The Iconic Murals Of Millard Sheets Are Disappearing From LA

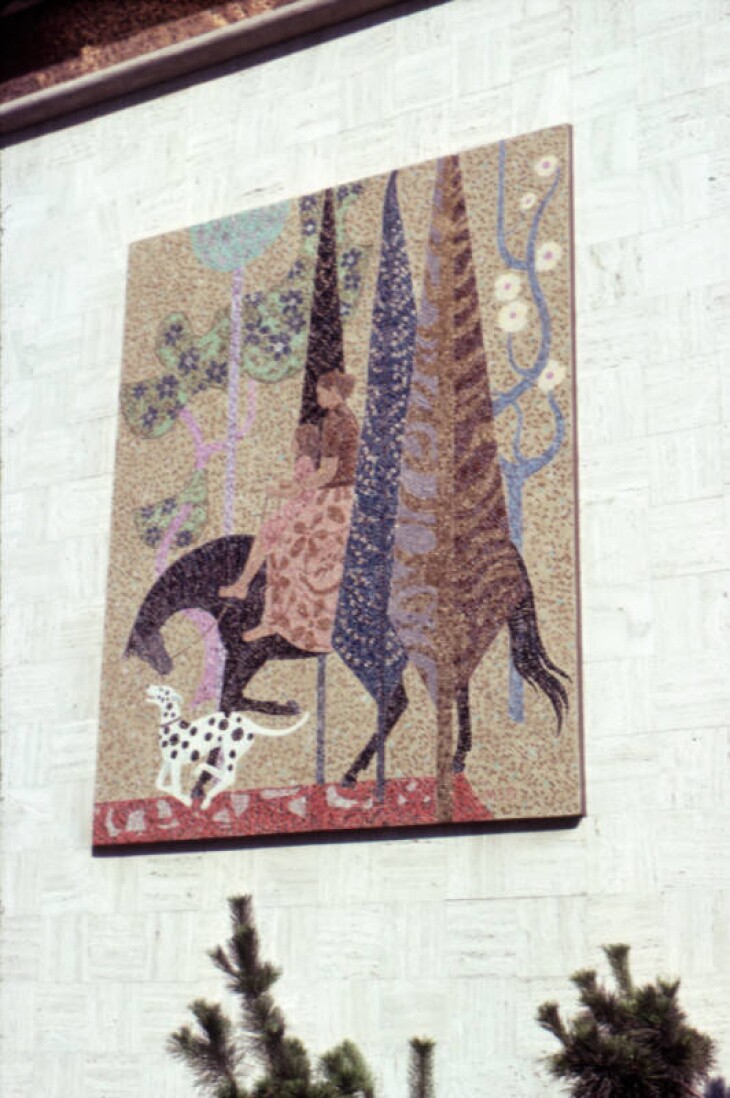

On June 17, scaffolding went up at 2600 Wilshire Blvd. in Santa Monica. Workers hadn't arrived to start building something new. They were there to begin the meticulous process of removing "Pleasures Along the Beach," a gorgeous mural that has adorned the the Home Savings Building since its construction in 1970. Depicting the history of Santa Monica's seaside pleasures, the 16.5-foot by 40-foot glass mosaic was assembled by artist Nancy Colbath on behalf of the Sheets Design Studio. Both the mural and the building were designed by Millard Sheets, an artist and architectural designer who created some of California's most recognizable public art fixtures.

His works — epic, robust, hopeful, implacably American and geared toward the public good — include the Scottish Rite Masonic Temple (now Marciano Art Foundation) on the border of Hancock Park and Koreatown as well as the "Angel's Flight" painting at LACMA. He also designed the Raymond M. Alf Museum of Paleontology. Located at the Webb Schools in Claremont, it's the only nationally accredited museum on a high school campus in the U.S. You may not know the name Millard Sheets, but you have definitely seen his work — and this is hardly the first time it has been displaced or destroyed.

Over the last three decades, his murals have been removed from buildings in Beverly Hills, Pasadena, San Jose and San Antonio, according to KCET. In Long Beach and Redwood City, they've been painted over. Sheets hasn't been around to witness this. He died in 1989 at age 81.

The Santa Monica mosaic's removal, overseen by Brian Worley, an art and restoration expert who Sheets mentored, should take more than two months. Then, it begins the journey to its new home, the Hilbert Museum of California Art at Chapman University.

To many, the mural's removal marks the end of a hard-fought battle to preserve the Home Savings Building, a Santa Monica landmark from an era when banks weren't just interchangeable stucco boxes but civic edifices meant to connote security, stability and a bedrock faith in capitalism.

"We feel extremely sad to lose this remarkable work of public art to a distant location," says Ruthann Lehrer, an architectural historian and member of the Santa Monica Conservancy. "Not only is it a tremendous loss to Santa Monica, but it forecasts the removal of the other artworks — the sculptures and stained glass — from this site, leaving a stripped down and dismembered building."

Beverly Hills-based real estate developer Mark Leevan, who has worked on different projects in Santa Monica, appears to have bought the building in the early 2000s. Since 2013, he has fought attempts to designate it as a historic landmark.

An Artistic Legacy

The importance of Millard Sheets to the California art world cannot be overstated. Born in Pomona in 1907, the precocious Sheets won his first art competition at the Los Angeles County Fair when he was 12. Theodora Modra, the fair's artistic director, became the boy's mentor. Sheets went on to study at the Chouinard Art Institute (the predecessor to CalArts) where he helped develop a new style of bold watercolor painting and won national recognition.

"All of a sudden, the East Coast artists realized that there weren't just Cowboys and Indians in California, there were artists," his son, artist Tony Sheets, says.

After an extended trip to Europe in 1929, financed by the winnings from a painting competition, Sheets settled back in Southern California, becoming a revered teacher and practicing artist. From 1931 to 1956, he served as director of fine arts at the Los Angeles County Fair (the Millard Sheets Art Center at the Fairplex is named in his honor). He also taught at Scripps College, the Otis Art Institute and helped design the L.A. County Seal.

Writing about a farewell exhibition of his work in 1943 (Sheets was going oversees as a correspondent for Life Magazine), Los Angeles Times art critic Arthur Miller explained Sheets' importance:

It's impossible to imagine the art of Southern California between 1929 and 1943 without Sheets and his influence. The joyous freshness of his work, the courage of his attitude towards art and life, and the power and intelligence of his teaching is a vitalizing spark behind the regional art development of these years.

Around this time, Sheets branched out into architecture.

According to his son, Sheets was approached by a contractor friend who had been tasked with building a training field in Chino for pilots. Sheets accepted the challenge and, after making a success of the venture, went on to design more than a dozen training schools across the West. He then began designing homes for his friends.

"He was an architectural designer not a licensed architect," his son explains. "He made a big point about that."

In 1953, the same year Sheets was appointed director of the L.A. County Art Institute (later Otis College of Art and Design), he was approached by banking magnate Howard Ahmanson, who was searching for an architect to design his new National Insurance Company Building on Wilshire Blvd.

"Have traveled Wilshire Boulevard for twenty-five years," Ahmanson wrote in a 1953 telegram to Sheets, included in the 2018 book Banking on Beauty: Millard Sheets and Midcentury Commercial Architecture in California, "Know name of architect and year every building was built. Bored... Need buildings designed."

Sheets accepted the challenge. The building, bold for the era, would set the template for Sheets' work for Ahmanson over the next three decades. The building and its art were uplifting and positive, mixing art deco elements with elements from Mayan architecture, Byzantine churches, mythological legends and old maps. It also featured stained glass windows depicting the history of banking.

Ahmanson was thrilled with the results. "It would be the prototype for the many Home Savings and Loan Buildings that Sheets would design for Ahmanson between 1954 and 1975," Tony Sheets and Janet Black write in A Tapestry of Life: The World of Millard Sheets. "The design of the buildings, which incorporated mosaic murals celebrating California life, represented Sheets' abiding view of the artist's responsibility to the public in adding beauty to life."

"Art is an expression of the love of a man as a human being," Sheets explained in A Tapestry of Life, "a special language born out of tremendous need that is universal. The artist's task now and in the future is to communicate this to mankind."

According to Timothy Sandefur in The Objective Standard, patrons of the new building felt the love:

Customers loved it and even wrote Ahmanson thank-you letters. "Whether I chose your establishment . . . for the very soul-lifting wall mural is an enigma even to myself," one enthused. Another thanked him for having "given Los Angeles beauty and strength where, unfortunately, others have contributed oblong boxes." When the bank sent a questionnaire to customers asking why they chose the Wilshire Boulevard branch, the most common answer was, "We like to be associated with something beautiful."

Over the next three decades, Sheets would design around 40 bank branches for Ahmanson, stretching from California to Texas. These monumental, geometric temples to capitalism celebrated the West as a cultural and financial center, a place of endless security and sunshine, built by the sweat of hearty American pioneers.

"The Home Savings buildings, which typically have a mural as the artistic centerpiece, have certain consistent features of design and materials which make them instantly recognizable," the Santa Monica Conservancy's Lehrer explains. "The architectural composition is simple, consisting of blocky masses, which are clad in travertine marble and trimmed with a textured gold band at the top."

Most important, each branch had art that celebrated the history of the area it served. The Sunset and Vine location had a mural about the history of movies. San Antonio told the story of the Alamo; Pasadena, the Rose Parade.

"He was very, very personable and he knew how to sit down with a potential client and pick out what the client needed," Tony Sheets recalls. "He would confer very much with clients and talk to them about their interests and their history and that sort of thing and then try and do artwork that shadowed that... It was a collaboration. That's one of the things that he taught me, that working in collaboration with the other people, whether it's another artist or the client or the contractor, you always get a better product."

A Perfect Partnership

Sheets' respect for collaboration and his willingness to learn spurred the continuous evolution of his work. "He loved the medium of mosaic but he wasn't really impressed with what was being done in the United States," his son says. "He traveled to Europe and went to the countries that had ancient mosaics and really, really got a feel for what can be done with tesserae and the little glass pieces."

Most of Sheets' iconic murals were designed along with his assistant, artist Susan Hertel, who had been his student at Scripps College. Sheets also employed many up-and-coming artists at his studios, including Nancy Colbath, who would execute "Pleasures Along the Beach."

The mural was the exterior centerpiece of Sheets' 25th Home Savings Building. "Santa Monica as a beach city is the theme of the artworks — the colorful mosaic on the facade, the sculpture of a child riding on a dolphin at the east entrance and the stained glass," a press release from the Santa Monica Conservancy explains. "The family groupings in the art convey the connection between the bank's services and family values. Home Savings indeed provided loans for residential construction and mortgages that fueled the post-war housing boom."

The Home Savings Building and its mural are Ruthann Lehrer's favorite work by Sheets.

"The mosaic mural achieved a new level of artistic brilliance, compared with other Sheets' murals, which were often smaller and less colorful," she says. "The large scale of the mural, its dazzling colors and design, its diagonal placement at the prominent corner of 26th and Wilshire, and the subject matter of a beach scene made it a cherished part of Santa Monica's streetscape and an icon to many residents."

The building remained a bank until 1998 when it was taken over by a retail tenant (it currently houses a New Balance store). The trouble began in 2013 when the building was approved for landmark designation by the Landmarks Commission. Leevan contested the designation.

In 2016, the City Council reversed the decision of the Landmark Commission on a technicality. The Landmark Commission did not approve the status a second time. The Santa Monica Conservancy appealed that decision. At a raucous council meeting in November 2016, Leevan's attorney, Roger Diamond, argued that the building and mural were not landmarks. As the kicker, he played a 1989 recording of an elderly Sheets saying that the mural was only "satisfactory" and that "I wince every time" driving by.

The City Council again granted the site local landmark status in 2017 but revoked it in September 2018. Instead, Santa Monica paid Leevan $250,000 in damages, and he agreed to remove the artwork and donate it to a nonprofit or the city. The city, it seems, never intended to take the art, hence its new home in the city of Orange.

According to Ruthann Lerher:

"The circumstances surrounding the landmark designation and subsequently the removal of landmark status for this building were unique, and were based upon procedural flaws in the City's process, rather than the merits of the building, or the public interest in keeping it here in Santa Monica, intact as a unified work of art and architecture It is not uncommon for significant buildings to be designated as landmarks over an owner's objection; but that action is usually followed by an owner gaining an understanding of the benefits of designation... that the regulations are not nearly as onerous as they believe. The Santa Monica Home Savings debacle is viewed as an outlier by the historic preservation community, since throughout the region many of these buildings have successfully been adaptively reused for new purposes."

While Leevan has become a villain to many in the preservation community, Sheets' son takes a more pragmatic view. "I don't get into the politics of a city like Santa Monica," he says. "Anyway, after all the fooling around and goofing off, the owner said, 'OK, I'll donate it.' And when they contacted me, I've been kind of partially involved in the background of that."

This isn't the first time Tony Sheets, who sees himself as the gatekeeper of his father's work, has dealt with the deconstruction of Millard Sheets' art. To him, it's simply the flow of progress.

"Things change," he says. "That's a small building on a big lot and the owner of the building wants to build a bigger building, which I understand. But he's been totally part of setting aside the time and the money. He's paying for the removal of all the art on the building, which is substantial."

An accomplished artist himself (he designed the famous "L.A. Evolves" concrete relief at 333 S. Spring St.), Tony Sheets has spent years preserving his father's endangered work. "I've saved murals in Texas and California. I've saved eight murals, painted murals, and all but one has been reinstalled," he says.

That fact is cold comfort to historic preservationists in Santa Monica. (Both Beverly Hills and Pasadena have managed to keep displaced Sheets' works in their towns, according to the Santa Monica Lookout.) The heated rhetoric surrounding the fate of Santa Monica's former Home Savings Building is something the elder Sheets probably would have abhorred. "He listened," Tony Sheets says of his father, the great collaborator, "which is very important."

-

Restored with care, the 120-year-old movie theater is now ready for its closeup.

-

Councilmember Traci Park, who introduced the motion, said if the council failed to act on Friday, the home could be lost as early as the afternoon.

-

Hurricane Hilary is poised to dump several inches of rain on L.A. this weekend. It could also go down in history as the first tropical storm to make landfall here since 1939.

-

Shop owners got 30-day notices to vacate this week but said the new owners reached out to extend that another 30 days. This comes after its weekly swap meet permanently shut down earlier this month.

-

A local history about the extraordinary lives of a generation of female daredevils.

-

LAist's new podcast LA Made: Blood Sweat & Rockets explores the history of Pasadena's Jet Propulsion Lab, co-founder Jack Parsons' interest in the occult and the creepy local lore of Devil's Gate Dam.