There’s an air of romance to nearly all the places Shiromi Pinto describes in Plastic Emotions, her novel about a love affair between two great 20th-century architects. Some of those places are tropical and alluring. In Sri Lanka, we head to Kandy with its verdant hills, and then Colombo with its chattering bourgeoisie. In India, Pinto takes us to Chandigarh and its elegantly experimental modernist buildings. Even in Paris and London, we are surrounded by the glamour of bohemians and their postwar parties. But it’s in the mildly prosaic confines of a conference in Bridgwater, Somerset, that the Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier seems first to have collided with a Sri Lankan architect called Minnette de Silva.

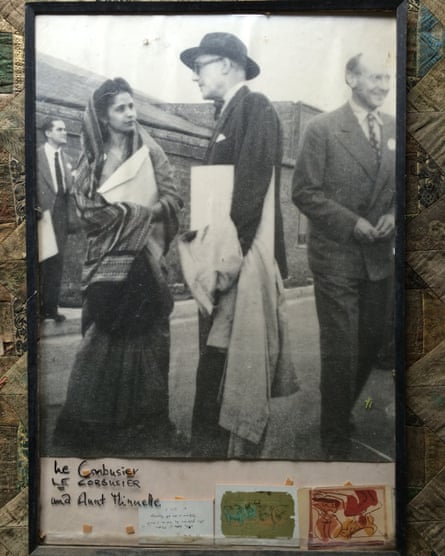

It’s there that the illustrious Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne descended in 1947 for a conference. The delegates included the modernist architects Walter Gropius and Ernö Goldfinger. A photograph of the attendees shows Le Corbusier bespectacled and bow-tied at one end of the front row, and the young, bird-like De Silva in a sari, seated further along. If they seem an unlikely couple, a more candid photo seems to capture something of their mutual interest. They are mid-conversation: he is talking, smart hat perched on his head, a coat casually slung on his arm, while she clutches papers close to her chest, the tail of her sari wound over her hair in the traditional way. She gazes at him intently.

Looking at the photograph, it seems unsurprising that this real-life encounter and the exchange of letters that followed should have provided Pinto with the bones of her story. Plastic Emotions is an exercise in romantic speculation. Pinto imagines the nature of the relationship that develops between the 29-year‑old Sri Lankan and the ageing pioneer of urban modernism. She gives them trysts, meaningful exchanges, a separation and then painful longing, ending only with Le Corbusier’s death in 1965.

Pinto luxuriates in their imagined love affair, revelling in the anguish of their estrangement. It’s hard not to be swept away by it all, although she never makes clear exactly how closely she cleaves to real life. Le Corbusier was married but not always faithful, and De Silva’s letters certainly indicate an intense attachment to the man she considered her mentor. And yet, what matters in the end is not the realism of the romance but the life that Pinto describes through this device.

Born in 1918, Minnette de Silva was the daughter of a reformist politician and a suffragette. She was Sri Lanka’s first modernist architect and the first Asian woman to become an associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects. She trained in Bombay, then London, where she cut a striking figure in architectural and artistic circles, encountering Pablo Picasso and Laurence Olivier, among others. In letters she exchanged with Le Corbusier, he addresses her affectionately as “oiseau”. She calls him “Corbu”. He signs off with a sketch of a crow.

But by 1948, with the dawn of Sri Lankan independence, De Silva had left Europe to return home, setting up a studio on the family estate in the Kandy foothills and lending her talents to high-end domestic commissions and social housing projects. It’s here that Pinto bestows on her heroine the fervour of a modernist visionary, conveying how urgently De Silva understood the functional urbanism that a new Sri Lanka would need, how quickly it must be built and how beautiful it might be. Pinto is at her best when she takes us beyond the romantic agony into the design aesthetics. She shows us De Silva’s sense of invention, her determination to meld modernist architecture with traditional craftsmanship, her insistence that a built structure should have some relation to the rocky landscape into which it would be cut. In this way, the novel seeks to give voice to De Silva’s distinctive architectural vision, countering Le Corbusier’s propensity for grand pronouncements on urban planning and the “poetry of the right angle”.

The book is most valuable for its portrait of De Silva – a woman so unquestionably intelligent and intriguing that it feels scandalous she should be so little known. Pinto’s prose is a little too prone to starry skies and roses in the hair, with a preponderance of exotic tropes and a sometimes sickly lyricism (“the moon is a silver lozenge on an inky tongue”). But the novel makes clear how the idea of male genius can blot out other kinds of history and legacy. It will make you want to seek out De Silva’s work and remember her name.