest flavor" in a long line of targeted workers, Salgado says. And this phenomenon isn't unique to the US, he says. In France, there's a similar dynamic with Algerians, he says.

Much of Salgado's work focuses on identifying victims of trafficking and helping them. He serves on regional law enforcement task forces that discuss how to handle trafficking in those areas. He works with attorneys to develop cases against traffickers and to help victims of labor trafficking. He also helps connect victims to service providers.

But lately, he's focusing a lot more on prevention efforts. He's interested in "catching migrations before they start," he says, and has been training government prosecutors, judges, and law enforcement in Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and the United States.

He's also eyeing the foodie movement, with its focus on how food is produced, distributed, and consumed. He wants consumers to be conscious of the labor aspect of food, too.

"There's a lot of attention being given in this new generation to nutrition," he says, "or, like, organic and sustainable, but not to the people that are working there."

Outside of his job with the Worker Justice Center, Salgado is a rapper who goes by the name SAI. He's been performing internationally for 10 years and initially became known for his socially conscious lyrics, which are mostly in Spanish.

Most of his fan base is in Mexico, and though he's from Ecuador and was raised in Brooklyn, his knowledge of Mexican history and current affairs – which he's gained partly through his job – allows him to rap about issues relevant to his listeners. One of his most popular tracks is "Militaras En Las Calles," translated as "Military in the Streets," which Salgado says talks about, as you might expect, "how crazy it is to see the military in the streets all the time over there."

He's now moved into a slightly more experimental, fun approach.

"I'm getting older," he says, "so I'm trying to have as much fun as possible before I leave this earth."