- India

- International

Hardlook: The invisibles

A slum cluster that found itself under the shadow of demolition three years ago is now in the spotlight because of a landmark High Court judgment that highlights right to the city for all. Sukrita Baruah heads to Shakur Basti to understand what’s changed, and what hasn’t, since then.

In a city where the 2011 Census estimated a slum-dwelling population of 17,85,390 and where there have been over 200 forced evictions in the last 10 years, the judgment, with its emphasis on the Right to the City, is a significant one. (EXPRESS PHOTO BY PRAVEEN KHANNA)

In a city where the 2011 Census estimated a slum-dwelling population of 17,85,390 and where there have been over 200 forced evictions in the last 10 years, the judgment, with its emphasis on the Right to the City, is a significant one. (EXPRESS PHOTO BY PRAVEEN KHANNA)

“The right to housing is a bundle of rights not limited to bare shelter over one’s head. It includes the right to livelihood, right to health, right to education and right to food, including right to clean drinking water, sewerage and transport facilities.”

“The law explained by the Supreme Court in several of its decisions and the decision in Sudama Singh discourage a narrow view of the dweller in a JJ (jhuggi jhopdi) basti or jhuggi as an illegal occupant without rights. They acknowledge that the right to adequate housing is a right to several facets that preserve the capability of a person to enjoy the freedom to live in the city. They recognise such persons as rights bearers whose full panoply of constitutional guarantees require recognition, protection and enforcement.”

“Once a JJ basti/cluster is eligible for rehabilitation, the agencies should cease viewing the JJ dwellers therein as ‘illegal encroachers’”. Over three years ago, on December 12, 2015, the homes of 5,000 people living in Shakur Basti, a JJ cluster in West Delhi, were demolished in an attempt to evict them from land held by the Indian Railways. After three years of living insecurely and scrambling to claim their rights, the Delhi High Court last week disposed of their petition and made the aforementioned observations.

It also made it clear that there is no imminent possibility of their eviction until a survey is conducted; arrangements for rehabilitation are made; and if relocation is required, they are given adequate time to move to the new site — a principle to be followed in the case of any eviction.

In a city where the 2011 Census estimated a slum-dwelling population of 17,85,390 and where there have been over 200 forced evictions in the last 10 years, the judgment, with its emphasis on the Right to the City, is a significant one. Back in Shakur Basti — which was chosen by Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal to launch his election campaign till he was denied permission on account of the area being too congested — the judgment brings hope of a life with some permanence. The living conditions, though, leave a lot to be desired.

***

So closely tied is this work to the lives of the people of Shakur Basti that they say the settlement came up when the cement unloading site was shifted here. (EXPRESS PHOTO BY PRAVEEN KHANNA)

So closely tied is this work to the lives of the people of Shakur Basti that they say the settlement came up when the cement unloading site was shifted here. (EXPRESS PHOTO BY PRAVEEN KHANNA)

Sitting under the shade of a banyan tree, a group of men wait for the next train to roll into the Shakur Basti Railway Station. Around half the male population of the settlement earns its livelihood unloading sacks of cement from trains that halt at the station, and loading them onto trucks waiting nearby. “We earn Rs 4 for every sack we load and unload. Eight of us work on unloading a bogey, which has 1,400 sacks. The trains come two or three days in a week, but we never know when the next one will arrive as there’s no schedule. So we spend our days waiting,” said Mohammad Monobar (35), whose home is a few steps away.

So closely tied is this work to the lives of the people of Shakur Basti that they say the settlement came up when the cement unloading site was shifted here. “The unloading site used to be at Ajmeri Gate and was shifted here in 1978. People who did this work followed it here, found empty unkempt land next to the railway station, and started living here. Now only a handful of the people who worked back in Ajmeri Gate survive,” said Mohammad Fakhruddin (60).

The men laugh about their relationship with the railways. “Most of the people doing this work die by the age of 50 because of the large amounts of cement dust we inhale. We live and die working at the railway station, and we are also chased away because of the railway station,” said Monobar.

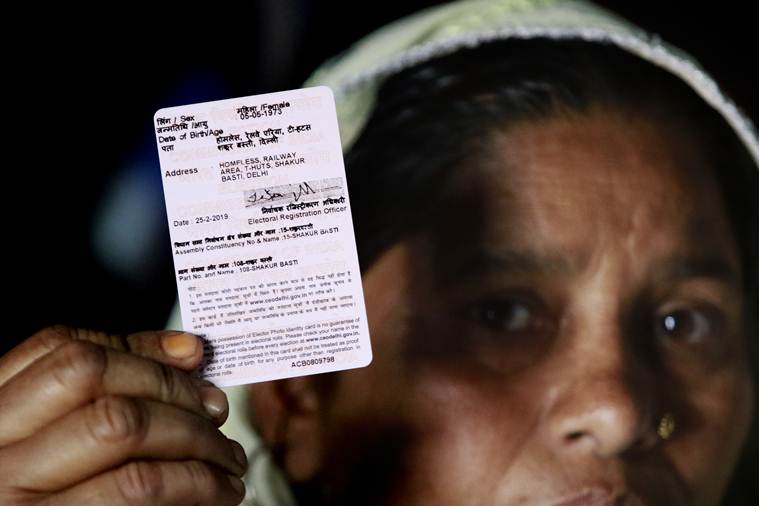

Nasreen Khatoon, resident of Shakur Basti who’s address had changed in new Election card. (EXPRESS PHOTO BY PRAVEEN KHANNA)

Nasreen Khatoon, resident of Shakur Basti who’s address had changed in new Election card. (EXPRESS PHOTO BY PRAVEEN KHANNA)

At the Delhi High Court, the Railways had submitted that the eviction had been carried out as the area of around six hectares was under “soft encroachment” and needed to be developed “for passenger amenities like platforms and other facilities” to decongest New Delhi and Old Delhi Railway Stations.

In its order dated December 14, 2015, the court had also stated that it had been informed that “the Railways were concerned about the safety of persons living perilously close to the tracks and that the forced eviction was to ensure they are not exposed to risks”. However, the court observed that the eviction drive had exposed the people to perhaps graver risk, particularly because it had taken place during the biting cold of December.

On December 16, 2015, the court had stated the demolition was “contrary to the requirements of the law and the Constitution” as it had taken place without prior survey to determine how many of the residents were entitled to rehabilitation. Chief PRO of Northern Railways Deepak Kumar said that a full response to the judgment is only possible after going through it comprehensively. “On the face of it, I can say demolitions are part of the Railways’ drive as they are occupying land in an unauthorised manner,” he said.

***

Mohammad Noor Alam Khan, Father of the boy who died due to snake bite. (EXPRESS PHOTO BY PRAVEEN KHANNA)

Mohammad Noor Alam Khan, Father of the boy who died due to snake bite. (EXPRESS PHOTO BY PRAVEEN KHANNA)

The brick walls of Safina Khatoon and Mohammad Anwar’s home stop at the height of four feet. The rest of the structure, its roof, ceiling, and door are tarpaulin sheets, supported by planks of wood.

“After the demolition, the Delhi government had given us tarpaulin sheets. We made tents out of those and lived like that for a year. Gradually, we began building these walls. Even when we were building, police came and broke down a portion of it. We left it at this much because we don’t want to put in money and effort just for someone to come and break down our home. Unless we can expect something better, we can’t move forward,” said Safina’s father Mohammad Kalimuddin, who lives in a similar adjacent structure.

This uncertainty can be seen across the more than 1,000 homes. Residents have been living in homes of plastic and cloth sheets, and even saris, through the extreme seasons of the last three years. “Any attempt to make ourselves even a little settled results in a backlash. A few days ago, we were laying rubble on the paths because the area gets waterlogged during the rain. Soon, the railway police came to stop us,” claimed Virendra Kohli, who has been at the forefront of the community’s struggle in court.

On the orders of the court, some basic amenities have been provided. (EXPRESS PHOTO BY PRAVEEN KHANNA)

On the orders of the court, some basic amenities have been provided. (EXPRESS PHOTO BY PRAVEEN KHANNA)

For Safina, the years have been more difficult than for most. In a city where most evictions go by unnoticed, the Shakur Basti demolition gained public attention due to the death of a six-month old baby girl — her youngest daughter Rookia. While the family claims a bundle of clothes and belongings fell on the infant when she was sleeping alone, while her family was consumed by the rush and tumble of the demolition, they found themselves faced with a criminal case for causing death by negligence. “We have been going to court on the allotted dates every two-three months now. The hearings have not begun,” said Safina, who was 21 at the time.

On the orders of the court, some basic amenities have been provided. Last year, four toilets with 30 cubicles each were installed by the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (DUSIB). Some mobile toilets were also provided immediately after the demolition, but residents said those never had water.

Five DJB tankers visit in the evenings, so women can fill buckets for their households, but there is no running water. Hand pumps scattered across the settlement yield brackish water. Electricity connections were installed but only in a handful of houses, and a vast majority of households have been getting by without electricity for three years now.

***

Five DJB tankers visit in the evenings, so women can fill buckets for their households, but there is no running water. (EXPRESS PHOTO BY PRAVEEN KHANNA)

Five DJB tankers visit in the evenings, so women can fill buckets for their households, but there is no running water. (EXPRESS PHOTO BY PRAVEEN KHANNA)

A joint survey undertaken by DUSIB and the Railways after the demolition found that 4,968 people from 1,362 families had been affected by it. Of this, 1,890 were below 18 years of age, and 46 over the age of 60. Of the rest, 885 were women and 2,147 men.

Residents also work as daily wage labourers and rickshaw pullers, while women work as domestic helpers in areas such as Punjabi Bagh and Rani Bagh. Children study at nearby MCD and Delhi government schools. Residents said that for a few months after the demolition, people were unable to work as they were living in the open and needed to watch over what remained of their possessions.

The role played by residents of Shakur Basti, and of several other JJ clusters, had found a mention in the High Court judgment: “The Right to the City acknowledges that those living in JJ clusters in jhuggis/slums continue to contribute to the social and economic life of a city. These could include those catering to the basic amenities of an urban population, and in the context of Delhi, it would include sanitation workers, garbage collectors, domestic help, rickshaw pullers, labourers and a wide range of service providers indispensable to a healthy urban life. Many travel long distances to reach the city, and many continue to live in deplorable conditions, suffering indignities just to make sure the rest of the population is able to live a comfortable life…”

According to Abdul Shakeel, a member of the Basti Surakhsa Manch, this concept is crucial to housing rights advocacy. “The narrative around the city is always about what the middle class and upper middle class want… around flyovers, highways and expressways. The middle class claims the city belongs to them, while the working class is seen as encroachers and migrants. Their informal, invisible labour which holds the city together is not recognised. An inclusive idea of right to the city can help them claim their rights to space,” he said, adding, “The High Court judgment is a positive one and comes as a relief. It remains to be seen how central land-owning agencies interpret it and if they appeal against it. But one thing is for sure — at least for now, Shakur Basti is safe.”

Shakur Basti & Beyond: Pre-eviction process laid out in DUSIB’s draft protocol

In light of the Shakur Basti case, the Delhi High Court directed that DUSIB frame a draft protocol in consultation with other land-owning agencies for a uniform approach with regard to all jhuggis and bastis in Delhi. In last week’s judgment, the court gave DUSIB the go-ahead to operationalise the draft protocol, in which the cut-off dates in its 2015 Delhi Slum and JJ Rehabilitation and Relocation Policy is to be applied uniformly across Delhi

The process laid down in the Draft Protocol:

* Land owning agency (LOA) concerned to send a proposal for removal to DUSIB sufficiently in advance “with proper justification… along with commitment to pay cost of rehabilitation”

* DUSIB to examine proposal with reference to cut-off date and undertake joint survey, along with representatives of LOA, to determine eligibility of JJ dwellers for rehabilitation as per the 2015 DUSIB policy

* Eligibility Determination Committee (EDC), Claim and Objection Redressal Committee to be constituted

* Finalised list of eligible, ineligible JJ dwellers to be submitted by EDC to CEO DUSIB for approval. Appellate Authority to be provided list so ‘genuine’ left-out cases can appeal

* After receiving cost of rehabilitation, DUSIB to conduct draw of flats to be allotted to those eligible

* After letters are issued, JJ dwellers to be given two months for shifting, after which steps can be taken for removal of the jhuggis with police help. DUSIB to facilitate “transport of household articles/belongings of eligible JJ dwellers to the place of alternative accommodation, if necessary”

* Demolition and shifting cannot be carried out at night, during annual examinations or extreme weather conditions

* Facilities to be provided at site of rehabilitation

* Admission of children in nearby schools

* Dispensary/mohalla clinic in the vicinity

* Fair price/cooperative store in the area

* DTC buses, drinking water, sewerage system

Apr 19: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05