Even before you step foot into Morgan Meyers’ Riverton home, it’s clear toddlers live here.

Toys in bright primary colors line the front porch, and little hand and fingerprints coat the glass front door. The fingerprints belong to Landon, Meyers’ 4-year-old son, and Elise, her 3-year-old daughter.

The home tells the same story as you enter. The front room’s focal point isn’t a television or fireplace — it’s a large children’s tent in the shape of a shark. Meyers says her kids have been on a “Baby Shark” kick recently, and their grandfather insisted on the tent.

“There’s a lot of fun to it,” Meyers said about parenting two toddlers so close in age. “But it is hectic and crazy and a little …”

She pauses, looking for the right words to describe it. “You kind of feel like you’re living in a tornado.”

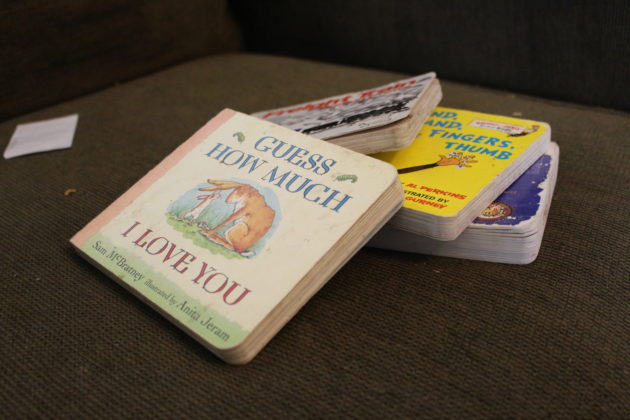

Scattered books crowd the home’s main level — under the couch, in the tent, on the kitchen floor. They’re part of the Meyers’ extensive book collection. Next to one pile of books lies a blue plastic bowl with an uneaten chicken nugget, and the stairs to the basement are lined with plastic Easter eggs.

While her kids nap, Meyers talks about the intentional nature of her parenting. The books and toys aren’t just part of a mess — they’re part of Meyers’ effort to limit her kids’ screen time. She worries about the effects of screen time on her children’s development, even if sometimes it’s easier to plop them down in front of the TV.

“I think I struggle with the balance,” Meyers admitted. “It’s, ‘This is good. It’s encouraging good things. It’s educational. It’s good for my mental health, to be totally honest.’ But at what point is it no longer good? You have to find that balance and say, ‘OK, do you know what? We’re done. We are done.’”

Like Meyers, parents around the country are struggling to find and maintain the right screen time balance in an age when tablets, mobile phones and televisions dominate. A 2017 Common Sense Media report found 98% of American children 8 and under live in a home with a mobile device, and mobile media time tripled between 2011 and 2017.

The majority of U.S. children spend significantly more time in front of screens than recommended, incurring potentially negative effects on their development, relationships and behavior, along with long-term side effects that are still unknown.

Parents can avoid these negative side effects, however, and help their children build healthy, beneficial relationships with media by changing a few key screen time habits, according to experts.

Minimizing screen time

The American Academy of Pediatrics released updated screen time recommendations in 2016, which include avoiding screen media altogether for children younger than 18 months and limiting screen use to one hour per day in children ages 2 to 5 years. When children do watch media, the academy adds, it should be high-quality programming they co-view with their parents.

However, these recommendations aren’t currently a reality among American parents, at least on average.

A February JAMA Pediatrics study found daily screen time for children 2 and under averaged about 3 hours per day in 2014, a significant increase from the 1997 average of 1.3 hours a day for the same age group. Children ages 3 to 5 didn’t have a significant change between 1997 and 2014 — during both years, they averaged almost 2.5 hours a day.

Dr. Yolanda Reid, lead author of the American Academy of Pediatrics technical report “Children and Adolescents and Digital Media,” said the academy’s recommendations come down to concerns about brain development and the displacement of other important developmental activities.

“I think parents may worry, ‘Gee, should I get my child started on digital media, on screens, on games, on ebooks … when they’re younger so they don’t fall behind?’” Reid said. “But the good news is that these media are so user friendly that your child will not fall behind. What we really care about in those first 18 to 24 months of life is … (that) this is a time of great brain development, and we want to maximize that.”

Reid recommended all parents use the academy’s media time calculator and tool to create a personalized family media plan. She said the tool can give families an idea of what they need to do each day and then gauge what time is left for entertainment media.

When children spend time getting sufficient sleep, physical activity, real-world social contacts and complete schoolwork when applicable, according to Reid, there is rarely leftover time to spend using digital media.

“We don’t want screen time to to displace healthier activities,” Reid said. “That’s the bottom line.”

When screen time does displace the important activities in a child’s daily schedule, Reid said, that’s when side-effects and physical risks come into play, including a sedentary lifestyle, an increased obesity risk and sleep problems.

However, Reid acknowledged the discrepancy between recommendations and reality. She said she understands that sometimes, parents will use screens more than recommended or use them as babysitters.

“We don’t want parents to feel guilty. We want parents to try to maximize the positive time they spend with their children and minimize the use of screen media as a babysitter, as a distractor, and recognize that there will be times where everybody kind of does this,” she said. “But the more you minimize it, the more you interact with your child, even at less than one year, the more you’ll be promoting their neurological and social and language development.”

Screen time and early development

As a busy mother of two toddlers, Meyers admits that, almost any day, she’d rather just turn on the TV or a video game to keep her children entertained rather than dealing with the mess and hassle of legos, books or crayons. But she also recognizes her kids act like “little robots” when they’ve spent too much time in front of a screen.

“When you’re forcing them to be reading books, to be playing hands-on with Legos, to be physically in their environment, physically interacting, they become a little bit more human,” she said. “You get to see their personalities coming out, because they’re not just sitting there glued to the screen that’s telling them what to think and say and do and be. They’re becoming their own little humans.”

The crucial development that takes place during children’s early years — when, in Meyers’ words, they become their own little humans — happens when children interact with their environments and learn from their experiences, according to BYU human development professor Alex Jensen.

These learning opportunities can’t be replicated by screens; in fact, screens often displace them.

Jensen said, for example, that young children develop their language by listening to and interacting with other people talk, and they develop cognitively by learning hands-on about sizes and shapes.

“It’s just teaching them all these things that are really foundational for all sorts of development later on, and when they’re spending a lot of time with screens, they are not doing those things,” Jensen said. “It’s not that they can’t learn them later, but they’re really driven at that age to be doing those things.”

The World Health Organization recommended in its 2019 report “Guidelines on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior and Sleep” that children should have no sedentary screen time until they’re 2 years old. For 2 to 4-year-olds, the report says, sedentary screen time shouldn’t exceed an hour a day, but “less is better.”

Dr. Juana Willumsen, the WHO focal point for childhood obesity and physical activity, said the organization made these specific screen time recommendations while considering screen time as a sedentary activity. She said the evidence points to screen time’s unfavorable effects on motor and cognitive development.

“That is what the recommendations really call for, to make sure that children within their day are not only physically active, but in the time that they are sedentary, that they’re having those quality interactions that are so important for language development, emotional, psychosocial development, and especially in these young children who are learning so, so, so fast at this age,” Willumsen said.

For children under 2, Willumsen said WHO found no health benefits for sedentary screen time. It’s a time when language development is key, she said, and screen time at that age is associated with cognitive development issues.

Behavior & relationships

For Bronte Burgess, a mother of two living in Arizona, breaking the screen time habit for young children is like giving birth: right when it seems like things are overwhelmingly difficult, she said, they start to get better.

“That’s kind of how it is with a lot of hard things,” Burgess said. “You’ll reach a breaking point where you’re like, ‘I can’t do this any longer.’ But right after that is when things get better and resolve themselves.”

Burgess knows firsthand both the difficulty and satisfaction that comes with helping children break their screen time habits. She was careful with screen time when her 5-year-old daughter was an only child, but that changed when she became pregnant with her son, who’s now 3. Balancing pregnancy and a recent move made life difficult, and daily, frequent screen time became a habit.

“(My daughter) would get up in the morning, and she knew how to turn the TV on by herself, and she’d turn on her own show and just watch TV for a little bit while I was getting ready,” Burgess said. “But I noticed on the days that we did that, she would be super crazy. She’d get angry a lot faster about different stuff.”

After noticing how TV time negatively affected her daughter’s behavior, Burgess decided to try going without it for just one week. The transition was rough at first — perhaps why Burgess compared it to childbirth — but her daughter’s behavior started to improve almost immediately, and Burgess decided to cut down on screen time for good.

“At first, she would whine about it and constantly ask for me to turn the TV on … and it was probably even more contentious and disconnected for that little bit when we were transitioning,” Burgess said. “But now I feel like it’s a lot better. … She’s playing with her little brother a lot better. She’s super helpful to me, which is awesome, and I just feel like we feel more connected.”

Like Burgess witnessed firsthand, screen time doesn’t just have consequences for a child’s development — it can also impact both their behavior and relationships.

An April 2019 study published in PLOS One concluded that increased screen time among preschoolers is associated with worse inattention problems, and a separate study conducted among Iranian children and adolescents found prolonged leisure time spent using screens is associated with violent and aggressive behavior.

Kendall Lee, who teaches second grade at Blackridge Elementary in Herriman, said she can tell which of her students have screen time in moderation by their behavior.

“The social maturity and their ability to communicate and interact with others is totally different,” Lee said. “Their attention spans are higher just interacting through lessons, and they don’t need to be constantly stimulated by a game or a video.”

BYU family life professor Dr. Sarah Coyne studies media’s impact on children and families. She said watching pro-social behavior in media can lead to more empathy, pro-social behavior, and less aggression for adults, adolescents and children. Media can also strengthen relationships when parents co-play or co-view with their children, Coyne said.

However, media use also has potentially negative effects for children’s behavior and relationships, the most serious of which is media addiction. Coyne is currently working on a paper about the age in which media addiction develops in light of recent research that shows problematic media use in children as young as 4 years old. This problematic media use creates conflict in the family and home.

“It’s hard to be addicted to things at age 4,” Coyne said. “But it’s like, if I try to take away media, there’s a significant tantrum, the child is fixated on media, asks for media all the time, they’re trying to sneak media, they’re lying about it to their parents, it’s causing a lot of conflict in that relationship. So we kind of see that appear around age 4.”

Coyne’s research will find the root of media addiction early in childhood and map it over time.

Listen to the full interview with Dr. Sarah Coyne below.

The right kind of screen time

The first two weeks of preschool for 3.5-year-old Savannah Jordan were all about apples. She sang and read a poem about apples, read books about apples, sorted apples, made apple stamps, compared apples, rolled apples down ramps, did apple crafts and, of course, ate applesauce.

Hannahrose Jordan, Savannah’s mother, explained the apples curriculum as part of a preschool homeschool program, Playing Preschool, that the family recently started. Jordan described Playing Preschool as a hands-on program that teaches real-life skills.

“It’s really fun,” Jordan said. “It’s not something that (my daughter) thinks is hard or that it’s boring. It’s always fun to learn, and every day she’s super excited about school.”

Education is a priority for Jordan, who lives in Connecticut with her family. This emphasis also reflects in how she manages her daughter’s screen time. Jordan does research to find the most educational programs and games possible and strives to co-view with her daughter, explaining and discussing what’s happening on the screen.

“I have found if I do want to share something with Savannah, it will help her learn, and it will help her be more engaged and not get so sucked into the screen if I am sitting there with her and interacting with her while she’s watching the show,” Jordan said.

Like Jordan has learned, there’s a right way and a wrong way to do screen time. Media use is far less detrimental to children when screens are used it in moderation and alongside a parent or caregiver. High-quality, educational programming that teaches pro-social behaviors is best.

Reid warned that many TV shows, apps and video games claim to be educational in their marketing, but may not be in practice.

“They have a lot of bells and whistles which can be distracting to young children and to parents, and they’re often constructed to keep people using them more than would be ideal,” she said.

Reid said some helpful resources in helping parents choose educational, high-quality content include Common Sense Media, articles posted by the American Association of Pediatrics and, for video games, the Entertainment Software Rating Board.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends minimizing the amount of violence and aggression children watch in media, according to Reid, and has typically promoted programs like Sesame Street or PBS products. She said parents should always watch or play media before sharing them with their children, and then, parents and children should co-watch or co-play the media together.

Jensen said there are a number of emotional benefits in terms of perspective taking, pro-social behavior and empathy when parents co-watch programs with their children and explain what’s going on.

“If you’re gonna have your kid, let’s say watch TV for an hour a day … ideally, you’re sitting down with them and you’re watching that show,” Jensen said. “And as things happen in the show, as a parent, then you’re doing this mental state talk where you’re implying or verbally implying what the characters thinking.”

However, despite the benefits when screen time is done correctly with older children, Jensen said it’s unlikely media have any educational benefits for infants and toddlers. Children can only understand content on a broader scale when they reach middle childhood between the ages of 7 and 10.

Toddlers can’t follow the storyline of a TV show even lasting 15 to 20 minutes, Jensen said. He added they may be able to learn things like shapes and colors through games or TV shows, but that’s rarely the best option in terms of education.

“They don’t need a screen to learn shapes,” Jensen said. “In fact, they’re probably going to learn shapes better holding blocks of those shapes and actually physically touching them than just looking at the screen.”

‘Just a little differently’

Although there are plenty of unknowns when it comes to long-term effects of screen time, this much is clear: children are using screens a lot more than they should, and some of the potential effects are worrisome.

This comes as no surprise to Morgan Meyers, who said she’s no stranger to “mom guilt” when it comes to screen time. She tries her best to help her children have a healthy media diet. But especially in the winter, she said, it’s hard to keep screen time at a minimum.

“There have been days where I put the kids to bed and I’m like, ‘I don’t know that the kids did anything but watch TV today. Awesome,’” Meyers said.

Many parents like Meyers feel high levels of guilt around their kids using media, according to Coyne. But what parents need, Coyne said, is just a little more balance and more media co-use with parents.

“Cutting ourselves just a little slack, I think, is OK too,” Coyne said. “Find that balance, go by the guidelines as much as humanly possible, and you’ll be OK.”

There are several small changes a parent can make to find a screen time balance, according to Reid, but one of the most important is that parents become aware of their own media use examples.

“The reality is that we, as parents, are role models for children,” Reid said. “Digital media are made to attract us and keep us engaged and involved, and we’re susceptible as adults to that as much as children are, whether we want to admit it or not. We have to be aware of our own digital media use and behaviors.”

Reid said she recognizes that parents need breaks, and when possible, it’s better to have friends and family trade off watching children instead of plopping them down in front of a TV. But realistically, that’s not always possible, and she doesn’t want parents feeling guilty.

For Meyers, it simply comes down to being better every day and recognizing when things need to change.

“Sometimes I look at my priorities, reevaluate and say, ‘Ooh, we could do a little bit better tomorrow. Let’s do things just a little differently,’” Meyers said. “And maybe it’s time to cut back. Let’s see how we can do a little better tomorrow.”