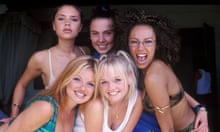

Salma has never even heard of the Spice Girls. Her life, hunched over a sewing machine for up to 16 hours a day, is a world away from the luxuries enjoyed by the millionaire pop band.

But while neither knows it, Salma and the Spice Girls are connected. The factory where she has worked for more than five years, off a narrow, winding road three hours’ drive from Dhaka, is where charity T-shirts designed by the group were made.

The £19.40 garments were produced on behalf of the Spice Girls and then sold to raise money for a Comic Relief campaign intended to “champion equality for women”, which pointed out how “women earn less”. It is a reality Salma knows only too well.

Perched on a chair in the tiny room she shares with her husband and seven-year-old son – barely more than 3.5 metres by 3.5 metres (12ft x 12ft) in size – she describes the harsh reality of her working life at the Interstoff Apparels factory.

Salma, whose name has been changed to protect her identity, speaks gently but vividly recounts the repeated injustices she and her colleagues face.

A small gas-burning stove on the floor in a small corridor is shared between four families. There is one toilet – a hole in the ground – and an overhead pipe without a shower head for washing.

Despite her modest surroundings, at 5,000 Bangladeshi taka (£46.30) a month, the rent eats up more than half her 9,080Tk salary, which includes an attendance bonus that she does not receive if she is sick.

ProfileFrom Gazipur to primetime TV: how the T-shirts are made

Show

• Machinists at the Interstoff factory in Gazipur stitch the garments together for about 35p an hour.

• The T-shirts are shipped to the Czech Republic, where another company prints the #IWannaBeASpiceGirl slogan.

• The Belgian brand Stanley/Stella, which oversees the production process, receives approximately €5 (£4.40) for each T-shirt from the US "crowdselling platform" Represent.

• The Spice Girls, who have announced that proceeds from the T-shirts will go to Comic Relief, appear on The Jonathan Ross Show in November, with the host proudly holding up one of the garments to the camera.

• Represent, which had been commissioned by the Spice Girls to get the T-shirts made, puts them on sale online for £19.40 each plus postage and packaging.

• Comic Relief said about £11.60 from the sale of each T-shirt was given to the charity.

Even with her husband’s income, the couple barely get by, with bills including their son’s school fees, food, electricity and medical expenses.

Other workers at Interstoff Apparels’ factory earn less, Salma said. Salaries are set by grades that depend on experience.

Pay is to rise this month as the government increases the minimum wage in the garment industry to 8,000Tk a month. It is the first rise in five years, but workers point out it does little for more experienced employees who already earn more. Salma is expecting a modest increase of a few hundred taka, but is unsure exactly what she will receive.

Workers at the factory are given “impossible” targets of sewing up to 2,000 garments a day, she said.

Speaking through a translator, Salma, who is in her mid-20s, explained: “Suppose someone is given a production target, but she couldn’t hit her goal. The chances are high that she’d get verbally scolded very badly. She might even get called inside the office of the production manager and get verbally abused.

“Inside the production manager’s office they use very bad, abusive language. Like, ‘This isn’t your father’s factory’, ‘The door is wide open, leave if you can’t meet the production goals’.

“Sometimes they use more obscene language like ‘khankir baccha’ (daughter of a prostitute), and many more that I can’t even say.

“Sometimes many female workers can’t bear the insults and pressure from the management, and they quit. Even last month, a few of my colleagues left because they faced very bad behaviour and they were shattered.”

Workers, including those who are pregnant, have to do overtime, she claimed. “Many workers don’t want to do the overtime, sometimes they even cry when the management make them do overtime forcefully. There was a worker I knew who was pregnant and she was forced to do night duty on top of her regular hours and overtime,” Salma said.

Q&AResponses to the Guardian's findings in full

Show

The Spice Girls are “deeply shocked and appalled” by the Guardian’s findings, according to a spokesman for the band, who said they found it “heartbreaking to hear about the treatment that these women receive”. The band had sought assurances from Represent, the online retailer that sold the T-shirts, that the garments would be ethically made, and said the manufacturer was changed without their knowledge.

The band pledged to personally fund an investigation into the factory’s working conditions and demanded Represent donate profits to “campaigns with the intention to end such injustices”.

A Comic Relief spokesman said the charity was “shocked and concerned” and had also checked the ethical sourcing credentials of the supplier, which was then changed without its knowledge. The charity was due to receive approximately £11.60 for each £19.40 T-shirt sold but had yet to be given any money, the spokesman added.

Represent said it would refund customers on request, calling the reported conditions at the factory “appalling and unacceptable”.

A spokesman said: “Represent has strict ethical sourcing standards for all of our manufacturers, and we had felt confident printing on blank shirts from Stanley/Stella for this campaign due to the brand’s strong reputation and leadership within the Fair Wear Foundation.

“To clarify, Comic Relief and Spice Girls did everything in their power to ensure ethical sourcing, and we take full responsibility for the choice of Stanley/Stella in this campaign, and confirm that this is something that we didn’t bring to the attention of Spice Girls or Comic Relief.”

The factory's co-owner Shahriar Alam, a Bangladeshi foreign affairs minister, said he did not think it was “right from a journalistic point of view to add my name to this story”. He admitted being a part-owner and co-founder of the company behind the factory, Interstoff, but said he resigned from the board five years ago.

Interstoff Apparels' director, Naimul Bashar Chowdhury, confirmed the factory produced blank T-shirts for Stanley/Stella. He said Alam was “a mere shareholder of the company” and was not involved in the management of the business.

He said the company would investigate the Guardian’s findings but also described them as “simply not true”, adding that Interstoff has a “zero-tolerance policy on harassment and use of any slangs or abusive language”. However, he admitted there had been “single incidents” in the “long past where verbal abuse have resulted to employee dismissal”.

He said no complaints had been received about excessive targets and the company adhered to the government’s legal minimum wages. It has a “participation committee” elected by workers to voice complaints, he said, adding that the factory is regularly audited.

“The living wage is a debatable and subjective issue; we for ourselves can say our basic pay is as per the local law and we have over that different performance-based financial incentives,” Chowdhury added.

He pointed out the company employs 80 disabled workers, staff are trained about harassment and abuse, and a medical centre at the factory provides healthcare. Pregnant workers are given monthly checkups, Chowdhury said.

Bruno Van Sieleghem, the sustainability manager at Stanley/Stella, said the brand was investigating the findings and “strongly committed to help this country and his workers to improve their welfare”. The Fair Wear Foundation, a organisation funded by brands that works to improve standards, audits Interstoff every three years, he said, adding that the company's team is “closely monitoring” FWF’s “corrective action plan”.

He said Stanley/Stella was aware that machinists at Interstoff work overtime until 9pm, but not that they stayed on until midnight. He said the brand had received no reports about employees complaining of harassment at the factory.

He said the brand, which received approximately €5 (£4.40) for each T-shirt, was committed to improving standards for garment workers in Bangladesh, but admitted it used factories in the country because they offer a “competitive price”. The T-shirts were printed by a company in the Czech Republic, Van Sieleghem added.

FWF said it inspected the factory in December, interviewing 30 workers off-site. The organisation said some “non-compliances” were discovered, but the interviews “did not reflect the allegations of harassment in the factory”. However, the foundation acknowledged that this “does not mean this did not happen”.

It described the hours at the factory as “excessive”, but FWF said it found workers are “free to refuse overtime”. It said it supported staff being paid a living wage.

“So she had to work from eight in the morning till midnight. She was crying all the time.

“One day she was throwing up and she repeatedly said she’s not feeling well. Still she was forced to work late. She left the job the next day because of that incident.

“It pains so much when we watch this kind of incidents, but there’s only so much we could do. We tried to talk to the supervisor, even offered any of us would fill in for her – just let her go. But the supervisor didn’t agree, he said, ‘No, she has to finish her shift’.”

Salma estimated she has to work overtime in the evenings for half the days in the month, sometimes until midnight. The intense work environment creates health problems for machinists.

“Fainting is pretty common,” she said. “Especially during the hot summer. Also, the huge workloads put a lot of pressure on the workers. Sometimes they just fall from their chairs. It happens every month.

“I think it is because of the workload and also they can’t sleep properly because they are working late, but also they have to come to the office in the morning. So they don’t get enough sleep in between. There are many workers with neck and back pain as well because they are always working on [the] same posture.

“There are air conditioners in the floor but it’s too many people. So it’s always hot.”

Recently, she said, she has started to have severe neck pain. “It is a huge trouble,” she said. “The doctor has shown me some exercises. But for that, I have to take at least a 10-minute break during my shift. If I take a break and when I return to my station, I see a huge number of products already piled up there.”

A spokesman for the band said they were “deeply shocked and appalled” by cases such as Salma’s and would personally fund an investigation into the factory’s working conditions. Comic Relief said the charity was “shocked and concerned”.

The online retailer that sold the T-shirts, Represent, said it took “full responsibility” for the situation, while Interstoff said the findings would be investigated but were “simply not true”.

Salma is not alone. Another machinist at the factory, a single mother of two who has worked there since 2013, told how she is forced to loan money from family and neighbours to survive.

She said she is paid 8,450Tk a month, including a 600Tk attendance bonus, for a 54-hour week including paid lunch breaks. It would take her more than a week to earn the £19.40 it cost to buy one of the Spice Girls T-shirts.

The wages barely cover her rent and the school fees for her 17-year-old daughter and younger sister. She recently had to borrow 20,000Tk from her brother for bills. Her ex-husband, who has a new family, provides no financial support.

The machinist, in her mid-30s, said she has no choice but to work overtime. In the most extreme cases, she and her colleagues stay on until midnight. “Recently the workload has gone down, but I had spent as long as 16 hours per day working in the factory on several occasions. And I lost count how many days I worked this long in the past six years, but the number would be huge,” she said.

Though she desperately needs the extra money, she also yearns for the freedom to be able to choose when she finishes.

Once, she cried for hours at work, begging bosses to let her go on time so she could help her daughter revise for important exams. But she was told she had to stay on in the factory.

“When my elder daughter appeared for a public examination, I was given ‘night duties’ on top of my regular work hours – every day. One day I cried for three hours just to get an early leave, but I wasn’t given any. I couldn’t help her revising, I couldn’t cook on time, she wasn’t fed properly,” the woman said.

Speaking at the end of an 11-hour shift, she said: “We don’t get a choice. The factory only cares about their problems, not ours. It’s terrible.”

Such is the pressure to work and hit targets, she is scared to use her 10-day holiday entitlement. Last year, she took three days; the year before, it was seven.

The male managers are intimidating and regularly shout at machinists, she explained. It is so normal, she said she barely notices any more.

There is a medical facility at the factory and workers can sometimes get sick pay, but on many occasions they do not, the woman added.

She said she once went home during a lunch break and vomited, and had to be taken to a clinic by concerned neighbours, meaning she missed the rest of her shift. She was not paid.

When complimented about how hard she works for her family, she offers a fleeting smile. For the rest of the interview, she soberly describes the hardships in her life.

“I never compromise on my children’s education, so I have to sacrifice a lot of other things like good food, clothes. It is the winter and my kids need warm clothes, but for the last couple of months I’m telling them to wait, but still I am not able to purchase them,” the woman added.

She asked British consumers to consider the circumstances that she and other similar workers face.

“The salary we get is peanuts compared with the enormous pressure we face every day at work,” she said. “The environment is not good either. I just want to address this issue to the global audience that we don’t get paid enough and we work in inhuman conditions here.”

Additional reporting by Redwan Ahmed