Every kid has a dream growing up; mine was to be an astronaut.

In middle school, I aspired to soar into the stratosphere as a space jockey and had a healthy obsession with all things NASA. I saved money to go to Space Camp, subscribed to Odyssey magazine, and ditched class to watch space shuttle launches on television. (I was so affected by Challenger disintegrating in 1986, I spent hours babbling about the disaster after sustaining a concussion a few months later at age 10.)

Most of all, I idolized the astronauts of the Apollo program, the daring individuals who slipped the surly bonds of earth to become the first humans to set foot on the moon. To this day, I can still name almost every member of each mission.

My hopes of becoming an astronaut may have failed to launch, but my fascination with the space program, and the Apollo program in particular, have remained. It’s gotten bigger lately in the buildup to the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 on Saturday, July 20.

One of the many things I’ve learned about recently in the resurgence of my NASA fandom is how much of a role Arizona played in getting Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and others to the moon and back. Sure, I’d seen the occasional mention in Odyssey about how Apollo astronauts had trained here in the ’60s and ’70s, but never knew the full extent of it until now.

USGS geologist Joe O’Connor in an early Apollo space suit at the Hopi Buttes lava field in northern Arizona in 1966.

USGS

The focus was largely on geology training. After the U.S. beat the Soviet Union in the race to the moon, the Apollo program had more of a scientific focus, particularly Apollo missions 14 through 17. And, for the most part, that involved lunar geology. And thanks to northern Arizona being partially a geologic analog to the moon, NASA sent its rocket men here.

Every astronaut who stepped onto the moon came to Flagstaff, a major point of pride for the town’s scientific institutions that were involved, like Lowell Observatory, the Naval Observatory, and the United States Geological Survey’s Astrogeology Science Center, which even has a display in its lobby touting that fact.

Their scientists may have been just a fraction of the tens of thousands of people who helped the Apollo program succeed, but they were happy to be the shoulders that Armstrong and others stood upon. The experience also helped establish Flagstaff as a science hub.

There are many untold stories about the hidden figures and unsung heroes from northern Arizona who played a role in getting men to the moon.

There’s Patricia Bridges, the illustrator who airbrushed some of the first lunar maps at Lowell; geologists like Joe O’Connor, who redesigned lunar geological equipment on a cocktail napkin at the Hotel Monte Vista; and Gordon Swann, who spent hours wearing early Apollo pressure suits in the hot Arizona sun. A few USGS employees even got to fly a Bell Aerospace rocket backpack in the Hopi Buttes volcanic fields on the Navajo Nation since NASA was considering having astronauts use it on the lunar surface.

I was thrilled to hear about many of these tales about when the astronauts came to Flagstaff, what they did there, and how it changed the town. To learn more, I’ve traveled the state, spoke with an Apollo legend, and walked in the footsteps of my heroes.

This story began with a phone call.

Apollo 13 astronauts Jim Lovell (left) and Fred Haise (right) at the Black Canyon Crater Field, in the Verde Valley in 1970.

USGS

If you’ve seen Apollo 13 as many times as I have, it’s a name you’re familiar with. The film was based upon the unlucky mission of the same name, which was crippled by a mid-flight explosion during its journey in April 1970. Along with crewmates Jim Lovell and Jack Swigert, Haise endured a life-or-death struggle to return to Earth safely.

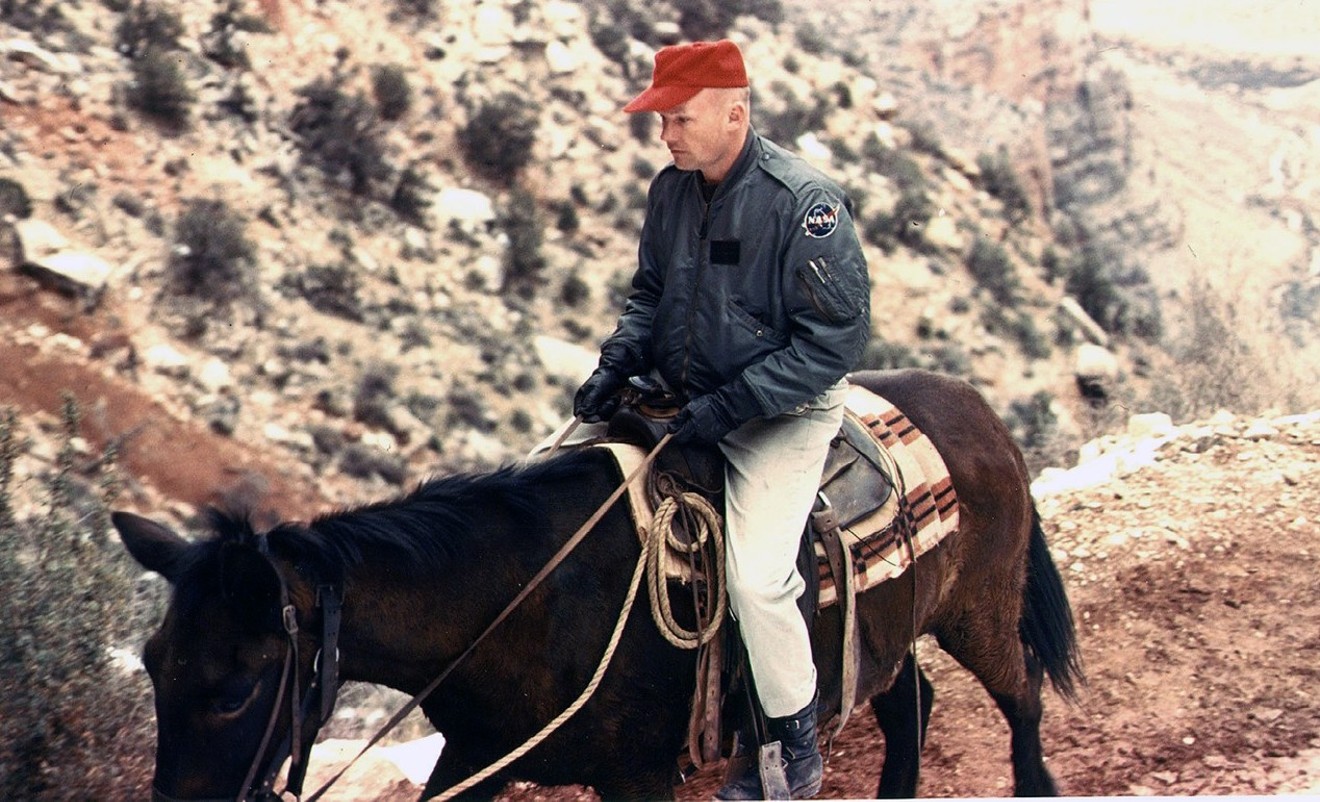

But that was not the topic of our telephone conversation in early July. Instead, it was about his experiences in Arizona. Haise first came here in 1966 with 15 other Apollo astronauts to visit the Grand Canyon for what amounted to Geology 101.

“It was our very first field trip, because the Grand Canyon has a simple set of structures to look at, a nice layer-cake-type set of formations from top to bottom. So we ended up walking all the way down there and coming back up,” says Haise, who was played by the late Bill Paxton in the movie. “I have to say I cheated and rode a burro coming back up.”

Besides getting to skip a long and grueling walk, the experience taught him a lot.

“It was a good picture for someone like myself who had never had any experience reading about geology, or surely learning nothing at school,” Haise says. “I was a complete novice and so it was an enlightening experience.”

NASA had been sending Apollo crew members to the Grand Canyon since the beginning of the program. Starting in 1963, every single astronaut in the Apollo program visited the natural wonder, including Armstrong (who also caught a ride on a burro), Aldrin, and their Apollo 11 crew mate Michael Collins.

Astronauts also spent time peering through telescopes and studying lunar maps at Lowell, which NASA had because it was the only observatory in the U.S. at the time specifically founded for research on the moon and the planets of the solar system. (It’s famously where astronomer Clyde Tombaugh discovered Pluto in 1930.)

Apollo astronauts also visited geologic sites in New Mexico, Oregon, Hawaii, California, Nevada, and even as far away as Iceland. Ryan Anderson, a planetary scientist and developer at the USGS Astrogeology Science Center, says that the Grand Canyon, as well as the Flagstaff area, were even better classrooms for astronauts headed to the moon.

“Northern Arizona is an ideal place for a crash course in geology. It has the Grand Canyon, one of the best-preserved impact craters on the planet, and lots of [old] volcanoes. So if you have a bunch of fighter pilots who need to learn geology really fast, then you’re showing them all these geologic sites,” he says. “It’s a really great way for them to get a feel for the science, walking around, thinking about the rocks, and trying to interpret things in the field.”

Haise and other astronauts also visited nearby locations like Sunset Crater, the Hopi Buttes area on the Navajo Nation, and the Verde Valley, all of which were born from volcanoes, as well as Meteor Crater outside of Winslow.

“There’s no such thing as a perfect analogue to the moon on Earth because they’re very different worlds,” Anderson says. “But the volcanic ash from the Sunset Crater and other eruptions in the area are pretty good analogues for the loose, pulverized rock of the moon. Most of the lunar surface is made of what we call regolith, which is rocks that have been busted up by billions of years of impact, and we can’t have that on Earth. But the cinders from the eruptions that became lava rock are the closest analogue we have.”

Hence the reason why astronauts tromped around former lava fields before heading to the moon. But first, NASA and the USGS had to blow stuff up.

Apollo 16 astronauts Charlie Duke and John Young testing out an early version of the Grover lunar vehicle in northern Arizona in 1970.

USGS

There’s also a tribute to Harrison Schmitt, the geologist turned astronaut who worked at the center prior to walking on the lunar surface during Apollo 17, the final moon mission. Taking up the most space is a massive orange and white geologic rover (dubbed “Grover”) that was used to train astronauts for the final moon missions starting with Apollo 15. The Grover still sports a few dents and paint scratches, as well as a fine coating of black lava rock dust.

There are also photos of enormous explosions that were set off using dynamite and ammonium nitrate in the lava fields around northern Arizona to create craters similar to those on the moon. As you can see in the photos accompanying this article, it was a sight to behold.

The USGS and NASA created several crater fields around northern Arizona, including in the Verde Valley and Sunset Crater. The biggest array was found 15 minutes northeast of Flagstaff in the Cinder Lake field, which boasted hundreds of craters. It was there they field-tested numerous prototypes of space suits, cameras, and rovers over the years.

Apollo 15 astronauts Jim Irwin and Dave Scott driving a Grover (or geologic lunar rover) on the rim of a crater in the Cinder Lake field outside of Flagstaff.

USGS

CBS even sent camera crews to Cinder Lake, as well as the USGS Astrogeology Science Center and other locations in Flagstaff, during its coverage of Apollo 11.

The center owes its existence to Apollo, Anderson says. Famed geologist Eugene Shoemaker helped launch the agency in 1963 after imploring NASA to commit more time and attention into science and not just jingoism.

“He sort of made the connection that, if we’re sending people to the moon we should make sure that we are getting good science out of these risky and expensive missions,” Anderson says. “So he founded our center to provide NASA with the mapping, and the training so the missions were a scientific success as well as a patriotic success.”

“When the moon mapping had been going on for a couple years,” Schindler says. “Shoemaker was one of the scientists who convinced NASA how important it was to the equation.”

Shoemaker, who died in 1997, made sure Lowell was involved in other facets of astronaut science training.

“He arranged it so Lowell was always involved in some way. The astronauts went on field trips to Meteor Crater or to Sunset Crater or the related volcanic fields,” Schindler says. “And then later in the day, they’d go to Lowell to see how these features would be depicted on maps on the moon. The role Shoemaker played was vital.”

Standing in the Cinder Lake fields is like being on another world. I visited there on an afternoon this month and it requires a bit of effort to maneuver through. With every step, your feet sink down several centimeters into the morass of pulverized lava rock with an audible crunching sound. It’s akin to walking through kitty litter.

A black sea of rocks stretches far into the horizon. Buzz Aldrin’s famous line about the lunar surface being “magnificent desolation” rings in my ears. If there’s no breeze, there’s almost complete silence, almost like the total absence of sound that’s found in space or even on the moon.

Although he trained in Flagstaff, the second man on the moon never visited the Cinder Lake crater fields, but many of his fellow astronauts did, including Alan Shepard, Eugene Cernan, David Scott, James Irwin, and Charlie Duke.

A handful of the pulverized lava rock making up the Cinder Lake Crater Field outside of Flagstaff.

Benjamin Leatherman

Countless tracks made by quads and motorcycles criss-cross this ocean of rock, as the area is popular with off-road vehicles. (A second crater field located to the south has been sectioned off with barbed wire fencing in hopes of preserving it for posterity.)

The geologic training conducted by Apollo program still influences the area, albeit over at the USGS Astrogeology Science Center in Flagstaff. Anderson says they’ve been instructing astronauts on the geology of other planets in recent years as NASA is considering new missions to the moon and Mars in the next decade.

“Nowadays we are sort of going back to our roots and we’ve started training NASA’s newest class of astronauts to do geology so that when we do eventually return to the moon or Mars, those astronauts also have a good background,” Anderson says.

And they all aren’t just a bunch of ex-fighter pilots these days.

“Right, yeah. There still tends to be significant amount of military experience but there’s also a lot of scientific expertise,” Anderson says. “And we’re covering basically the same stuff. It’s a combination of sort of classroom lectures and hands-on activities, so if we go back to the moon, we’ll be ready.”

And I hope I’ll be watching when mankind takes yet another step into the great unknown.