- India

- International

The times that shaped Mirza Ghalib and his immortal poetry

Even 150 years after his death, Mirza Ghalib remains one of the most quoted — or misquoted — poets in India. A look at the enduring relevance of his work.

Poets of the fall: Mirza Ghalib. (Illustration: Suvajit Dey)

Poets of the fall: Mirza Ghalib. (Illustration: Suvajit Dey)

Rakhiyo Ghalib mujhe iss talkh-nawai main maaf

Aaj kuchh dard mere dil mein siwa hota hai

(If Ghalib sings in a bitter strain, forgive him

Today pain stabs more keenly at his heart)

Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib (1797-1869), the pre-eminent poet of Delhi, lived through one of the most turbulent periods of recent Indian history and was a witness to the evanescent Mughal rule. Two worlds — the decaying and the emergent — were fusing and merging virtually before his eyes. Pathos, confusion and conflict reigned supreme as the Great Revolt of 1857 marked the end of an era and a new world order lay waiting to unfurl.

Living in Delhi, Ghalib saw madness and mayhem descend upon the streets of his beloved city and witnessed the siege and slaughter of an entire way of life. While, to some extent, his response to the events of 1857 are contradictory, since he was dependent on the pension he received from the British (he was, in his own words, a namak-khwar-e-sarkar-e-angrez or an “eater of the salt of the British government” on account of his pension), there is much in his oeuvre that is a testimony to his times.

There are, for example, the three couplets Ghalib wrote in 1862, possibly in response to the Nawab of Farrukhabad being picked up by the British for aiding the rebels, and abandoned on an island off the shore of Arabia. These verses reflect the hopelessness and escapism that afflicted many Muslims of his generation; they reflect the despair many experience today as the world one knew is slipping away before one’s very eyes:

Rahiye ab aisi jagah chal kar jahan koi na ho

Hum-sukhan koi na ho aur hum-zaban

koi na ho

Be-dar-o-diwar sa ik ghar banaya chahiye

Koi hum-saya na ho aur pasban koi na ho

Padhiye gar bimar to koi na ho timardar

Aur agar mar jaiye to nauha-khwaan koi na ho

(Let us go and live somewhere where there is no one

No one who speaks to me in my language, no one to talk to

I will make something that is like a house

(But) There won’t be any neighbours, nor anyone to guard it

Were I to fall ill, there will be no one to tend me

And when I die, no one to mourn me)

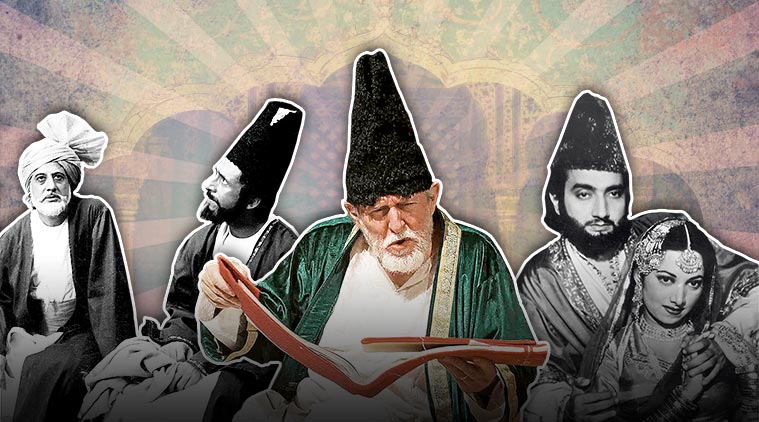

From Bharat Bhushan to Naseeruddin Shah to Tom Alter, Ghalib has been played by doyens of popular culture.

From Bharat Bhushan to Naseeruddin Shah to Tom Alter, Ghalib has been played by doyens of popular culture.

Ghalib did not live long enough to see the coming together of the writer and social reformer or the increasing social consciousness evident in Urdu literature nor indulge in any experiments with “colonial modernity” as his immediate successors, such as Altaf Hussain Hali (1837-1914) or Muhammad Husain Azad (1830-1910), could. He enjoyed a long innings as a poet (having begun his poetic career as a lad of 11 in Agra before moving to Delhi), was a versatile writer (apart from writing the ghazal, masnawi and qasida in both Urdu and Persian, he was also a prolific and passionate letter writer), met many different kinds of people (from royal patrons to ordinary people in the bazaars not to mention the many firangis to be found in Delhi) and, in an age when travel was rare, he journeyed to Calcutta. The sheer range of his experiences possibly made him the man he was — liberal, humane, witty, proud, touchy and sociable.

Ghalib found friends in almost all the cities he stopped in along the way. He was new to the places but never a stranger. This is proof not only of his stature and popularity as a poet but of the existence of an informal network of contacts — in spite of the long distances and poor communication systems. Being a part of the feudal elite, Ghalib took any help that came his way as his due and was never lacking in assurance and optimism. He also displayed every trait of a born traveller: he enjoyed the new and the different yet could distinguish between high and low, and had clear likes and dislikes.

The late 1820s were witness to the changing ground realities as well as the altered relationship between the British and the feudal nobility. Ghalib found himself in the crosshairs of a paradigm shift when he set out on his long voyage in search of — what he considered — his rightful legacy in November 1825 and returned home four years later. He wasn’t successful in his objective but he returned no doubt a wiser man, one who had seen the world and its ways — having travelled, variously, by horse, cart and boat. Ghalib returned to Delhi, angry, dejected and deeply bitter towards the British. Yet, despite his disappointment, he continued a ceaseless barrage of correspondence and never quite gave up the hope that one day his pension would be enhanced. Despite his tenacity, Ghalib could never get a paisa more than the original amount.

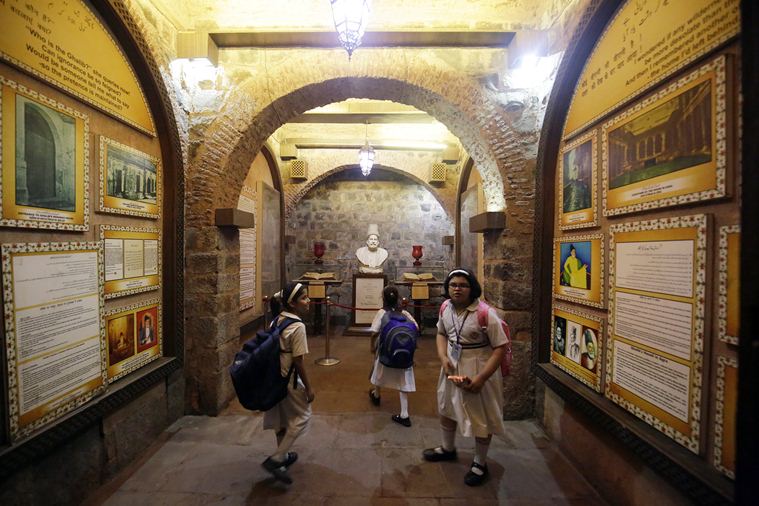

The poet’s world: Children at Ghalib ki Haveli in Chandni Chowk, Old Delhi. (Express photo by Praveen Khanna)

The poet’s world: Children at Ghalib ki Haveli in Chandni Chowk, Old Delhi. (Express photo by Praveen Khanna)

Ghalib’s share of a hereditary pension was Rs 62 and 50 paise per month. While adequate for a modest lifestyle, it was never enough for his expenses: French wines, gambling, and his mistress. Money, or rather not having enough of it to spend, remained a lifelong preoccupation. He was forever borrowing and never in a position to repay. By 1826, his financial affairs had become critical as his creditors were losing patience, his debts were mounting and he had no way of returning even the interest, forget the principal amounts he had borrowed from the city’s major money-lenders — Mathura Das, Darbari Mal and Khub Chand — not to mention various small-time shopkeepers, grocers and family members. Ghalib undertook the long journey to Calcutta as much to escape the clamour of the creditors as to find a solution to a chronic problem.

Ghalib pressed his case with the British authorities at every level: from the Resident at Delhi, the Lt-Governor at Agra, the Governor General in Council at Calcutta, the Court of Directors of the East India Company in London and, finally, Queen Victoria herself. It was not as though he was short of patrons or did not know enough people of high rank from among the new elites of the British in India.

Simon Fraser and Andrew Sterling — both Persian scholars and high officials — wrote letters of recommendation, as did George Swinton, chief secretary to the government. Despite these connections, Ghalib got no reprieve because in the changing political climate, a new indifference had set in to the demands of the old feudal elite. When the case was taken up for hearing, the judgment went against Ghalib — not because his opponent was better connected or had a stronger case, but simply because people like Ghalib had little political currency now. The new British attitude in the immediate aftermath of the Revolt was to deal firmly with what was perceived as a “parasite class”. Ghalib and his ilk — with their pretensions of social/cultural superiority — were given short shrift.

In the aftermath of the Revolt, Ghalib had written:

Likhte rahey junoon kee hikaayat-e-khoon chakaan

Harchand iss main haath hamaare qalam huvey

(We kept writing the blood drenched narratives of that madness

Although our hands were chopped off in the process.)

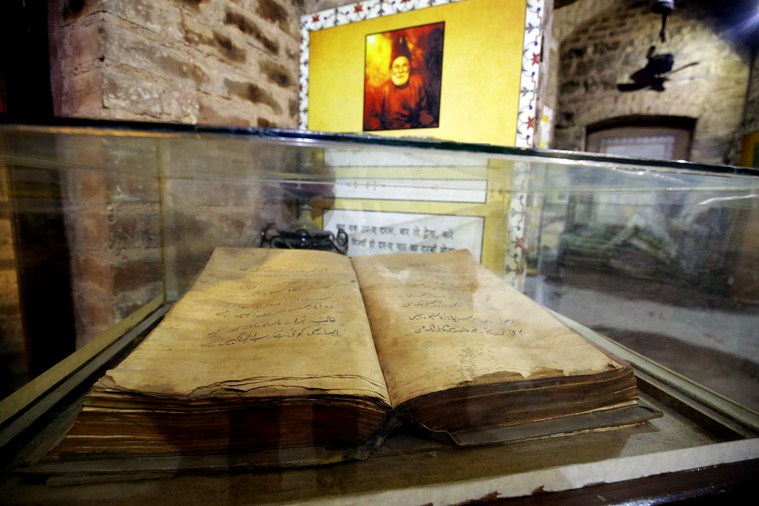

Exhibits at a museum in the heritage structure. (Express photo by Praveen Khanna)

Exhibits at a museum in the heritage structure. (Express photo by Praveen Khanna)

Ghalib’s hands were not chopped off. He lived another 12 years after the Revolt and witnessed the confusion and disarray that followed the loss of power and patronage. His pension was eventually restored in 1860. I suspect it had less to do with Ghalib’s tenacity and more to do with the conciliatory spirit of the British who could afford to show magnanimity to loyal subjects such as Ghalib.

Or, perhaps, it had something to do with the intercession of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan and the Nawab of Rampur who had, to use a modern term, greater “traction” and were, therefore, better suited to negotiate a colonised world.

Rakhshanda Jalil is a Delhi-based writer and translator. This article appeared in the print edition with the headline ‘Lines for Long Journey’.

Apr 18: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05