- India

- International

The other Ayodhya trial: Case against LK Advani, Murli Manohar Joshi, Uma Bharti is crawling

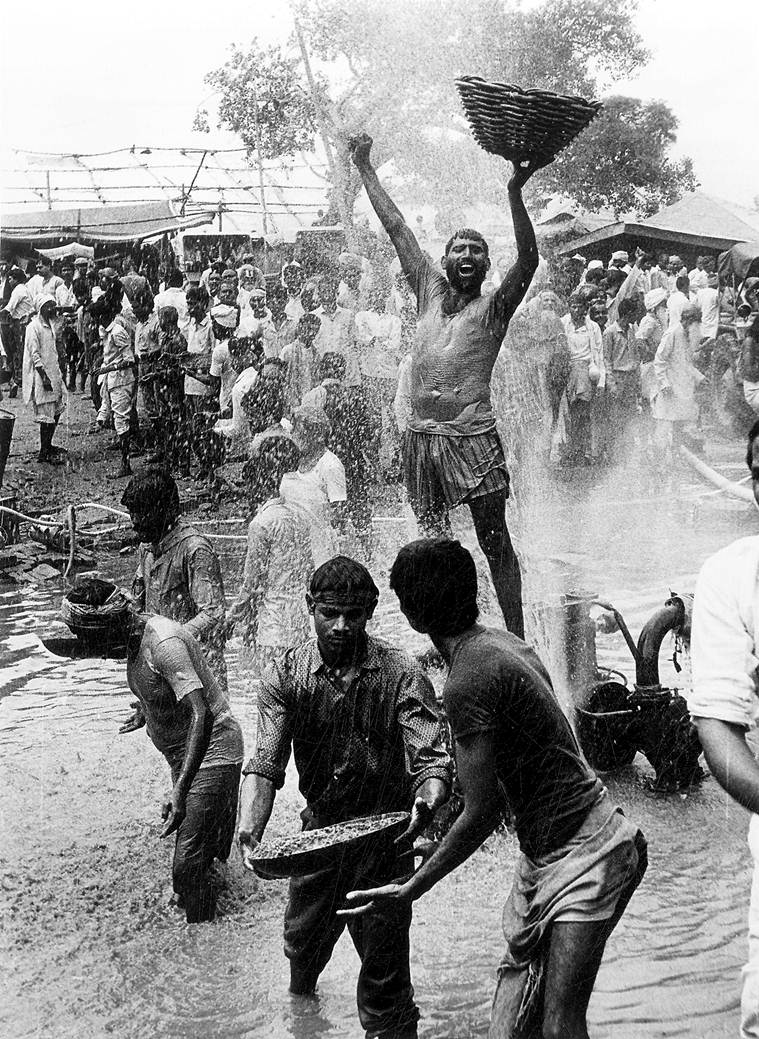

As SC begins daily hearings in Ram Janmabhoomi dispute amidst national spotlight, the criminal trial in the Babri Masjid demolition, against L K Advani, Murli Manohar Joshi and Uma Bharti among others, is crawling. The Indian Express spends a day at the Lucknow trial where an overburdened judge is racing against time, as well as decaying evidence, and ailing, lost or dead witnesses

Atop the Babri Masjid before its demolition on Dec 6, 1992. Express Archives

Atop the Babri Masjid before its demolition on Dec 6, 1992. Express Archives

On August 5, as the Supreme Court began its daily hearings in the civil case in the Ram Janmabhoomi dispute, a special judge took his place unobtrusively 550 km away, in a dimly lit, empty room, with stacks of decaying papers, in the Old High Court complex in Lucknow. Without a battery of senior lawyers, curious visitors or national media swarming the corridors, and with a lone Constable, Shatrughan Singh, chasing boredom away at the door, there was little to indicate that in this room was on one of India’s most-anticipated criminal trials — apart from a small, chipped wooden board at the door declaring ‘Ayodhya Prakaran (episode)’.

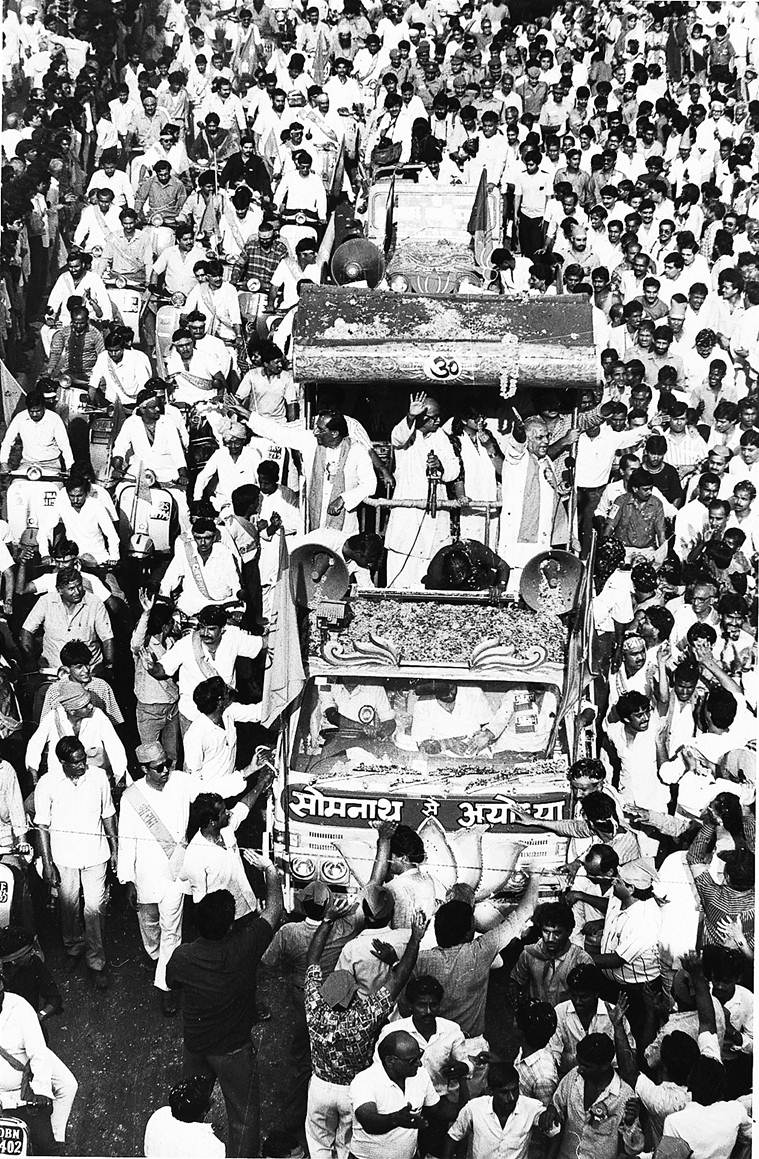

The criminal trial, to fix liability of those who conspired and brought down the Babri Masjid on December 6, 1992, covers two separate cases — FIR No. 198 against senior BJP leader L K Advani and seven leaders of the Sangh Parivar, including Murli Manohar Joshi and Uma Bharti, for making incendiary speeches; and FIR No. 197 against “lakhs of unknown kar sevaks” for tearing down the mosque. The kar sevaks also face charges of dacoity, promoting enmity between religions, robbery and rioting.

Like the civil case, which the Supreme Court said last week it would be hearing five days a week (breaking a convention), this criminal case too has been “fast-tracked” several times by the apex court. It now has a time limit of April 2020.

But, like the civil case, the criminal trial too is racing against a deadline of another kind. If in the Supreme Court, the bench is headed by Chief Justice of India Ranjan Gogoi, whose retirement in November could necessitate hearings all over again if the judgment is not delivered by then, Special Judge S K Yadav, who is hearing the criminal trial, is on an extension past his retirement on September 30.

Watershed cases

Like the Supreme Court trial in the century-old civil case over the Ram Janmabhoomi dispute, the criminal trial in the Babri Masjid demolition may have entered its fast lap. While the two decisions would be independent of each other, both would be watershed in India’s legal history in determining how religion and politics interact with the law.

The judgment in one case would have no bearing on the other.

But this muggy August morning, little of this urgency is evident at the District and Sessions Judge courtroom in the Old High Court complex. Since Judge Yadav is also the administrative head of the district court since November 2018, there are other cases and managerial duties requiring his attention. The Babri trial moves to the special courtroom reserved for it only when the court has to examine video or audio evidence. Most days, Judge Yadav hears the arguments in the main courtroom, which is the busiest in the complex, with fresh cases being listed before it.

Read | Hindus believe Ayodhya is Ram’s birthplace; court shouldn’t go beyond to see rationality, SC told

Atop the Babri Masjid before its demolition on Dec 6, 1992. Express Archives

Atop the Babri Masjid before its demolition on Dec 6, 1992. Express Archives

Today, amidst hearings in the Babri case on one end of the podium, on the other side, a clerk is furiously typing away the testimony of a woman, who is sobbing quietly recollecting how her nephew bludgeoned her husband to death under the influence of alcohol.

The first to arrive at the court is former police officer S P Singh, dot at 10 am. Retired in 2015 and now settled in Delhi, Singh was a Deputy Superintendent of Police posted in Lucknow in 1992 and, as part of the CBI team investigating the demolition, seized certain documents that the agency hopes to use as evidence. Some of those documents are prescriptions and medical records of those injured in the incidents of December 6, maintained by the medical camp set up by the Uttar Pradesh government then.

Singh’s cross-examination is scheduled for 11 am. However, the defence team does not show up, and the court has no information why.

Judge Yadav goes about his day, hearing other cases.

At 3 pm finally, advocate Abhishek Ranjan, who mainly represents VHP leader Champat Rai Bansal, turns up and asks for the judge’s permission to examine the prosecution witness. After borrowing the prosecution’s set of documents, he begins questioning Singh.

“The defence deliberately begins the trial this late so that they can delay the proceedings,” prosecution lawyer R K Yadav, representing the CBI, laments. The judge does not react.

Standing at one end of a long raised platform before the judge, S P Singh answers Ranjan’s questions, which all begin with “Kya yeh kehna sahi hoga ki (would it be correct to say that)…?” Singh is expected to reply in a yes/no first, and then explain. The elaborate answer is to be then condensed, translated into legalese and dictated to the clerk by the defence lawyer himself.

Copies of the deposition are not public records and not attached to the verdict. Judges quote relevant paragraphs from the depositions to substantiate the conclusions that have been drawn.

It is by now 4 pm, and a court staff begins bringing piles of files for Judge Yadav to sign, who clears them even as he is trying to hear witnesses in the murder case as well as the Ayodhya case simultaneously. The files range from sanctioning leave of judges to allotting cases to them.

L K Advani on Somnath to Ayodhya Yatra, leading up to the razing of the mosque. Express Archives

L K Advani on Somnath to Ayodhya Yatra, leading up to the razing of the mosque. Express Archives

At regular intervals, CBI lawyer R K Yadav objects to the questions posed or the dictation. Judge Yadav continues to sign administrative files until the argument between the prosecutor and defence lawyers grows loud enough to demand his attention.

At 5 pm, the court rises for the day, with the cross-examination spilling over to the next day.

S P Singh would eventually take three days to record his testimony.

The criminal trial began in 1992. In the nearly three decades since, 134 witnesses as well as eight of the 48 accused have died, over a hundred witnesses are now “untraceable”, and 40 either too old or too sick to appear before the court to testify what they saw on December 6, 1992. In 2017, the CBI list had 1,026 prosecution witnesses, with only about 200 having deposed since the trial began in 1992.

Two years later, the number of prosecution witnesses examined by the court stands at 291, almost entirely journalists and police officers who investigated the case. About a month ago, the CBI moved an application saying it will not produce any further witnesses. So, now, at least 10 more witnesses are expected to be produced, before the court starts the examination of the accused.

So far, the accused, including Advani, have personally appeared before the court only when the charges were to be framed against them, in 2017. However, the hearing was not held on the court premises but in the conference room of a management college in Lucknow.

In the list of VIP accused, VHP leaders Giriraj Kishore and Ashok Singhal are among those dead, with the proceedings against them abated.

Read | At 92, key face in Ayodhya case K Parasaran is a trusted voice of many governments

The defence’s main line of argument is that the then P V Narasimha Rao-led Congress government instructed the CBI to build a case against top BJP leaders and fabricate evidence for political gains.

For the 13 accused, lawyers K K Mishra and Mankeshwar Tripathi, apart from Abhishek Ranjan, appear. On paper, Ranjan represents VHP leader Bansal, but he cross-examines the witnesses on behalf of all the accused. “It’s the same case and the same arguments work for all the accused. There’s no need for many lawyers,” Ranjan says.

Rapped by the Chief Justice of India as recently as August 13 for failing to meet “judicial standards” in cases involving political leaders, the CBI has been struggling to stitch its Ayodhya case together, in more ways than one. In 2017, two members of the prosecution team, K S Negi, the CBI officer who assists the prosecutors, and Lalit Singh, one of the two special prosecutors, had an accident while driving back from Ayodhya after picking up some documents. Both were severely injured, and appeared for subsequent court hearings in bandages and leaning on sticks.

Singh still walks with a limp, which makes it difficult for him to step onto the podium during arguments.

CBI teams have had trouble locating witnesses, with many changing addresses. In other cases, the CBI has traced an address only to find the witness dead. Of the 134 witnesses for whom death certificates have been filed, the CBI has had to itself obtain certificates in case of at least 15 since the kin of the deceased had not applied for the same.

Despite the Supreme Court monitoring, there have been days when the Special Court has not functioned for the day as summoned witnesses have failed to show up. As per the law, the prosecution can seek warrants against such witnesses. However, court records show the CBI has not made any such application so far.

The defence has said in court that many witnesses have requested to be relieved. “There is a professional risk to deposing now, after 27 years. If a court ruling records that a journalist is not credible as a witness, it damages her entire career,” defence lawyer

K K Mishra points out. What he leaves unsaid is that in a criminal trial, the defence lawyer’s endeavour is to discredit prosecution witnesses by highlighting inconsistencies in their testimonies.

The prosecution has been raising this, saying that testifying journalists are being asked to recall minute details from 26 years ago such as the precise time they saw the first kar sevaks on the dome of the Babri Masjid, the specifics of the cameras they were carrying, and their bills for the travel and stay in Ayodhya.

While the prosecution says this only dissuades journalists from testifying, Mishra scoffs, “Those who participate in holding remembrance meetings on the anniversary of the dispute say they don’t remember the specifics of the case in cross-examination!”

The CBI’s case is weak on another account. While apart from the testimonies of eyewitnesses, it is largely built on the footage of the incident, in all these years, it has not obtained a single forensic report clarifying whether the video evidence is raw footage or edited. “I can tell you what the CBI has done. I cannot answer why it has not done something,” says Negi.

The VCRs (video cassette recorders) submitted to the court have been in the same box in evidence rooms of the Special Court for over two decades. The cassettes were not sealed when they were seized at ground zero or subsequently. Despite VCRs now being largely obsolete, neither have they been digitally stored nor converted to a different format.

“Ask the CBI why they are only relying on the tapes given by journalists. A lot of these tapes were edited in the newsroom. How can any court rely solely on that?” Ranjan asks.

The courtroom has witnessed at least six incidents where the tapes could not be played for technical reasons. “In one of the testimonies, they played a video that showed the demolition for the first few seconds and then suddenly an interview of Manmohan Singh popped up on the screen,” a court staff who did not wish to be identified recalls.

To ensure that the Ayodhya criminal trial was not derailed due to change of the Special Judge, the Supreme Court resorted to an unusual move in July. It invoked its powers under Article 142 of the Constitution, which allows it to pass any order to ensure complete justice, and extended Judge Yadav’s retirement date by six months from September 30. Yadav was an Additional District Magistrate in April 2017 when appointed Special Judge for the Ayodhya case. Now, when he retires, Yadav will focus solely on this case and will be relieved of his administrative roles.

The trial against unknown kar sevaks began initially in Lalitpur in Uttar Pradesh. The state government transferred the case to Lucknow in September 1993 when Uttar Pradesh was under President’s rule. The other case, against political leaders, was transferred a month later and the CBI filed a consolidated chargesheet in 1995.

As governments changed both at the Centre and state, the court made no progress till 2017. In April that year, the Supreme Court revived the criminal trial in the demolition case by allowing the CBI to add a fresh charge of criminal conspiracy against BJP leaders, including Advani, Joshi and Uma Bharti. In a 40-page decision, Justices

P C Ghose and Rohinton F Nariman also set a two-year deadline for the court to complete the trial, and added for good measure that the Special Judge could not be transferred until the trial was completed.

The Supreme Court also berated the CBI for allowing a “fractured trial” till then and said it would monitor the proceedings now. “We grant liberty to all parties to approach us in case our orders are not fully followed in letter and spirit,” the Supreme Court said.

So, the renewed trial began in June 2017, with two years to frame charges, as well as to examine over a hundred prosecution witnesses. Each of the accused was granted bail on the condition that they furnish a bond of Rs 20,000.

In June this year, Judge Yadav sought more time to conclude the trial, and a month later, the Supreme Court extended the deadline by another nine months.

This week, the examination of the prosecution witnesses is expected to end. The court will next move to question the accused as per Section 313 of the CrPC, who will then be given an opportunity to reply and be allowed to bring their own witnesses and lead evidence.

Finally, both sides will argue on the evidence before the judge can pronounce the verdict. If all goes well, that would be six months from now.

However, a key development is expected on September 4 that could extend this timeline once again. That day, the accused No. 3 in the chargesheet, Kalyan Singh, under whose tenure as Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh the Babri Masjid was razed, is set to demit office as the Governor of Rajasthan. Since he is entitled to immunity under the Constitution as long as he holds the post, the Supreme Court in its 2017 order had directed the Special Court to “frame charges against him as soon as he ceases to be Governor”.

Which means the process will have to be repeated for Kalyan Singh, including framing of charges, examination of new witnesses and arguments against the evidence.

In short, another delay.

Apr 27: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05