By Marc Passen

Adios, my Shana Rivka (Beautiful Ruth).

Shana Rivka was a pet name for Ruth Passen used by her devoted and adoring brothers. Ruth was a first-generation Californian, born in San Francisco to Morris and Nettie Elkind, who emigrated from Russia and Poland to escape discrimination against Jews. Ruth was the baby sister to her older brothers, Sam and Charles (Chuck). She was predeceased by Sam. Chuck resides in Southern California.

Ruth grew up in the Fillmore District when the neighborhood was a mix of Jewish, African- and Japanese-American families. She gained an appreciation of diverse cultures through the community’s natural integration. “My dad’s philosophy was a good one,” she once said. “He felt that as a Jew you should know about discrimination and not discriminate against others.” Ruth attended John Swett Junior and Lowell high schools.

Ruth became politically active at a young age. While attending classes at San Francisco State University she joined a left-wing student group, where she met World War II veteran, Joe Passen, who passed away in 1992. They married in 1947, shortly after Sam wedded Betty Glass and right before Chuck married Rockie (Rokama) Kramer. Rockie fondly recalls a time when Ruth took her new sister-in-law shopping at a discount dented can store. Rockie was hooked, and became a lifetime thrifty shopper! A son, Marc, was born in 1950. A second baby, Nicky, was born in 1951 and predeceased Ruth in 1963.

In the early 1950s, Ruth’s passion for progressive politics led her to speak out against the McCarthy era of hate and divisiveness.

After living in Los Angeles for seven years, Ruth missed her beloved San Francisco. She and Joe found a home on Potrero Hill and moved back in 1965. During the turbulent 1960s, Ruth became active in the anti-Vietnam War movement, and joined the Women’s Peace movement. In the 1970s, Ruth supported workers’ rights during the grape boycott led by United Farm Workers president Cesar Chavez.

In the late 1970s, Enola Maxwell, Potrero Hill Neighborhood House (Nabe) director, hired Ruth to become the Nabe’s office manager. It turned into a wonderful collaboration and friendship between two dynamic women.

During this period, Ruth got involved with an upstart neighborhood newspaper, Hills & Dales, which later changed its name to The Potrero View. Ruth became the editor of the free monthly paper, holding that position for more than three decades. She recruited people to volunteer, write, and proofread stories. The publication featured investigative reports on development plans, stories about crime, mom and pop businesses, and even a gossip column, “The Nose Knows.” Friends, neighbors, acquaintances, even a 49er football player would find their name under the “Birthdays” column. Ruth retired from the View in 2008, turning the reins over to Steven Moss.

Over the years, Ruth and Joe were strong supporters of liberal-progressive Democratic candidates running for the U.S. House of Representatives. They hosted many fundraising events for Phillip Burton, Sala Burton and Nancy Pelosi. In the late-1980s, Ruth and Joe helped Art Agnos get elected mayor of San Francisco. When Pelosi became the first woman Speaker of the House, Ruth received a personal invitation to attend the swearing-in event in Washington, D.C.

When Ruth took a break from trying to save the world, she loved to listen to jazz, opera, classical music, and Broadway musicals. Ruth and her “bosom buddy”, Denise Kessler, religiously attend the annual Monterrey Jazz Festival in the 1950s and 1960s. They loved jazz so much that they booked passage on a jazz cruise to the Bahamas, featuring the Count Basie band! Ruth and Joe were season ticketholders of the San Francisco Symphony and the San Francisco 49ers. Ruth loved to travel, taking annual summer trips to Camp Mather, near Yosemite National Park, visiting New York City, London, and Paris. When Marc started playing rugby football, Ruth became not only a big fan, but a fantastic sideline photographer of the sport.

Ruth had a way of connecting with people. Her easygoing style, wisdom, and acceptance created a space for others to share things with her that they weren’t comfortable revealing to anyone else.

Ruth adored her two granddaughters, Natalie and Teresa. When the girls were little, she’d take them to Sally’s, Goat Hill Pizza, and the Daily Scoop, where she’d proudly show them off. At Ruth’s Rhode Island Street apartment, the girls would get her to smile and laugh, draping themselves with her silk scarves and posing as models. As the girls got older, Ruth would take them on marches against the Iraq War and on Martin Luther King Day.

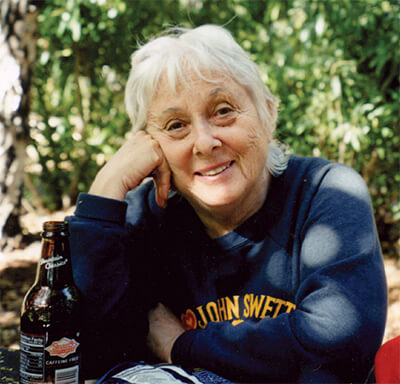

She had a “forever young” persona that was never more evident than how she related to young people. Whether it was her granddaughters, nieces or nephews, or the Black and Brown kids at the Nabe, this little, grey-haired White lady had such an impact that those who knew her would approach years later to thank her for just listening and being direct and honest.

Over her lifetime, Ruth consistently demonstrated compassion and devotion to the causes of freedom, peace, and equality. She deservedly received the great love and respect by all who were fortunate to have known her. She will remain in our hearts forever.

Ruth is survived by Marc and his wife, Dianne, granddaughters Natalie Carsten and Teresa Sollom, Chuck Elkind and his wife, Rokama Elkind, and many nieces and nephews.

The family will hold a tribute and memorial to Ruth on May 4, 2 p.m. at the Potrero Hill Neighborhood House. In lieu of flowers, please consider a donation to the Alzheimer’s Association.

Aunt Ruth

by Risa Nye

Aunt Ruth used to chide me when I complained about being exhausted after chasing my young children around.

“In my day,” she said, “we’d put the kids to bed, and then figure out how to save the world!”

Saving the world meant throwing herself into the fray. She’d hoist a sign, march and demonstrate in the streets; for civil rights, social justice, against the bomb, the war, the next war, and the next. She kept her vast collection of politically-inspired buttons pinned to a large piece of felt, ready to stick on her hat or jacket as she headed off to the next rally or picket line: We Shall Overcome. Make Love, Not War. Another Mother for Peace.

I loved the time we spent together during my summer visits to my aunt and uncle’s crowded Los Angeles apartment. During these critical pre-teen years, Aunt Ruth matter-of-factly shared some important tips. She showed me how to apply three shades of lipstick, how to shave my legs without nicking divots into my shins, and how to have fun while shopping, things my mother hadn’t taught me.

A constant parade of unemployed writers, between-gig actors, labor organizers, and fellow progressives showed up at the L.A. apartment, arguing politics over red wine and plates of pasta long into the night. Hugs and handshakes always followed the loud voices and f-bombs at evening’s end. Things were not like that at my house.

When her family moved back home to San Francisco, my aunt began contributing articles and photographs to her neighborhood newspaper. She subsequently took on the roles of editor and publisher of The Potrero View, a three-decades-long labor of love. At the Potrero Hill Neighborhood House she helped organize afterschool programs, classes for adults, and events that celebrated the scrappy diversity of the “Nabe.”

At an event honoring my aunt for her work, San Francisco’s mayor read a proclamation loaded with “whereases,” and declared a day in her honor. When he finished speaking, my father leaned toward me and pointed proudly at his “baby” sister. “Look at her; she’s the richest person in this room.” And I knew what he meant.

My aunt encouraged me to write, publishing my essays in her paper; my first bylines. Writing was her passion. She talked about composing a memoir, but never started it. “I’m not a writer like you,” she told me once. “You do it for both of us.”

Ruth never pandered to anyone. You could always count on her to be outspoken, feisty, honest, but kind, and a champion of the underdog. She would confront racism or social injustice wherever she found it, no matter who the guilty party might be. And she mastered the art of being cool without even trying.

When I went back to graduate school at age 58, I hoped I could model myself after Ruth. She was always able to engage effortlessly with everyone: young and old, well-off and well-connected, or down-on-their luck. I often asked myself: “what would Ruth do?” And I knew that she’d act like it was no big deal to be sitting in workshop with students a few decades younger. I could imagine her saying, “Get over yourself and do the work you came to do.”

In her 80’s, Ruth slipped into the foggy world of dementia. It’s not the world she tried to save so many years ago, but it was the world she lived in until her death. The sparkle was still in her eyes. At least, that’s what I wanted to see. And I told myself that she may not recognize me anymore, but she knew I was someone who always loved her.