Op-Ed: Breaking U.S. immigration laws saved lives in 1975. It gets you arrested today

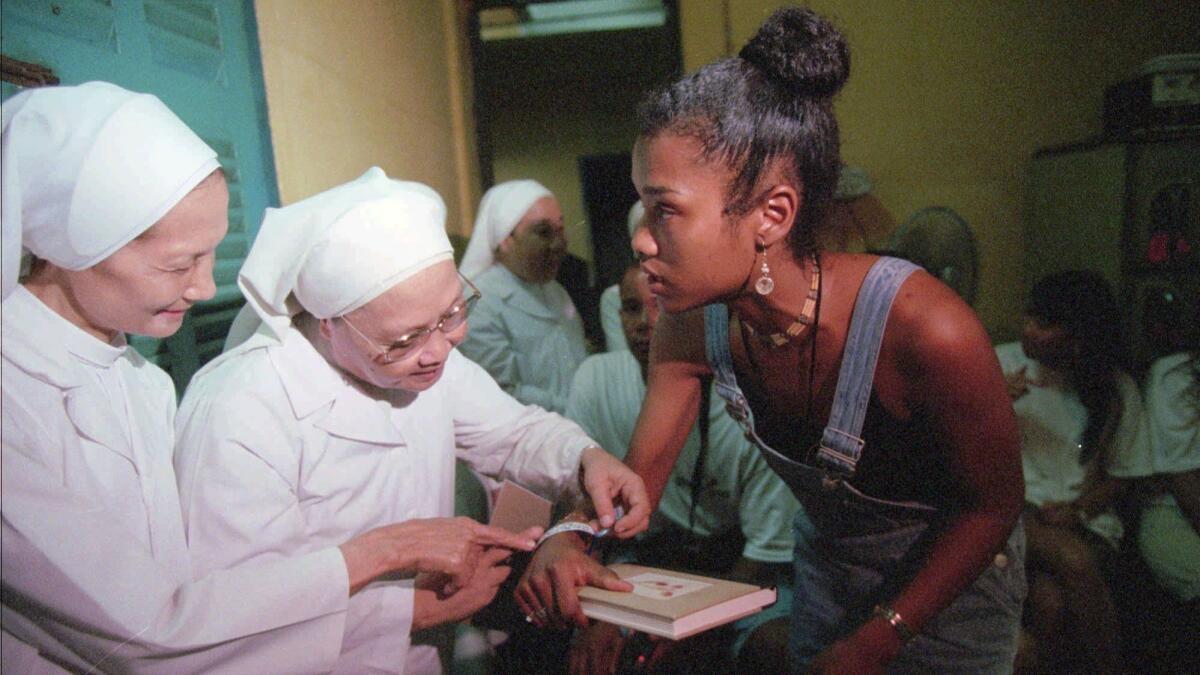

As the Vietnam War caromed to an end, Sister Marie Therese LeBlanc, a middle-aged American nun serving at Friends of the Children of Vietnam orphanage in Saigon, signed one affidavit after another attesting to sons and daughters she never had. It was April 23, 1975, one week before the city fell to the communists.

The 36 people LeBlanc claimed as her children were the adult employees of her orphanage and their families. Nevertheless, State Department officials at the evacuation processing center at Tan Son Nhut air base affixed their consular seals to her affidavits, and American airmen added the names she provided to the flight manifests of the Air Force transports flying out of Saigon. They collaborated with her because they knew, as she did, that the North Vietnamese had threatened retribution against anyone with ties to the losing side in the war.

A nun, U.S. diplomats, military officers and dozens of others followed the dictates of conscience, not the law, in April 1975. They lied and broke explicit rules to save Vietnamese lives. None were prosecuted. If their counterparts at our southern border repeated such acts today, they could easily face imprisonment.

Smith’s mimeographed form contributed to the largest humanitarian operation in U.S. history.

LeBlanc exploited a loophole created by U.S. Defense Attache Maj. Gen. Homer Smith. Ambassador Graham Martin was under pressure from Washington to evacuate Americans from South Vietnam before the bloodbath began. Many of those whom officials wanted out were civilian contractors who had Vietnamese wives and children and refused to leave without their wives’ extended families. On April 19, the Immigration and Naturalization Service had sent Martin a cable: To expedite the evacuation of U.S. citizens, any American could sponsor visas for their Vietnamese in-laws if they agreed to be responsible for the cost of their transportation, care and resettlement.

Smith seized on the option. He composed an “affidavit of support” that would permit Americans to sponsor anyone they claimed as a family member. Martin, who wanted Washington off his back, reluctantly agreed to the affidavit, and his secretary mimeographed copies that quickly circulated through the contractor community and beyond.

Smith knew the affidavits would proliferate. He told his staff members they could list anyone they wanted to evacuate as dependents, provided that none were in the South Vietnamese military. Teenager Linh Duy Vo later credited Smith for his escape to the United States, writing in a tribute after Smith’s death in 2011, “You had saved thousands of lives, a repeat of Schindler’s list. I was among them.” Others made a similar comparison. Jackie Bong, who got out of the country with the assistance of an American posing as her husband, later wrote that her escape was like “Jews being helped to flee Europe during World War II.”

Smith’s mimeographed form contributed to the largest humanitarian operation in U.S. history. On April 21, the U.S. Air Force evacuated 249 Americans and 334 “others,” mostly Vietnamese, from Saigon. The next day it flew out 550 Americans and 2,801 others, and on April 23, LeBlanc’s “children” were among the 5,574 others. By the end of April, the Air Force had evacuated 45,000 South Vietnamese and third-country nationals. Add those to the evacuees rescued by the U.S. Navy at sea, and in the last weeks of the war, 130,810 refugees got out of Indochina with U.S. aid.

There were many American Schindlers. Bill Ryder, an official with the U.S. Military Sealift Command, encouraged the captain of an American freighter to defy orders to leave Saigon with an empty vessel. Under cover of darkness, evacuees boarded the ship, and after reaching international waters the captain announced that he was carrying 700 stowaways. Ryder understood that he was breaking American, Philippine and South Vietnamese visa and passport laws, using a ship chartered by the U.S. Navy at a cost of $12,000 a day, and sticking American taxpayers with the bill.

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute »

Lionel Rosenblatt and Craig Johnstone, Foreign Service officers who had worked in Vietnam, were just as willing to take a risk. They went AWOL from their State Department desk jobs in Washington, flew to Saigon and worked undercover to evade embassy security officers who had been ordered to find and expel them. They helped more than 500 of their Vietnamese friends and former co-workers and family members get to Tan Son Nhut and onto evacuation flights. They were summoned to Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s office later. Kissinger, once a German refugee himself, told them, “You did a very admirable thing, I’m very proud of you.” Turning to the official responsible for bringing them to his office, he said, “If I get another memorandum … chastising the only people who have done the honorable thing, it’ll be you who’ll be dismissed.”

Four decades later, that forbearance is AWOL in the United States. In January 2018, a volunteer with a humanitarian organization was charged with a felony for providing food and water to two migrants who had crossed into a desert wildlife refuge where 32 people had perished during the previous year. A year later, four humanitarian workers were convicted of misdemeanor charges for leaving caches of food and water in the same area. In May 2019, Teresa Todd stopped on the side of a lonely highway in Texas when she was flagged down by three migrants from El Salvador who appeared to be in distress. Border Patrol agents took her into custody, and she remains the target of an investigation that could result in criminal charges. One of the migrants, an 18-year-old girl, was treated for starvation and dehydration and might have died had Todd not stopped.

In ways large and small, the U.S. government collaborated with the American Schindlers in Vietnam intent on doing “the honorable thing.” On our southern border today, in Todd’s words, the government is instead sending “a message to try to chill people from helping others.”

Thurston Clarke is the author of “Honorable Exit: How a Few Brave Americans Risked All to Save Our Vietnamese Allies at the End of the War.”

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinionand Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.