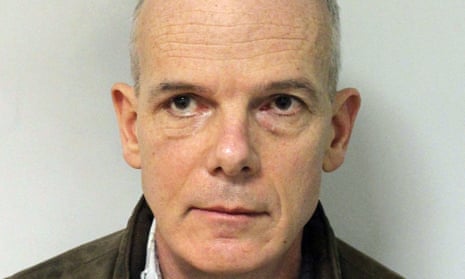

He was “the ghost”, “the one that got away” and the “mastermind” – but most of all he was “Basil”, the mysterious figure at the heart of the £14m Hatton Garden safe deposit burglary in 2015. While five of the team had been swiftly arrested and jailed, the sixth, “Basil”, as he was known to his associates, was nowhere to be found, until last year. On Friday, after more than a week of jury deliberations, he was convicted of his role as the electronics expert in the burglary and jailed for 10 years at Woolwich crown court.

Michael Seed, aka “Basil”, is believed to have let himself into the safe deposit facility in London using a set of keys before disabling the security system. He and another man climbed into the vault through a hole in a thick concrete wall drilled by a gang of criminals and looted 73 safe deposit boxes over the Easter weekend in 2015.

While his fellow burglars shared a traditional criminal past – borstal, Wormwood Scrubs, Parkhurst – Seed’s background could hardly have been more different. The son of a leading Cambridge biochemist, whose nonagenarian mother still lives in the city, he had been a bright schoolboy already fascinated, at the age of 14, by electronics.

After passing A levels in physics, maths, chemistry and geology, he took a degree in electronics at Nottingham University where he embarked on another key phase of his life: using and selling recreational drugs. In 1984, he was jailed for three years for dealing in LSD, his only previous criminal conviction.

After leaving prison, Seed slipped quietly from view. “I’ve always worked in the black economy,” he told the jury. “I don’t pay tax and I don’t claim benefits.” He has lived since 1986 in Islington in London, paying £105 a week rent for a one-bedroom council flat on a small estate where residents are instructed, via large notices, “no exercising of dogs, no ball games” and – significantly, as we shall see – “do not feed the pigeons”.

Inside Seed’s flat, when the police smashed the door down in March last year, was a chaotic trove of electronic gadgetry: blockers, jammers, drills, buzzers, sensors, alarms and half a dozen computers. Amid the detritus of old copies of the electronics magazine Wireless World were newspaper cuttings about Edward Snowden, Peter “Spycatcher” Wright and GCHQ’s eavesdropping abilities. One of his confederates who visited the flat described it as “like Beirut”.

Seed had made a modest living fixing TVs and computers before turning in the 1990s to the recyling and smelting of jewellery and precious metals, a career which, he said, had been suggested to him by a jeweller whose video recorder he was fixing. The police raid left him, according to DC Matt Hollands, “visibly shocked and shaking”.

The 58-year-old, whippet-thin in a pale blue tracksuit as he gave evidence, explained what all this electronic equipment was. His radio jammers, for instance, could be used to block a mobile phone “if the person sitting opposite you on the train is annoying you”.

One jammer was so effective, he explained, that it could block a whole room in a Holloway Road pub. But “my days of jammers were ruined when 3G came along”, he said. A buzzer which reacted to the slightest movement was, he explained, an “anti-pigeon device” to chase the birds from his balcony. Parts of a burglar alarm he had “found on a skip 15 years ago” and had thought of adapting for his mother’s house. The only hint of violence was material related to a “vinyl killer”. This turned out to be a contraption in the form of a miniature campervan which drives round and round an LP, playing its tracks. He had been working on a model for a Japanese company, he said.

It was in a local Wetherspoon’s pub that Seed took his regular weekly form of recreation: heavy drinking sessions. During one of these, he suggested, he might have got hold of the hi-vis BT jacket found in his flat which a drinking friend – whom he would only describe as “short, fat and bald” – who worked for BT might have left behind. “I’m a bit of a hoarder,” he explained with understatement. He owned no property or car, took holidays in Portugal, flying with easyJet or Ryanair, or with his mother and brother in Cornwall.

When the police bugged two of the burglars, Terry Perkins and Danny Jones, just before their arrests, they overheard them chortling about “Basil” and how he “goes for the cheapest gaffs”. Still, he was prepared to take part in the burglary, slipping through the hole drilled in the vault. One of his confederates described him as “game as a bagel”.

His explanation for the 789 items of Hatton Garden jewels and gold found in his flat was that John “Kenny” Collins, one of the burglars, introduced him to a man whom he described as “smartly dressed, late 70s, early 80s” who arrived with the loot.

Asked to name the man, he declined, explaining: “I live in prison.” He said he had not thought that the goods were stolen: “With hindsight, I should have asked.” He had no alibi and could not say what he was doing on the burglary weekend as “I’m not a Filofax person”.

One of the prosecution witnesses was a “forensic gait expert” who would compare the walk of the bewigged “Basil” figure on CCTV at the burglary scene with Seed’s.

Gordon Burrow, a chiropodist with a doctorate in forensic podiatry analysis from Glasgow Caledonian University likened Seed’s walk to that of Charlie Chaplin and said that there was strong support for the belief that the bewigged burglar and Seed were the same.

Throughout the trial, Seed denied being “Basil” which, it has been suggested, stood for “best alarm specialist in London”. But he conceded that “everyone in prison calls me Basil… I’ll be Basil for ever.”

In the US, the convicted conman and forger, Frank Abagnale, who impersonated pilots and doctors and whose life was turned into a film, Catch Me If You Can, starring Leonardo DiCaprio, now has his own security advice company and gives lectures to the FBI. “Perception is reality,” he told me when I asked him a few years ago about the secrets of being a good con man. “What people see is what they believe.”

For Basil, the perception has now turned into the reality of years in jail but, in the words of those old acid-heads the Grateful Dead, whom he doubtless listened to in his student days, “what a long strange trip it’s been”. When he emerges from his 10-year sentence, there would be, if the interest shown by reporters and lawyers at the trial is anything to go by, no shortage of investors in Basil’s Pigeon Chaser or Basil’s Irritating Mobile Phone Blocker.

The cons with special powers

Michael Seed is part of a long line of criminals whose special abilities could have been profitably put to other uses.

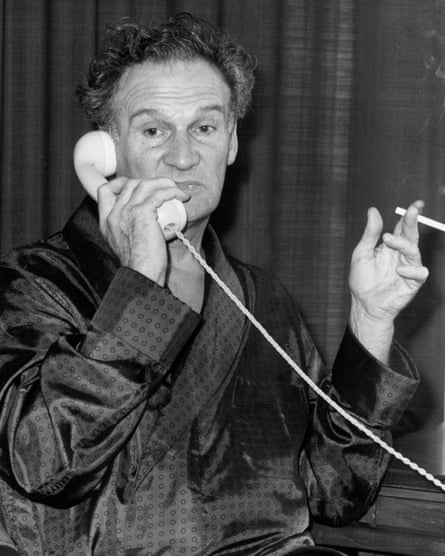

The 1930s safecrackers Eddie Chapman and Johnny Ramensky, both put their remarkable skills to the service of the allies in the second world war. Chapman became the double agent, ZigZag, and Ramensky went from Peterhead prison to crack Nazi safes behind enemy lines. The cat burglar Peter Scott, always said that he was essentially just a “dishonest window-cleaner” and gang leader Charlie Richardson, after his release from a 25-year sentence, went successfully into business in the City, which he described as “much more dishonest that anything I was ever involved in”.