- India

- International

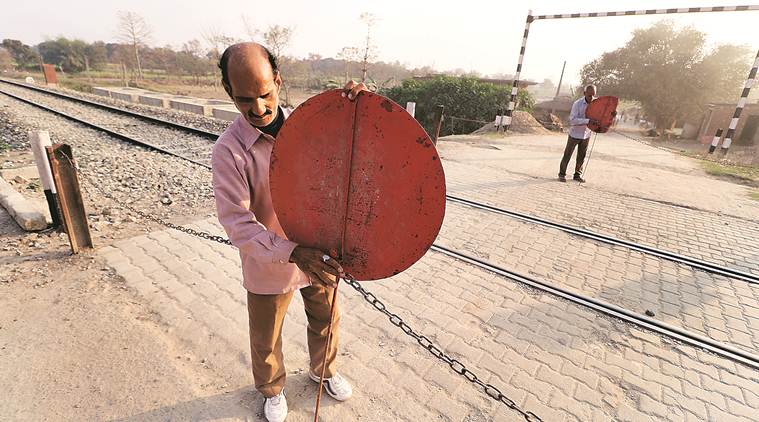

All lines clear: ‘We thought gates will be built after the accident, but we only got two chains’

Nand Kishore, 30, who runs a grocery shop nearby, recalls how 15 days after the accident the chains were installed. “We thought gates will also be built, but that didn’t happen,” he says.

The level crossing has no gates and, last year, on April 26, when 13 children, aged between 8 and 11 years, were killed in an accident at the site, it wasn’t manned either.

The level crossing has no gates and, last year, on April 26, when 13 children, aged between 8 and 11 years, were killed in an accident at the site, it wasn’t manned either.

Around 4 pm, the old cable phone inside the cabin at the Bahpurva railway crossing in Uttar Pradesh’s Kushinagar rings. “Hello 45-C. The train is about to come,” says the station master over the phone. Gateman Prakash Chandra Upadhyay promptly wears his shoes and steps out. As he looks around, the 56-year-old spots children playing on the tracks. Angry, he asks them to leave.

Next, he removes the two red flags that he had placed on the tracks earlier, and then hooks two four-metre-long metal chains to iron poles on either side of the crossing. A few schoolchildren arrive on their bicycles, and after a little pleading, Upadhyay lets them pass through. “We have to be careful,” he says, returning to his position.

Read | All lines clear: Ground reality of unmanned railway crossings

The level crossing has no gates and, last year, on April 26, when 13 children, aged between 8 and 11 years, were killed in an accident at the site, it wasn’t manned either. Around 7 am that day, when the children were on their way to school, their van had rammed into a Gorakhpur-bound train, which dragged the vehicle for a few metres, before throwing it off the track. The driver of the van was accused of negligent driving. He reportedly had earphones on at the time.

“Since I came here from Varanasi three months ago, after completing a month-long training, I have been telling people not to loiter on the tracks but they just don’t listen,” says Upadhyay, a retired Indian Air Force junior warrant officer.

A resident of Basti district, around 140 km from the crossing, Upadhyay works as an ad-hoc gateman in 12-hour shifts. He has been assigned to three different crossings as a reliever, spending two days at each. “It’s a tough job. My family lives in Basti. I don’t get time for any break because I have to manually put up the chains. When I go out to relieve myself, I put the phone close to the window so that I can hear it if it rings,” says Upadhyay.

Soon, around 10-12 bikes and four-five cars halt on either side of the crossing. A few women and children are still sitting on the tracks and on seeing them Upadhyay loses his cool. He yells, but they still don’t listen. “This is what happens every day,” he says, adding, “There are times when people come drunk at night and argue with me to open the chains. There is no security for us. What if someone attacks me? I have thought about it… Maybe I will lock myself in my cabin.”

Five minutes later a passenger train passes by at the speed of 60 kmph.

Nand Kishore, 30, who runs a grocery shop nearby, recalls how 15 days after the accident the chains were installed. “We thought gates will also be built, but that didn’t happen,” he says.

Before the accident, say commuters, the onus was on them to be careful and keep an eye out for trains, as there were no barricades or chains.

Kishore says that since April, people in the area have also started keeping a check on school vans. “If we see a driver not following the rules or driving rashly, we complain to the concerned school and inform the parents too. If the government is not doing its job, we have to take care of each other,” he says.

Apr 19: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05