- News

- City News

- bengaluru News

- Ola & Uber revolutionised transport in Bengaluru; but congest city roads & hit use of mass transport

Trending

This story is from July 15, 2019

Ola & Uber revolutionised transport in Bengaluru; but congest city roads & hit use of mass transport

NO-GO ZONE: Around 1,500 cabbies with Ola and Uber line up their vehicles outside Freedom Park as part of a protest in this file photograph from February 3, 2017. Strikes that month, over poor earnings by drivers affiliated to the two cab aggregators, led to a reduction in traffic congestion in Bengaluru.

BENGALURU: When Ola and Uber rolled into Bengaluru in 2012-13, they promised to solve the city’s traffic problems by reducing personal car ownership through ridesharing. With efficient and hasslefree services, these app-based cab aggregators revolutionised the way Bengaluru travels. But they also increased traffic congestion in a city that is now notorious for the problem.

The companies also appear to have reduced the use of public transport, by taking passengers from bus services.An increase in the number of people who choose to use cabs instead of buses only increases the use of cars, especially when most cabs ferry single passengers, experts say. To make matters worse, many cab drivers park on the roadside, some in congested areas, shrinking carriageway width as they wait for their next trip requests.

While no comparable study has been carried out in Bengaluru, a recent study by the San Francisco County Transportation Authority (SFCTA) found that traffic congestion in San Francisco surged by 60% between 2010 and 2016, and that Uber and Lyft were responsible for more than half of that rise.

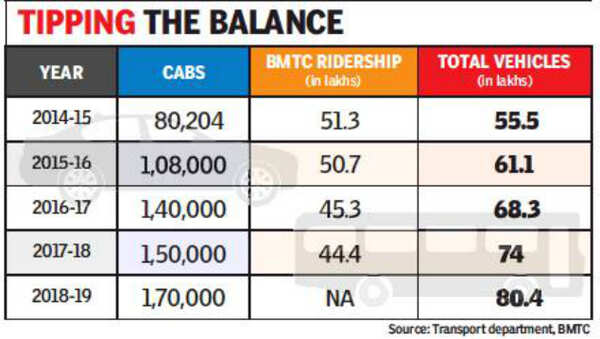

These app-based aggregators are primarily responsible for a huge jump in the number of cabs in the city, from 66,264 in 2013-14 and 1.7 lakh in 2018-19. Cab aggregators maintain that their business models encourage ridesharing, but many passengers who would have otherwise taken buses or autorickshaws, or cycle or walk to closer locations, now prefer cabs, taking up more space on an already crowded road network. Single-occupant cabs flood areas such as the central business district (CBD), particularly during peak hours.

The transport department and traffic police are yet to conduct a study on the impact that Ola and Uber have had on traffic in Bengaluru and the two companies often refuse to share data with government agencies, usually citing potential misuse by competitors.

Just how much they have contributed to the increase in congestion was evident in February 2017, when most cabbies stayed off the roads to protest dwindling earnings. There was a visible decrease in vehicles on the city’s roads and BMTC’s occupancy rate increased, especially in AC buses in the tech corridors of ITPL and Electronics City.

The two companies do offer carpooling services like Ola Share and UberPool but they have only taken away bus and autorickshaw passengers, experts say. That assertion is bolstered by a decline in ridership for BMTC, from 51.3 lakh in 2014-15 to 44.4 lakh in 2017-18 — the lowest in a decade despite adding services — even if Namma Metro also contributed to the drop.

For many commuters, however, app-based cabs have become indispensable. “I’ve stopped taking buses and autos after the entry of Ola and Uber,” said M Lakshmi, who regularly uses cabs. “UberPool and Ola Share are cheaper than BMTC Volvo buses and have less waiting time. They are also faster than buses since they take passengers directly to their destinations.”

NV Prasad, BMTC managing director, said he wasn’t aware of the impact of app-based aggregators on BMTC. “I haven’t come across any study,” he said.

While the government has placed a cap on auto numbers, it hasn’t set any limits on registration of new cabs. Transport commissioner VP Ikkeri said there is no framework to put a cap on taxis. “We’re aware that the number of cabs in the city is high but we haven’t taken any decision to cap their numbers like we do with autorickshaws,” he said. “We’re also waiting for Centre to take a decision on carpooling.”

Bengaluru Bus Prayanikara Vedike member Vinay Srinivasa said app-based aggregators are actually competing with public transport not complementing it. “Private carpooling among individuals may reduce congestion but cab aggregators only increase the number of vehicles on the city’s roads and reduce patronage of public transport,” he said. “It’s unfortunate that the government has not conducted any study on the impact of these cab companies.”

Additional commissioner of police (traffic) P Harishekaran said they have received several complaints about illegally parked cabs. “We recently called a meeting with cab aggregators and asked them to designate parking space for cabs to prevent illegal parking, especially in residential areas at night,” he said.

Industry sources, however, say a larger number of cabs is not the only reason that traffic congestion has increased. A booming population, rise in average income allowing individuals to purchase more than one car, poor infrastructure, inefficient public transport and lack of parking space are also major factors at play, they say.

The companies also appear to have reduced the use of public transport, by taking passengers from bus services.An increase in the number of people who choose to use cabs instead of buses only increases the use of cars, especially when most cabs ferry single passengers, experts say. To make matters worse, many cab drivers park on the roadside, some in congested areas, shrinking carriageway width as they wait for their next trip requests.

While no comparable study has been carried out in Bengaluru, a recent study by the San Francisco County Transportation Authority (SFCTA) found that traffic congestion in San Francisco surged by 60% between 2010 and 2016, and that Uber and Lyft were responsible for more than half of that rise.

When contacted, both Uber and Ola refused to comment.

These app-based aggregators are primarily responsible for a huge jump in the number of cabs in the city, from 66,264 in 2013-14 and 1.7 lakh in 2018-19. Cab aggregators maintain that their business models encourage ridesharing, but many passengers who would have otherwise taken buses or autorickshaws, or cycle or walk to closer locations, now prefer cabs, taking up more space on an already crowded road network. Single-occupant cabs flood areas such as the central business district (CBD), particularly during peak hours.

The transport department and traffic police are yet to conduct a study on the impact that Ola and Uber have had on traffic in Bengaluru and the two companies often refuse to share data with government agencies, usually citing potential misuse by competitors.

Just how much they have contributed to the increase in congestion was evident in February 2017, when most cabbies stayed off the roads to protest dwindling earnings. There was a visible decrease in vehicles on the city’s roads and BMTC’s occupancy rate increased, especially in AC buses in the tech corridors of ITPL and Electronics City.

The two companies do offer carpooling services like Ola Share and UberPool but they have only taken away bus and autorickshaw passengers, experts say. That assertion is bolstered by a decline in ridership for BMTC, from 51.3 lakh in 2014-15 to 44.4 lakh in 2017-18 — the lowest in a decade despite adding services — even if Namma Metro also contributed to the drop.

For many commuters, however, app-based cabs have become indispensable. “I’ve stopped taking buses and autos after the entry of Ola and Uber,” said M Lakshmi, who regularly uses cabs. “UberPool and Ola Share are cheaper than BMTC Volvo buses and have less waiting time. They are also faster than buses since they take passengers directly to their destinations.”

NV Prasad, BMTC managing director, said he wasn’t aware of the impact of app-based aggregators on BMTC. “I haven’t come across any study,” he said.

While the government has placed a cap on auto numbers, it hasn’t set any limits on registration of new cabs. Transport commissioner VP Ikkeri said there is no framework to put a cap on taxis. “We’re aware that the number of cabs in the city is high but we haven’t taken any decision to cap their numbers like we do with autorickshaws,” he said. “We’re also waiting for Centre to take a decision on carpooling.”

Bengaluru Bus Prayanikara Vedike member Vinay Srinivasa said app-based aggregators are actually competing with public transport not complementing it. “Private carpooling among individuals may reduce congestion but cab aggregators only increase the number of vehicles on the city’s roads and reduce patronage of public transport,” he said. “It’s unfortunate that the government has not conducted any study on the impact of these cab companies.”

Additional commissioner of police (traffic) P Harishekaran said they have received several complaints about illegally parked cabs. “We recently called a meeting with cab aggregators and asked them to designate parking space for cabs to prevent illegal parking, especially in residential areas at night,” he said.

Industry sources, however, say a larger number of cabs is not the only reason that traffic congestion has increased. A booming population, rise in average income allowing individuals to purchase more than one car, poor infrastructure, inefficient public transport and lack of parking space are also major factors at play, they say.

End of Article

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA