Our Apollo-inspired dreams of living on the moon could still come true

As Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin stepped on the moon 50 years ago, we imagined a future lunar life filled with wingsuits and tourist cruisers.

In 1968, Edward Guinan was a young graduate student studying the universe from an observatory in New Zealand. And like countless members of the Apollo generation, he anticipated the moon landing by Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin the following year would be the start of Manifest Destiny, lunar edition.

He believed landing on the moon was just the beginning.

"I was a space advocate, I was involved with building rockets and things of that sort, so I was a big fan of the program," Guinan, who would go on to have a pioneering career in astrophysics and planetary science at Villanova University, tells me.

Some of the observations he made in 1968 from New Zealand would eventually earn him credit for discovering a ring system around Neptune. At the time he looked forward to a coming age of new observatories on the surface of the moon that could see deeper and more clearly into the cosmos, because they would be unobstructed by any kind of weather or atmosphere.

And naturally, doing more science on the moon would require sending more scientists there, something that didn't happen much with the Apollo missions.

"Even though scientists did fly on the last [Apollo mission] they were all test pilots and things like that," Guinan recalled. "They did a good job, but they weren't trained [scientists]."

Wingsuits and dust cruisers

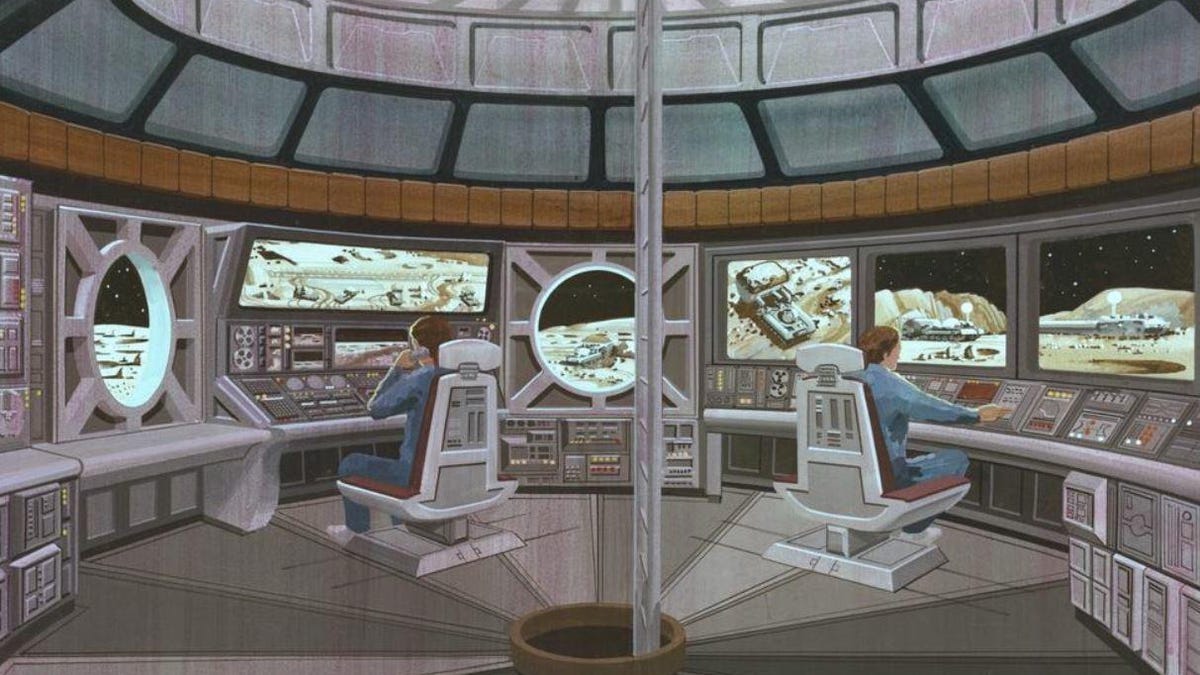

This early concept for a subterranean lunar base comes from the Soviet magazine, Teknika Molodezhi

Guinan was just one of many dreamers at the time who imagined a new role for the moon in the near future.

In 1967, the New York Times Magazine published an essay by famed author and robot evangelist Isaac Asimov alongside a full-page illustration of a concept for a "Lunar City."

"In the next 50 years, by the most optimistic estimate, we can place several thousand people on the moon," Asimov wrote 52 years ago. "The moon colony will be a completely new kind of society ... that might well be infinitely illuminating to the billions who will watch the process from Earth."

The illustrated moon metropolis included a nuclear power station, mines, moving sidewalks, farm domes, housing, a university and art gallery and, of course, people flying around in low-gravity wingsuits.

For years leading up to Apollo 11, similar images filled screens and pages worldwide. The habitats for lunar living and working were often a combination of domes and underground dwellings. Using ancient lava tubes or other holes in the moon's regolith, the idea was to shield the new moonies from all that nasty stellar radiation that Earth's atmosphere normally protects us from.

"I believe we, at a minimum, envisioned setting up lunar colonies and shuttling people there -- not just scientists and pilots but also tourists and families," says Ella Atkins, a University of Michigan aerospace engineering professor and IEEE senior member.

This 1965 Soviet film titled simply Moon is filled with plenty of space race propaganda, but ends with a vision of the first lunar family, who presumably speak Russian:

The moon was also a popular setting for all sorts of popular fiction in the mid-20th century. Science fiction writer Robert Heinlein spun a tale of revolting lunar colonists in his 1966 novel The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, and the legendary Arthur C. Clarke also attempted to tell realistic stories of settling down on our natural satellite.

Before the Apollo 11 landing in 1969, there was significant uncertainty over just what the consistency of the moon's surface might be, with some believing that it might be covered by a layer of fine dust that flows almost like water. If such a layer were deep enough, it could present a serious pitfall for lunar explorers almost like quicksand on Earth.

Clarke's 1961 novel A Fall of Moondust tells the story of hydrofoil-like vehicles that cruise over seas of lunar dust and the moonquake that leads one such cruiser full of tourists to become trapped beneath the surface of the dust.

In a scene from 2001: A Space Odyssey, an astronaut makes contact with an alien monolith on the moon.

But the author's influence on how humans would envision our seemingly inevitable march deeper into space would peak the year before Apollo 11. That's when Clarke and director Stanley Kubrick collaborated on the classic 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey, based on Clarke's 1948 story, The Sentinel.

While much of the film's action centers on a spacecraft in deep space near Jupiter, a key scene involves an odd alien monolith found on the surface of the moon.

David Bowie was inspired by the Kubrick film and released the song Space Oddity the same month as the Apollo 11 moon landing. Poetically, the song was later covered by Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield while floating above Earth aboard the International Space Station, becoming a viral sensation.

Of course, it wasn't just futurists and fiction writers conceiving of how we'd live and work on the moon during the Apollo era. NASA had multiple plans on the drawing board in the 1960s for hardware to build a lunar base: the Apollo Extension System and the Lunar Exploration System for Apollo. It also turns out the US military was working on its own concept to operate on the moon even before Apollo 11. Project Horizon was only declassified five years ago.

None of these initiatives ever got off the ground, however, and as we know, the era of humans on the moon ended with the Apollo program in 1972.

From Apollo to automation

But Edward Guinan got a shot at making his Apollo-era visions of moon-based astronomy a reality when he became involved with a new effort to go back to the moon. NASA's "Moon Base" initiative began in the 1980s and looked at building a permanent presence on the moon that could potentially include an observatory.

Illustration of a lunar base concept from 1989.

"It was to use the moon as a platform for putting large telescopes up," he explains. "And putting a big radio telescope on the far side of the moon so it wouldn't get interfered with by radio transmissions from us."

A number of studies in the 1980s and 1990s proposed a lunar base that could be operational by the 2010s, but they never made it off the printed page. Guinan says NASA's focus at the time was the space shuttle and no funds were ever allocated for a Moon Base.

Harvard astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell tells me that Apollo-era visions of bases on the moon or Mars became less attractive over time, especially as automation advanced more than perhaps many people foresaw in the 1960s.

"I don't think we anticipated the number and variety of robotic satellites and their level of integration into everyday life: Especially the implications of ubiquitous GPS."

Guinan has worked from telescopes in Iran and New Zealand, but not the moon, yet.

IEEE's Atkins adds that while we have exponentially more computing power now than NASA had 50 years ago, "rocket propulsion has not undergone a revolutionary change, at least to date. Therefore, we likely would still require very long trips to shuttle people and supplies to/from the moon, and each trip would be costly in dollars and to the environment."

Atkins sees a role for today's advanced tech off-Earth that could finally make those Apollo era visions of lunar life practical enough to become a reality.

"As AI and robotics technologies grow, we now envision that future human habitats will be occupied by a range of robotic collaborators and companions that will help make sure human explorers have time to explore rather than mostly maintaining life-sustaining equipment and themselves (e.g., with extensive exercise each day)."

The technology of the 21st century and NASA's new push to return to the moon by 2024 "to stay" could mean that Edward Guinan might finally see more science happening on the moon after decades of stasis.

As for the low-gravity wingsuits and family cruises across seas of lunar dust, we may need to wait another 50 years.