This story is part of an ongoing series exploring the real-life struggles of Western North Carolina residents who are experiencing food insecurity. In this case, the irregular nature of the subject’s situation has made communication more difficult; Xpress has interviewed him multiple times since last December, however, and has explored various avenues to confirm details of his story.

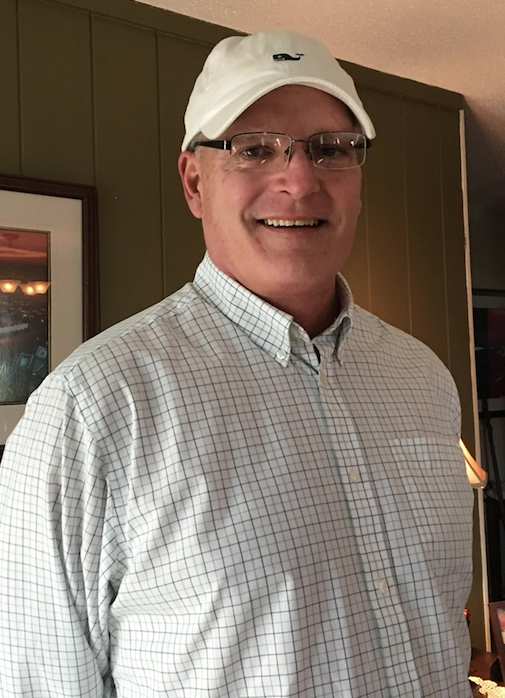

On a good day, U.S. Army veteran Michael LeBlanc might be found helping someone with a remodeling project or volunteering at a local charity. On a bad day, though, he might be the man who approaches you in a parking lot, begging for spare change.

Those bad days tend to happen when the 55-year-old’s disability check has been spent and he’s used up his monthly allotment from the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, which he says was reduced to just $15 once he qualified for disability payments. At that point, he does whatever he can to get enough food to make it through the month.

LeBlanc says his bad days are very much tied to the constant pain he’s experienced since he sustained a traumatic spine injury during his Army service in the late 1980s. According to LeBlanc, he was injured when a military plane crashed in Alaska, where he was working as a loadmaster and driver.

The pain, which he says often flares into the unbearable orange and red zones at the far right of the pain scale, has made it impossible for him to keep a job. It’s also the driving force behind a nearly 30-year, off-and-on addiction to painkillers and alcohol.

“There’s a little chart over [at the Charles George VA Medical Center in Asheville] numbered 1 to 10,” says LeBlanc. “When it gets to 10, it says ‘Nothing Else Matters,’ and that’s it: Nothing. Else. Matters.” He says he’s been off opioid painkillers for more than two years but often drinks alcohol to cope. “When it gets to 10, I say screw it, and I really shouldn’t, because [drinking] is another struggle for me.”

Another challenge LeBlanc faces is post-traumatic stress disorder: He served in the first Gulf War and says he also participated in the U.S. invasion of Panama. For his PTSD, he receives a monthly disability check of about $1,000 from the Department of Veterans Affairs, which is what he lives on.

The pain and PTSD have taken over his life, says LeBlanc, ultimately rendering him homeless, addicted, unemployed — and chronically food-insecure. “It’s a daily struggle to stay sober and stay healthy and find healthy friends that will help me; those are few and far between,” he reports.

Not alone

LeBlanc isn’t the only WNC veteran who’s fighting to get enough to eat. According to Feeding America, 20 percent of the more than 46 million people who access the organization’s national network of food banks each year are part of households that include someone who’s served or is serving in the U.S. military.

And a 2015 Cambridge University study that surveyed U.S. military veterans who’d served in Iraq and Afghanistan since 2001 found that more than 1 in 4 had experienced food insecurity within the past year, and 12% reported “very low food security.” In addition, it noted that food-insecure veterans tend to be single, low income and frequent binge drinkers.

The study also pointed to the need for further documentation of the issue, which has been gaining attention in recent years. In 2018, the Veterans of Foreign Wars organization said it was “alarmed at the number of veterans suffering from what is being called ‘food insecurity,’” according to a story in VFW magazine.

Not surprisingly, numerous studies have shown that hunger is much more prevalent among the homeless and those with mental health and addiction issues — demographics that tend to include large numbers of veterans. According to the National Coalition for Homeless Veterans, 11% of homeless U.S. adults have served in the military, and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development estimates that roughly 40,000 veterans lack a permanent place to live.

Data from the RAND Center for Military Health Policy Research shows that an estimated 31% of those who served in Iraq and Afghanistan have a mental health condition or experienced a traumatic brain injury. And a 2015 report from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration found that 1 in 15 veterans had a substance use disorder.

Although Asheville’s VA Hospital does not collect data on food insecurity, Laura Tugman, assistant chief of mental health services, says the facility does offer case management services for veterans identified as food-insecure. “We work to connect those veterans to community resources to obtain free and low-cost food on a case-by-case basis,” she explains.

Isolation and community

One community resource that’s been a big help to LeBlanc is Bounty & Soul. The Black Mountain-based nonprofit fights food insecurity with several weekly markets hosted by local churches and schools and a mobile program that covers the Swannanoa Valley. All of them offer free fresh produce, meat and other foods to anyone in need, with no restrictions. Although LeBlanc says he’s relied on various local food organizations for survival, Bounty & Soul is the one he leans on the most.

“Sometimes the church food pantries, they don’t give too much to single guys — maybe just a loaf of bread, some cans of green beans,” says LeBlanc. “[Bounty & Soul’s] food boxes are just wonderful. I get fresh vegetables, I get meat, things like that.”

He also emphasizes that the care and attention he’s received since he first turned to the organization last October have helped sustain him. Its multipronged approach works to nourish the whole individual. Besides offering healthy food, the nonprofit aims to create community by hosting free cooking demonstrations, tastings and classes on wellness and nutrition. The markets are lively, friendly affairs that feel more like a block party than a food distribution center. Everyone who enters is greeted warmly with a smile, offered a box and encouraged to shop for whatever they want.

At one recent market, the numerous tables featured heaps of fresh green beans, tomatoes, lettuce and potatoes; coolers held frozen meat and even cases of kombucha, all donated by local grocers, food businesses and farms. This abundance was offered generously and free of charge, with no questions asked. The general mood at these events is undeniably inclusive and uplifting.

“Those people are amazing,” says LeBlanc. “They literally kept me alive over the winter.”

Ali Casparian, Bounty & Soul’s founder and director of programs, is a domestic violence survivor who frequented food pantries herself when she moved to this area several years ago. Lifting people up and educating them about nutrition and self-care, she says, are integral to her holistic approach to combating food insecurity.

“Food may be what gets [people to the nonprofit’s markets], but what keeps them coming back is the community,” she maintains. “Once you get there, you’re made to feel like you belong there; you quickly make friends, and you’re made to feel comfortable. Even if you walk in with a bit of shame or whatever, once you’re there for five minutes, it dissipates.”

In LeBlanc’s case, Bounty & Soul has gone beyond just providing him with food; the group has also tried to help him with some of the other challenges he’s facing. The veteran has fought an ongoing battle with homelessness since moving to Asheville from Boone about four years ago. Intermittent stays at ABCCM’s Veterans Restoration Quarters and the Western Carolina Rescue Ministry, and a brief stint in an East Asheville apartment through the HUD-Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing Program, have been interspersed with bouts of living in the woods, he says.

LeBlanc used to own an old Volvo station wagon, but he says it was stolen last winter. The crippling lack of transportation is exacerbating his food-access problems and sometimes makes it impossible for him to get to and from his many medical appointments.

“Not only does he suffer from PTSD, he struggles with the daily stress of life moment by moment,” notes Casparian. “He is very isolated and lonely without a vehicle.”

In recent months, the veteran says his pain level has been so intense that he’s been unable to work at all. When Xpress last had contact with him, shortly before press time, he was staying at a friend’s house in Old Fort and relying on borrowed vehicles or bummed rides to get to and from his various appointments at the VA and to Bounty & Soul and other local pantries.

Fresh from the farm

Although the primary focus of the Veterans Healing Farm is providing equine therapy and workshops on agriculture, homesteading, sustainability and holistic health, the organization also gives local veterans access to fresh produce.

For the past three years, the Hendersonville farm has partnered with the Asheville VA hospital, hosting free markets every Tuesday during the growing season where both veterans and staff can enjoy freshly picked produce and cut flowers. The philosophy behind these markets is similar to Bounty & Soul’s approach: addressing food shortages while, more importantly, providing emotional support to veterans.

“For some people, it really does make a difference to their weekly grocery situation. But I think it’s an emotional impact more than anything else,” says Nicole Mahshie, who co-founded the farm with her husband, U.S. Air Force veteran John Mahshie. “We don’t sell any of our produce, because we don’t want to compromise the quality of the produce we can bring directly to the veterans. I think there’s an emotional impact of us just being there and smiling. It’s a really happy place.”

Tugman says the hospital’s relationship with the farm helps local veterans in multiple ways. Besides being “excited about the free produce,” she notes, “Access to vegetables supports some of our veterans in achieving their health and wellness goals” established through the Veterans Administration’s Whole Health Coaching program.

And for veterans who are receiving mental health treatment, says Tugman, visits to the farm are a way to learn recovery skills such as healthy eating and cooking strategies while also exploring horticulture therapy. “We’ve received very positive feedback from the veterans who have attended our outings to Veterans Healing Farm,” she reveals.

As this issue went to press, LeBlanc was working toward having surgery through the Veterans Choice Program to repair the bulging discs in his spine — and he says the prognosis is good. Once he’s had the surgery and is freed from chronic pain, the former home renovation contractor hopes to figure out reliable transportation, find a job and rebuild his life. “The goal is to get back to work again,” he emphasizes.

Casparian laments the fact that some veterans must struggle to meet basic needs like food, shelter and health care, but she points to a silver lining in LeBlanc’s case. “The light in this is that a community is coming together to do what they can to help just one of those veterans, and I think that is powerful. We need to do more; we all need to do more for our veterans.”

For more on Bounty & Soul, visit bountyandsoul.org or call 828-419-0533. Learn more about the Veterans Healing Farm at veteranshealingfarm.org or call 800-273-8255.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.