George Orwell once said that Nineteen Eighty-Four “wouldn’t have been so gloomy if I had not been so ill”. But the truth is that Orwell, along with many other writers, found plenty to be gloomy about in postwar Britain. As he wrote in one of his London Letters in the New York magazine Partisan Review: “No thoughtful person I know has any hopeful picture of the future.” He was magnifying a widespread sense of bomb-haunted unease rather than projecting on to the world some private torment.

Amid the postwar malaise, Orwell’s friends thought he looked even more gaunt and run-down than usual. His wife, Eileen, had died during a hysterectomy in 1945 and he desperately needed a change. For years, he had dreamed of squirrelling himself away on a Hebridean island; the well-connected Observer editor David Astor recommended Jura in the Inner Hebrides, which had fewer than 300 inhabitants. Robin Fletcher, the laird of Jura, and his wife, Margaret, owned a remote farmhouse, Barnhill, that needed a tenant to save it from ruin. It sounded ideal. Orwell and his sister Avril left London for Jura in May 1946.

Jura is where the myth of Nineteen Eighty-Four takes hold: the compelling image of a sad, sick man who incarcerated himself on a godforsaken rock in a shivering sea and, in a state of agonising despair about his future and the world’s, wrote the book that killed him. Among other things, that cliche does a disservice to Jura, which has a temperate climate and a raw, startling beauty. Situated at the north end of the island, Barnhill was certainly remote. The house had no telephone or postal service. Supplies of water and fuel were unreliable. The closest hospital was in Glasgow: a taxi, two boats, a bus and a train ride away. Nonetheless, Orwell loved it, especially after his housekeeper, Susan Watson, arrived with his son, Richard. Jura offered the life that Eileen had prescribed in her final letters to her husband: fresh air, family and fiction.

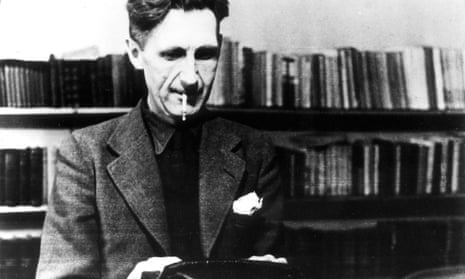

The impression you get from Orwell’s letters and diaries was that he relished his new son-of-the-soil routine, planting fruit trees and vegetables, shooting rabbits, raising geese and fishing for mackerel, pollock and lobster. Having no desire to live like a hermit, he extended invitations to many of his friends and formed a friendship with Fletcher, his landlord. As for the novel he had been dying to crack on with, freed from the treadmill of journalism, Orwell found he didn’t want to write much at all. However, by the end of September, he had begun work on Nineteen Eighty-Four. When he was feeling well, he worked in the sitting room; otherwise, he typed in bed in his dressing gown in a room fogged by cigarette smoke and paraffin fumes.

Orwell returned to London for the winter of 1946-1947, which brought a windfall from the publication in America of Animal Farm and an onslaught of heavy snow and Siberian temperatures, with the capital actually colder than Jura. Orwell later traced his final period of ill health back to that winter’s assault on his lungs. You get a flavour of his last “unendurable” winter in broken-backed, bombed-out London in the opening chapters of Nineteen Eighty-Four: the power cuts, the economy drives, the patchwork buildings, the blunt razor blades, the bad food, the clothing coupons, the cairns of rubble, the grit in the air.

It was April when he arrived back on Jura with Avril and Richard, just as the snow was melting and spring was nudging through. The garden at Barnhill was buttery with daffodils. By the end of May, he had written about a third of his novel, even if it was “a ghastly mess”, as he told his publisher, Fredric Warburg, in his typically self-effacing way. Orwell’s health worsened in the autumn, kiboshing an optimistic plan to report on life in the American South and an Observer commission to spend three months in Kenya and South Africa. He wasn’t going anywhere. He’d been ill all year and losing weight but “like a fool” decided to press on with his novel instead of seeing a doctor who, he suspected, would force him to down tools.

He finished the first draft of Nineteen Eighty-Four in bed on 7 November. Shortly before Christmas, he succumbed to medical advice, travelling to Hairmyres hospital in East Kilbride, near Glasgow, to seek treatment. He would not be able to return to Jura, or his novel, for another seven months. At that point, he later admitted to his friend Celia Paget: “I really felt as though I were finished.” At Hairmyres, he was diagnosed with chronic fibrotic tuberculosis in the upper part of both lungs.

Orwell was discharged on 28 July. Avril thought he could have made a full recovery if he had moved to a sanatorium but the siren song of the novel was too powerful so he returned to Jura and rewrote it line by line. His recovery passed with the summer and his health spiralled down again dramatically in the autumn.

Did he wreck his health beyond repair for want of a typist? Warburg thought so. When Orwell finished the final draft in November, he asked Warburg to find him someone who could come to Barnhill to retype the manuscript, which was a mess of scribbles. But no typist could be found in a hurry and Orwell was impatient. He typed it himself at the punishing rate of around 4,000 words a day, seven days a week, propped up in bed for as long as he could bear in between bouts of fever and bloody coughing fits. In the first week of December, he typed the final words, came downstairs, finished the last bottle of wine in the house, then went back to bed, demolished by his efforts.

On 2 January 1949, Orwell left Barnhill for the last time to make the long journey to the Cotswold sanatorium in Cranham, Gloucestershire. It pained him to leave somewhere so full of life. As he glumly told Astor, editor of at the Observer: “Everything is flourishing here except me.”

It is fortunate that the manuscript didn’t require rewriting because Orwell was incapable of such work. It was all he could do to examine the proofs that arrived at Cranham during February and March and draw up lists of friends and contemporaries who should receive advance copies, including Aldous Huxley and Henry Miller.

He suggested to Warburg that Bertrand Russell might be willing to write a blurb, which indeed he was. It is unlikely that he would have approved had he known that his American publisher Harcourt, Brace had sought a back-cover endorsement from J Edgar Hoover, the red-baiting director of the FBI. Hoover declined the request and instead opened a file on Orwell.

Orwell was rarely short of company at Cranham. As well as the usual suspects – Warburg, Malcolm Muggeridge, Anthony Powell, Cyril Connolly – he was visited by Evelyn Waugh, whose opinions he found “untenable”, and a rather taxing interviewer from the Evening Standard, Charles Curran, who wore him out by arguing about politics. His most frequent and exciting well-wisher was 29-year-old Sonia Brownell, Connolly’s famously desirable Horizon protege, who began visiting him in May.

Orwell’s greatest sadness was missing Richard; terrified of infecting his son, he kept the boy away for long stretches. He asked Warburg to arrange a second opinion that would tell him honestly how much time he had left. Warburg’s friend Dr Andrew Morland, a Harley Street specialist, told Orwell that if he wanted to survive, he would have to avoid work for at least a year. This was painful news for this most industrious of writers, leaving him nothing to do but read, solve crossword puzzles and write letters that crackled with the wit, gossip and analysis that had nowhere else to go.

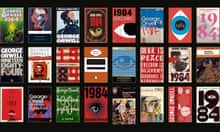

Nineteen Eighty-Four was published by Secker & Warburg on 8 June 1949. The critical reaction was overwhelmingly positive, with the New York Times Book Review reporting “cries of terror rising above the applause” and comparing the “state of nerves” to the uproar over Orson Welles’s [radio adaptation of] The War of the Worlds. The book was variously compared to an earthquake, a bundle of dynamite and the label on a bottle of poison. “I read it with such cold shivers I haven’t had since as a child I read Swift about the Yahoos,” John Dos Passos wrote to Orwell, confessing that he’d had nightmares about the telescreen. For EM Forster, it was “too terrible a novel to be read straight through”.

Warburg visited Orwell at Cranham a week later and wrote a sobering report on his “shocking” condition. Nonetheless, in July Orwell proposed to Sonia, who said yes. Some of his friends found the idea ghoulish. “Orwell was totally unfit to marry anyone,” said Astor. “He was scarcely alive.” Muggeridge thought the marriage “slightly macabre and incomprehensible”. But Orwell firmly believed that it would give him something to live for. As Winston says of Julia in Nineteen Eighty-Four: “Her body seemed to be pouring some of its youth and vigour into his.”

Nobody thought that Sonia truly loved him. Some who knew her said that she was a ruthless woman who married him for the money and prestige because Horizon was running on fumes and she would soon lose her job. Others thought it was an act of chivalrous self-sacrifice, motivated by pity and respect. It is likely that Orwell and Sonia’s motives overlapped: he needed her and she needed to be needed.

On 2 September, Orwell moved from Cranham to a private room at University College Hospital in London. Friends doubted he would ever leave. It is very possible that he was already beyond repair when, on 13 October, he married Sonia in his hospital room, in front of just half a dozen guests. Astor was reminded of Gandhi – “skin and bone”. The wedding lunch took place at the Ritz minus the groom.

Orwell’s health and mood were revitalised by marriage – he said he had five more books in mind and couldn’t die until he’d written them – but not for long. He still enjoyed talking about books and politics but increasingly he was drawn back into the past, reminiscing about Eton, Burma, Spain and the Home Guard in a way his friends had never heard before. Dropping in on Christmas Day, Muggeridge saw in Orwell’s face no sense of acceptance or peace: “There was a kind of rage in his expression, as though the approach of death made him furious.”

Orwell and Sonia made plans to move to a sanatorium at Montana-Vermala in the Swiss Alps. An air ambulance was booked for 25 January 1950, with the painter Lucian Freud, Sonia’s close friend, to join them as a kind of nurse. Orwell asked for his fishing rod to be delivered to University College Hospital, with a view to fishing in Alpine lakes. It was propped up in the corner of his room in the early hours of 21 January when a blood vessel in his lung ruptured and he rapidly bled to death.

Muggeridge arranged the funeral at Christ Church in Albany Street in Camden, north London, where the mourners came from every corner of Orwell’s peculiarly compartmentalised life – from Eton, Spain, the BBC, the Home Guard, Tribune, literary London, the European diaspora, the streets of Islington and the social circles of his two wives. Though an atheist, Orwell was enough of a traditionalist to want to be buried in a country churchyard and Astor pulled strings for the last time to secure a plot at All Saints’ church, Sutton Courtenay in Berkshire.

Only he and Sonia were present when Orwell’s body was lowered into the ground, to lie beneath a typically matter-of-fact headstone, bearing just his name and dates. The name was still Eric Arthur Blair. He never did get around to changing it. Orwell’s life had overlapped with the public life of his final novel for just 227 days.