- India

- International

The ‘Jallianwala Bagh Centenary Commemoration Exhibition’ sheds light on the fateful massacre

Using the help of unknown facts and intimate details of what happened before and after the massacre, it examines whether the fateful event was a well-planned conspiracy by Dyer to confine those gathered inside the premises, which was devoid of any escape route.

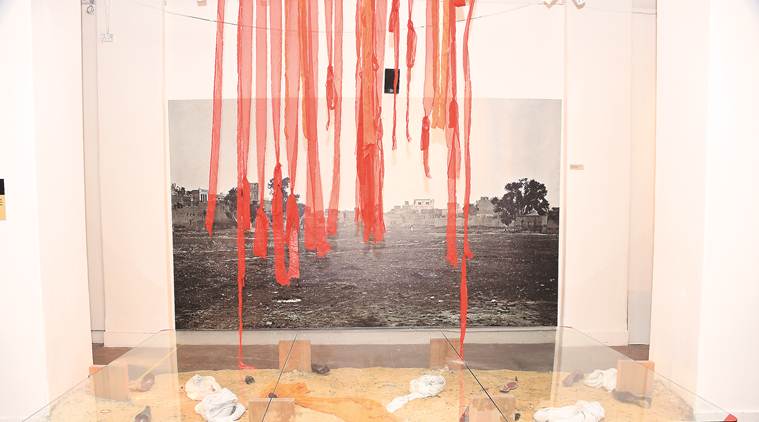

The tribute installation at IGNCA

The tribute installation at IGNCA

Colourful turbans and juttis, including those of children, lie spilled around an installation made of mud on the floor of Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA), New Delhi. A reminder of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, when the ground was laden with bodies and their belongings, ones that lay there for weeks after the shootings on April 13, 1919. At the “Jallianwala Bagh Centenary Commemoration Exhibition (1919–2019)”, on display till April 28, eye witness accounts from ‘The Congress Committee Report, Vols I & II’, pop up alongside. One of them is that of Lala Nathu Ram, who searched almost every dead person till he found his 25-year-old brother, lying under four dead bodies. Another witness Girdhari Lal said back then, “people were hurrying up and many had to leave their dead and wounded because they were afraid of being fired upon again after 8 pm.” His quote is the text on a wall.

Accompanying texts go on to mention how Dyer had banned public meetings through announcements in Urdu and Punjabi at 19 places in Amritsar, but none were made near the Jallianwala Bagh and the people were not prevented from gathering. Soon after 5 pm on the dreadful day, Brigadier General Reginald Dyer, entered with 50 soldiers, and without any warning, fired 1650 rounds on unarmed protesters, a little after an airplane flew overhead, “probably to report back to Dyer that a crowd had gathered”.

Kishwar Desai

Kishwar Desai

Many similar photographs, text data from newspapers and reports, objects and art installations together form the crux of the exhibition, being presented by the IGNCA and The Arts and Cultural Heritage Trust (TAACHT) to commemorate a century since the incident.

Using the help of unknown facts and intimate details of what happened before and after the massacre, it examines whether the fateful event was a well-planned conspiracy by Dyer to confine those gathered inside the premises, which was devoid of any escape route. Having researched the subject extensively, Kishwar Desai, Chairperson of TAACHT, says, “People of Punjab were unhappy due to forced recruitment of soldiers for the First World War. In fact people made payments so that their children wouldn’t go for the war as soldiers, and somebody else could take their place.”

Alongside photos of Indian soldiers marching from the Imperial War Museum, are portraits of Kartar Singh Sarabha, one of the founding members of the Ghadar Party, hung at the age of 19 for propagating the Ghadar rebellion, and party President Sohan Singh Bhakna, imprisoned for 16 years for the same reason. Sir Michael O’Dwyer, then the Lieutenant-Governor of Punjab, ruthless in putting thousands behind bars, tried his best to suppress the movement.

Bullet marks from the firing Picture Street

Bullet marks from the firing Picture Street

“This was a movement that was based out of San Francisco. Indians would come back and realise that there was a lot of freedom abroad. The same happened to the Indian soldiers who felt that although they had been fighting for the British abroad, they didn’t have any independence when they returned home,” says Desai, who began researching on the subject when she saw Town Hall in Amritsar destroyed in a photograph dated April 10, 1919, while researching for her book Jallianwala Bagh, 1919: The Real Story.

Extracts from the report of the committee appointed by the government of India to investigate the disturbances in Punjab reveal Dyer’s responses to the necessity of that day’s firing. “I could disperse them for sometime, then they would all come back and laugh at me. I considered I would be making myself a fool,” he’d said. On being asked if his idea in taking the action was to strike terror, Dyer answered, “Call it what you like?… My idea from the military point of view was to make a wide impression. I wanted to reduce their morale, the morale of the rebels.”

A profile photograph of Udham Singh crops up. Born in Sunam, Punjab, he went to London to avenge the massacre and shot O’Dwyer, the lieutenant governor of Punjab then. Singh was hung after a swift trial the same year.

While most official records list the number of dead people at 379, TAACHT, through its research, lists it at 547. Desai says, “There must have been at least a thousand killed. A lot of people ran home and they were too scared to report that they were at the Bagh, and died at home and their families never reported to avoid trouble. The British would just come and pick up the male members of the family because they felt the Jallianwala Bagh meeting was a meeting to overthrow the British. In reality, it was actually a satyagraha against the Rowlatt Act, which had been called by Mahatma Gandhi and it was a meeting to request the release of leaders behind bars. It was a very peaceful meeting. They had no guns.”

Apr 16: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05