A lead role with the Royal Shakespeare Company is a dream gig for an actor at any point in their career. In 2006, straight out of drama school, I had it in my grasp. I’d already signed with one of the most powerful agents in the business, who operated out of a gymnasium-sized office fringed with hanging plants and succulents. I’d pop in every now and then just to steal the toilet paper, which was enriched with natural butters. We’d have meetings, the only purpose of which were to tell me how great I was and discuss what I wanted to do. I’d take my shoes off and put my feet up, wanting to be at home in the feeling.

The audition was for a uniquely brilliant new play called The Indian Boy, a modern retelling of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, focused on the changeling who is fought over by the king and queen of the fairies. The play placed this feral child, literally raised by animals, in a psychiatric unit as doctors try to socialise him. Rona Munro’s script was a wonderful, layered exploration of what it means to be human, and from the title page I visualised it as a giant finger crooked from the heavens, ready to hoist me skyward. I am a changeling boy, I thought.

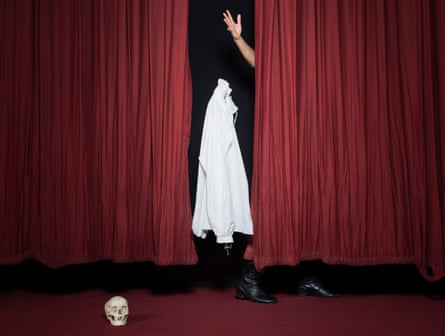

A few minutes into the audition, I knew I would succeed. The lack of confidence I felt elsewhere in my life melted away, as I swapped out my central nervous system for The Indian Boy’s, and looked through his eyes. It helped that the character was displaced, mistrustful and mostly mute. The back of the set was a monumental cage wall, on which I clambered and perched and slithered on all fours like a gecko, more at home than I was on the ground. Prowling, the stamp of hooves, tilt of a curious bird’s neck: I understood all these things, and howling, too. “I had to force myself to watch the other actors occasionally,” the director later admitted, following the group workshop that landed me the part.

The reviews were uniformly ecstatic. The show sold out. A magnetic field, the one that surrounds anyone in control of their career, thrummed around me. It was the Samadder CV at the top of the pile; I was being invited to the advent-calendar version of life, with a chocolate behind every door. My agent lined up meetings with influential casting directors and producers. The future yawned and touched the horizon, and for the first time looked inviting. Acting is easy, I thought.

The Indian Boy played in November, at Stratford-upon-Avon, Shakespeare’s home town. By December, we were done, and we weren’t the only ones. My father, who was in his 70s but active, was admitted to hospital. He came home for Christmas and my birthday, but checked back in come New Year. Days later, a nurse called. He’d lost his speech and I should come in. He died that afternoon in front of me, and the blast took me out.

Actors occupy a tragic place within the arts, in that they cannot practise their craft alone. They cannot sing to themselves or retreat to a rose garden with a canvas. There is no joy to be had in practising monologues. They need other actors and an audience. They exist in the minds of others or not at all. After my brief moment of glory, I began exploring the second option: flat on my back and not getting up for anybody.

It is said that in a major city you’re never more than six feet away from an actor; if you listen closely, you can hear the scuffle of their claws against the skirting. Every day they’re hustling, hustling. I was doing nothing, writing to nobody, not picking up the phone. After a year of rumours that The Indian Boy might transfer to London, I accepted that it wouldn’t. It was too difficult to move the cage, apparently.

It didn’t help that I hated every other job I was sent up for, the majority of which were terrorist dramas. They differed only superficially. All had been plucked from the same script tombola, stuffed with tickets reading sister, honour, paradise, cell, vest, mosque, mobile, detonate. Of all the motives that teem within the human heart, revenge against the kuffar was low on my list. The fixation with intercepted text messages and glass-walled rooms bored me, the kind of boredom that is actually anger in costume. I was furious at the double standard and people telling me it was a good time to be an Asian actor.

It was hard to explain without sounding ungrateful. What would it be like if, every time a white English actor received a script, it always concerned the 1846 repeal of the Corn Laws? You’ll be playing an extremist farmer, hellbent on reviving the Napoleonic wars in order to push up wheat prices. Every single one. You’d understand if their habitual response was, “This again?”

“There’s enough room for everyone at the table!” people told me, which was objectively false. There were four good parts a year written for Asians, and three of them involved knowing the Urdu for “bridge” and “midnight”. I got down to the last two for a lot of jobs, but I’m not convinced this isn’t something agents tell all their clients, to keep up morale. You’d have a fantastic meeting about a fantastic project, hear nothing until eight months later, when you’d see it on TV with another actor in the lead.

Strategically, I decided to play possum: I would abandon hope for a while, stop trying, but only until Riz Ahmed was too famous to be going up for the same parts as me, at which point I’d swing back into the game. Which I did, only to start losing them to Dev Patel. My agent dropped me and removed my photo from the website. This didn’t hurt my pride, as I had none left.

I started to grow bitter, believing myself more talented than my peers, as the supporting evidence grew more scarce. I started looking out for interviews with Danny Boyle. He would always repeat the same anecdote about Slumdog Millionaire, which I’d gone up for. About how it had been impossible to find any Asian actors who weren’t Bollywood beefcake types, until his daughter recommended a skinny unknown from her favourite teen drama. “WHY ARE YOU LYING, DANNY BOYLE?” I would shout in the newsagent’s, reading a paper in which I was erased from the narrative. Stupid Dev Patel. Why was he given so many chances?

And me? I was the face of Arla Dairy milk, for a time, at least in the Bangladesh territory. At least, I think I was. I never actually saw that advert. A friend texted me once to say it was airing on the Asian network, when they were at their parents’ house. Unless that was Tolly Boy Rice, who hired me to play a father of four. The casting prompted a little existential crisis once I realised that, now I was in my 30s, it wasn’t unreasonable.

I moved back in with my mother, for a much-needed pit stop of 14 months, in which I took the opportunity to “recharge my battery” (translation: have a breakdown; punch bread in supermarkets). Despondency mouldered to resentment and desperation. I registered with every casting website going, checking every box in the skills section: unicycle, rat-trapping, playing the spoons. I was skydive-certified and spoke Swahili. I’d take any audition – just get me in the door.

Having transferred to a more boutique agency, I told them I didn’t want to go up for any more shows with bombs in them. They did their best, and I landed parts as a pick-up artist in Doctors, a smooth suitor in Emmerdale, a doctor in Coronation Street. I took a picture of myself on set outside the Rovers Return. They serve real beer there, which apparently tastes better than any in the country, because they clean the taps once a week. But none of it was enough to survive on, and the fact that I was temperamentally unsuited to any of this was becoming harder to ignore.

For many, following the career path of an actor means temping on reception desks, working unpaid evenings and weekends in fringe shows for the exposure. It means never allowing yourself a holiday, on the off-chance your agent calls because there is a schools tour of Treasure Island workshopping at short notice and apparently you play the Northumbrian smallpipe, or so it says on Spotlight. Hitting rock bottom can have a certain nobility, but my lowest points in acting were so absurd I was denied even this. That’s what struck me as I stood in a cluttered space in north London that was apparently functioning as a theatre.

“Coo-ee!” a voice assailed me as I walked downstairs into a damp, low-ceilinged basement. A bulbous woman with a sprig of spiked hair was tipping towards me. “I’m Andrea,” she said in a breathless Canadian accent. “Won’t you come on in?” There was no way to come in any more than I was, the basement being an undivided floor akin to a deserted car park. Andrea ushered me towards a school table, introducing a woman with her hair pulled into a tight bun. “Christine is my other hand.”

“Let’s hear your piece,” said Christine, who clearly had a policy about small talk. I was anxious to make a good impression. I can’t remember if this audition had come about via my trawler net of lies or a chain of tip-offs from friends unable to take the job themselves, but it certainly didn’t feel like a sure thing. They never did any more.

It’s hard not to be your own worst enemy in this business. Having landed a single line in a film, you stay up at night wondering how to deliver it with such magnetism that any producers watching will be whiplashed by the raw charisma of Man with Cup. You’re in a similar bind when choosing audition speeches: torn between playing safe and meeting the director’s expectations, or revolutionising the form. That’s why I was second-guessing myself, standing in a basement, limbering up an interpretive-gesture adaptation of Walt Whitman’s Scented Herbage Of My Breast. It had felt right when I did it in my bedroom, but that shouldn’t be anyone’s guiding philosophy.

“Leaves from you I yield, I write, to be perused best afterwards,” I warbled, a sweep of the arms inviting my audience to consider their relationship to time. In this I was successful, as it became apparent they were in a rush.

“That’s just great,” Andrea decided in the first brief pause. “We’ve only got 20 minutes, so shall we dive in with the puppets?” Apparently, I’d missed a meeting.

“I don’t remember any mention of puppets. I’m certain I would have remembered that.”

“Yah! A mix of musical and puppetry, full-body to sock. Shall we dive in?”

“We’re 40% there with the funding, but we’re booking the tour now to keep momentum going,” Christine added, seeing that I was lost. “Six venues in the west of Scotland, driving back to Cumbernauld each night. Could be a tough crowd, so the politics won’t be overt, but the aim is to push buttons. How do you feel about puppet nudity?” It was not something I’d considered.

“It’s not something I’ve considered.”

“Great! Let’s get you a partner. Would you like to choose?” offered Andrea, introducing a mound of oversized grotesques.

I thrust my hand into the clump. There was a Playboy bunny, a radish with a mouth but no eyes, one that looked like Hitler. Gazing up at me from the floor, with its squashed approximation of a face, was a cock made of felt. This was a minefield. Wondering how to avoid the contempt payments that would surely be sought by the Whitman estate if they got wind of this, I settled on a monumental sea clam. Its umber body was corrugated with dun fur, parted by wavy lips and a vivid red interior.

“A man who’s up for a challenge. We like!” burbled Andrea. “Let’s hear your piece again, this time from Esmeralda.”

I turned Esmeralda over, finding an operational cleft on her base, marked by an elasticated collar. I don’t know if you’ve ever attempted, under pressure, to ventriloquise a clam the size of your head in front of strangers in the service of an unorthodox reading of Leaves Of Grass, but it isn’t easy.

“Really try to punch the comedy,” advised Christine, unhelpfully.

The hard part wasn’t locating bankable gags in Whitman’s transcendental elegy. It was moving the clam’s mouth. The lips were spongy, neither fully closed nor open. I rubbed my thumb and fingers, like a cartoon gangster demanding payment. I quacked my hand, turned it sideways. The overall effect was of something unspeakable struggling to be born.

“Death is beautiful from you,” I started. Esmeralda gurned and mashed her gums. “What indeed is finally beautiful except Death and Love?”

“Comedy!” reminded Christine. I spun the mental Rolodex, imagining how a sea clam would talk. All I could think of was Davy Crockett but I had no idea what he sounded like, or even who he was. A pirate?

“Arrrrr, how solemn it grows, to ascend to the atmosphere of lubbers,” I growled, sounding like an Irish alcoholic. At least Andrea was smiling.

“Punch the double entendres, anywhere you can,” Christine commanded. Was this really what I was doing with my life?

“I am determin’d to unbaaare this breast of mine.” I winked, accent slipping, as if we were now auditioning Carry On Up The West Country. “Let Esme! Let Esme!” yelped Andrea, gesturing to Esmeralda.

“You’re not funny – she’s funny,” reminded Christine.

“Do not fold yourself so in your pink-tinged roots!”

What was this, Larry Grayson at the hairdresser’s? How long would they let this go on? “Oh, burning and throbbing,” I groaned. “I will raise immortal reverberations…”

“That’s so great,” cooed Andrea kindly. “The Lady Garden is tricky to get the hang of.”

Lady Garden? My brain felt like stretched-out putty. I saw, so obvious and yet too late, that I had my hand inside an anatomically exaggerated vagina.

Falling out of love with acting was a slow process of estrangement. Difficult to know when to leave, but fairly straightforward to know that I should. It boiled down to one question: how does this make me feel, most of the time? The limitations of this career, which I once found charming beyond reason, now struck me as simply unreasonable. My thoughts grew painfully widescreen: I couldn’t live my life like this. When an actor has this realisation, there is no other option: she will spend at least another seven years struggling by, because doing what is best is agonising.

A performer never stops wanting to perform – the connection, elevation of the moment and search for emotional truth make them feel alive like nothing else. This is a dangerous predicament in a career where 90% of the workforce is out of a job, feeling unconnected, un-alive. I loved acting, but it didn’t look after me. It broke my heart a different way every month. How would it feel to let a vocation fall away? It was impossible to imagine.

“Got a meeting, vee hush hush. Can’t say what it is!” my agent whispered, which was a problem, as that was literally her job. “All right – it’s Take That!”

“What is it?”

“They were a boyband in the 90s. Gary Barlow…”

“No, I know who they are. What’s it to me?”

“They’re looking for dancers, but you don’t need to be able to dance.” This was the sort of cryptic briefing I’d get a lot. They’re looking for singers, but not singers. They want someone beautiful, but not so you’d notice.

For fuck’s sake, I thought, striding along the upper floor of a dance academy. The long, panelled corridors streamed with seven-year-old girls in pink satin. I found the room. It was palatial, with a small group standing against the mirror on the far wall, very far away, like Live Aid. Casting directors make up their mind within three seconds of you walking in the door, we’d always been told. There may be more disempowering workplace truisms, but that one was definitely down there. In theory, I could have lost the job seven times before I made it over to them.

When I eventually arrived, I was instructed to sit in the lotus position on the floor and mime playing sitar to a Beatles track. Ahhh. So that’s why I was here. To add Indian flavour to a number on tour. They were going to have dancers emerging from an elephant and, I don’t know, throwing mango chutney around.

When the track started, I plucked abjectly at an imaginary sitar and wondered whether all the wrong turns I’d made in life would be enough to fill a quarry, and how big a quarry was. “Wait until the sitar part starts,” one of the men instructed, with slight impatience.

“But I’m not actually playing anything,” I said. For some reason, I was also not playing it quite badly. To prove I knew that sitars were very big I was miming something the length of a grandfather clock, which I couldn’t control. Splayed fingers struggling to reach strings, me toppling under the weight. The men were looking at me in great confusion. They didn’t ask why, when asked to imagine an instrument, I imagined one I couldn’t play. I didn’t explain that I was very, very bored.

“You’re welcome,” I said, before they had thanked me for my time.

My agent rang a few days later. Actually, her assistant rang, asking if I could print more colour headshots and send them over. I told her I was quitting acting. I was scared of my agent and thought the news would be best if it didn’t come from me. I could hear the colour draining at the other end of the line, and sometimes picture the follow-up conversation. “Did he say when to expect the pictures?” “No, he said he was leaving and never to call him again.” It wasn’t the bravest way out, but I’d never been good at goodbyes.

Shocking, how the things we want can change so drastically over time. By 2015, I’d fallen into another ridiculous career: reviewing kitchen gadgets for the Guardian, having accidentally become a journalist or something adjacent to it. One night I was invited to cover the Baftas, the glitziest awards I’d ever been to, the glitziest anything, really. The invitation filled me with stress. “What does ‘black tie’ actually mean?” I wondered.

I image-searched “Bafta” and it threw up a picture of Eddie Redmayne dressed as Rupert the Bear, which didn’t help. A workable definition of fame is a group of people who don’t carry their own bags, so would there even be a cloakroom? And how would I get to the Royal Albert Hall? “Practice,” an unhelpful friend advised.

Arriving at the Baftas on my own was like going to any party where you don’t know anyone, except that everyone there was the most elegant person I’d ever seen in my sordid life. I felt like David Attenborough examining a rare colony, populated exclusively by birds of paradise and emperor penguins. There was no cloakroom.

But quite a long way into the show, there was someone who looked like me: Dev Patel, winning an award for his beautiful work on the film Lion. I watched as he thanked his people, who had worked tirelessly to help “a noodle with wonky teeth and a lazy eye trying to get work in this really hard industry. I’m overwhelmed,” he stuttered. “I’m terrible at this and it means so much.”

I found myself feeling happy for him, this talented man who had come from little and risen so high.

After an astonishing dinner, the ballroom at the Grosvenor House Hotel opened for the after-party. I pushed in line to be served a cocktail inside a real pitcher plant plucked from a vine, smoking at its brim. I felt like Alice in Wonderland, drunk on the occasion. With help from a far more connected journalist, I scored an invitation to Harvey Weinstein’s party at the Rosewood Hotel, which might as well have been Mount Olympus. Finally, I had gained entrance to the innermost circle. The curtains would be parted. I might even meet the wizard.

Inside were mirrors and marble surfaces, darkness. A room at the back was made up as a French patisserie, with macarons, millefeuilles and opera cakes stacked on shelves for the taking. The chocolate fountains came in milk or white, possibly in response to calls for greater diversity at awards shows. The concentration of stars was ludicrous. I pushed past Casey Affleck, JK Rowling, Riz Ahmed, apparently still working. Yet, absurdly, there was a smaller VIP section in the middle of the room, with the artists and all the famous people I recognised outside it. As far as I could make out, Weinstein was one of about five people inside, and no one was smiling. What was the need for another velvet rope?

I stayed too late, but I’m not sorry about that. As the night was winding down I found Dev Patel, standing at the bottom of the stairs, still looking overwhelmed. I told him it was nice to see a fellow brown man up on that stage, holding his own. It was a relief to realise I meant it. “Thanks, brother,” he replied, smiling.

This is an edited extract from I Never Said I Loved You by Rhik Samadder, published by Headline at £14.99. To order a copy for £13.19, go to guardianbookshop.com.

If you would like a comment on this piece to be considered for inclusion on Weekend magazine’s letters page in print, please email weekend@theguardian.com, including your name and address (not for publication).

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion