About three years ago, the Moroccan-American author Laila Lalami flew across the country from her home in California to Rhode Island to give a talk about who does and doesn’t get to tell their story. As she spoke, she noticed a young undergraduate – white, male – in the front row, sighing wearily.

“Is it upsetting to you to hear this?” she asked.

“Yes, because no one’s stopping you from talking about your story,” he replied.

“OK, consider what your average newsroom in this country looks like,” Lalami responded. “It is primarily white, it is primarily male and it is primarily straight, and every news story you read comes through that filter,” she said. He shrugged at her, neither arguing the point nor conceding it.

“Young men like him have not had the experience of not seeing themselves on screen or in stories, hearing perspectives that don’t include them – the ‘we’ is always them,” Lalami tells me. “So they have trouble understanding when someone says, ‘I don’t have that.’ The realm of their imagination is so narrow that they perceive it as a demand on your part to take control of the narrative when all you’re asking for is representation,” she says over a plate of brightly coloured macaroons in her apartment in Santa Monica, Los Angeles.

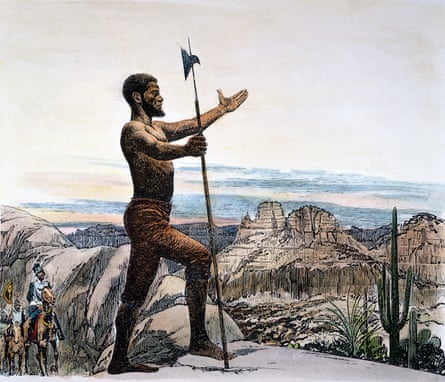

Throughout her career, Lalami has focused on giving a voice to the normally voiceless, including herself, a female Muslim immigrant in the US. She was an early enthusiast of blogging because, she says, “I had things I wanted to say, especially after 9/11, and nowhere to say them.” (Today, she contributes regularly to, among others, the Nation and the New York Times.) Her first novel, Secret Son (2009), featured a fatherless boy in a Casablanca slum. In The Moor’s Account (2015) – which won the American book award, was a finalist for the Pulitzer and longlisted for the Man Booker prize – she retold the true story of the disastrous Narváez expedition, in which a largely Spanish crew of 600 sailed to America in 1527, and only four survived. But whereas historians had previously concentrated on the three Spanish survivors, Lalami gives the narrative to the one person remaining about whom almost nothing was known, a Moroccan slave called Estebanico.

“When I read about [the Narváez expedition], it felt very much of the here and now that one person wouldn’t get to tell his story. All I have to do is pick up a newspaper and, for example, they’re talking about family separations, and it will quote the officials but how many of the families get to talk?” Lalami says.

She opens her new book, The Other Americans, with the sudden death of Driss, a Moroccan-American immigrant who has lived in the US for 30 years. The story of what happens next is told through the viewpoints of various people: Driss’s wife, Maryam, who has never adjusted to US life; an illegal immigrant called Efrain, who is terrified of attracting the authorities’ attention; a former US Marine suffering PTSD; and a young American man called AJ whose life hasn’t worked out as he expected. Driss and Maryam’s younger daughter, Nora, who was born in the US, repeatedly encounters minor instances of racism – at a music festival she is mistaken for a waiter instead of the composer she is – but AJ, who was her classmate at school, feels it is he who is seen as out of place in a country that is changing too rapidly: “It’s funny, everyone goes on and on about celebrating diverse cultures, but the minute you bring up white culture, the oh-so enlightened liberals turn on you and call you names,” he says. It is impossible to read AJ’s sections without imagining him in a Make America Great Again hat. The Moor’s Account felt like a product of the Obama era, given that it looked at the role immigration, and in particular a man of African heritage, played in the American story. By contrast, The Other Americans – from its title onwards – reads like a response to the Trump era.

Lalami is a small woman with a big laugh and she laughingly but firmly denies the book is simply a response to Trump, having started work on it in 2014. But she concedes that, yes, she did begin to see the story differently after the 2016 election. “Trump is the kind of man who strips subtext out of everything and just renders it as text. He’s made people much more conscious of, for example, what’s going on with immigration policy, which is why the same book can be read very differently before and after his election. It’s not like before Trump everything was wonderful and after Trump everything was terrible, but there’s no question in my mind that Donald Trump has certainly emboldened people.”

Just two weeks after Lalami and I meet in her apartment, 50 people are massacred in a mosque and at an Islamic Centre in Christchurch, New Zealand. I email Lalami to ask if the tragedy surprised her:

“I wasn’t surprised in the least,” she writes back almost instantly. “Anti-Muslim rhetoric has been on the rise for quite some time, often stoked by politicians to win votes, whether at the local or presidential level. The white supremacist movement is finding new recruits online and the result is clear: white supremacists have targeted Muslims in New Zealand, Jews in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, African Americans in Charleston, South Carolina, to name just three examples ... yet lawmakers aren’t taking the threat as seriously as other forms of terror.”

More than immigration, Lalami’s specific interest is humankind’s repeated failure to recognise our collective humanity across class, national and racial divides. In 2009 she wrote an article for World Literature Today about realising that so many of the books she had grown up reading as a child in Rabat were written by white men who exoticised their foreign characters beyond recognition.

“The surrogate storytellers told a version of Morocco – mysterious, exotic, at once overly sexual and sexually repressed – that seemed entirely removed from my reality or indeed the reality of others around me … As I was finishing graduate school, my writing path became quite clear to me. I had always told stories, but now I wanted to be heard,” she wrote.

In her books, Lalami captures the ordinary sensory details that humanise an experience which may initially seem unimaginable to the reader. In The Moor’s Account, the noises and smells Estebanico notices around him are as revealing of 16th-century America as they are of Estebanico himself: “Whenever I think back about that summer, what I remember most is how the sound of the cracking nutshells filled the entire valley. Other sounds added to that cacophony: new arrivals pitching their tents, neighbours calling to one another, children playing hide and seek, the wind rustling through the leaves of the nut trees … ” In The Other Americans, Maryam recalls her desperate attempts to make conversation with a woman in a supermarket soon after arriving in the US, only to be floored by “the betrayal of a foreign tongue” and resorting to bad miming.

“It’s the individual storytellers who interest me and their day-to-day experiences, rather than a sweeping story about immigration, because immigration is one of the most ordinary human experiences there is. It shouldn’t be treated as exotic,” she says.

Lalami was born and raised in Rabat. Her father worked for the department of water and power and her mother was a homemaker. Neither of her parents finished school, but they loved reading and their home was always full of books. Lalami’s mother was an orphan (her experiences inspired the character of Rachida, the mother who grew up in an orphanage in Secret Son), and this lack of familial connections meant Lalami always felt like an outsider, even in her own country.

“In Morocco, a lot of what determines your power in society is class and who your family knows. So not having any family on my mother’s side always set me apart from the other kids at school,” she says.

This feeling of separateness – of being, as she puts it, “the person in the corner observing everything but who no one pays attention to” – would become a running theme in her life. Despite being working class, her parents sent her to a French-speaking school, usually the choice of upper-class families, “so that was another feeling of, you’re in here but not of us,” she says. Lalami grew up speaking Arabic at home, French at school and, eventually, English at work, and this flowing between different languages taught her that the usual barriers between people are more porous than most assume.

Lalami knew from an early age that she wanted to be a writer. But despite being avid readers, her parents were horrified. “You have to remember, this was Morocco in the 1980s and the only time you heard about a writer then was because they were in trouble with the government, and journalists were being jailed. So from their perspective, it wasn’t a particularly good place to be a writer.”

So she tried to distract herself from her dreams by studying, first English at university in Rabat, and then linguistics at UCL. But despite loving UCL, London proved to be a less than cheering experience. “OK, so I love London, I do,” Lalami begins apologetically. “But the weather was a big issue for me – it rained so much and was so depressing. It was a very lonely time.”

It was also the beginning of the Gulf war, and the way the British media wrote about the Middle East contributed to Lalami’s feelings of separateness. “When you come from a country in the global south, you have an acute sense of your country’s powerlessness on the world stage. But moving to England and seeing how the newspapers covered the Middle East and north Africa, you realise anything associated with north Africa or the Middle East was described in dichotomies of good or evil, and we were on the evil side,” she says.

After UCL, she went to the sunnier city of Los Angeles, to do a PhD in linguistics. At the time she planned to stay just long enough to do her coursework, and then return to Morocco to write her dissertation. But one day at university she was having trouble with her computer and a fellow student, a handsome Cuban-American man, fixed it. “Isn’t that nice of him?” she thought. They eventually got married. “And 18 years later, he’s still fixing my computer,” she smiles.

Lalami, her husband and their teenage daughter live on a grassy, palm tree-lined street, just 20 minutes away from the beach. Two blocks from her house someone put up a sign that says: “Wherever you’re from, we’re glad you’re our neighbour.” But as Lalami stresses, liberal, picturesque Santa Monica is no more representative of the US than she – secure, successful – is of the typical immigrant experience.

“I have, in many ways, this perfect immigrant’s life, I don’t have to worry about papers, where my next meal comes from. But even in this best case scenario, I turn on the news and hear I’m only here to steal people’s jobs,” she says.

In 2000, shortly before the Bush/Gore election, Lalami became a US citizen, and despite all the recently amped-up anti-immigrant rhetoric, she describes herself as being “in a committed relationship with America”: “When you become a US citizen, you don’t stop loving your own country – you just expand your notion of what you love. But also, to be an immigrant means you’ve crossed two thresholds between two countries, and you know that things will never be black and white again.”