I could tell you that I fell in love with boxing the first time I walked into a gym, but the first boxing gym I ever went to was in point of fact, an Edwardian bandstand.

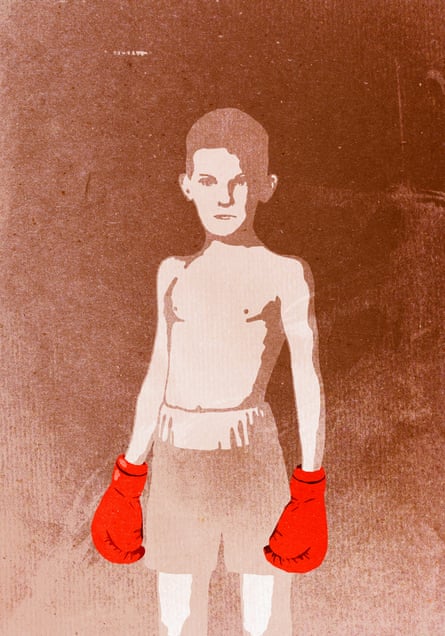

Fritzy was going to train my friend David and me at a local park; an elegant cricket ground ringed by bowing fig trees. I arrived half an hour early, a move I would later recognise as a classic symptom of nerves. I was worried Fritzy would find me wanting in some fundamental way; that he’d somehow know I hadn’t been in a fight since I was seven and that my mum still gave me a kiss on the cheek on my way out the door each morning.

It was six in the evening, early spring and not yet warm. Behind me, down a small hill, the sun set over the fig trees while games of touch football ebbed and flowed on the field. I waited in the rotunda, elaborately casual as I leaned on the rail and surveyed the street for a guy who looked like a boxing trainer. It felt like the lead-up to a blind date.

Fritzy arrived, driving a compact SUV. I would have known it was him even if he hadn’t been lugging an enormous duffel bag overflowing with gloves and headgear. Despite his age and height—he was in his 50s and a good six inches shorter than me – Fritzy’s physical presence was intimidating. Broad across the shoulders, he was dressed in athletic shorts, runners and a dark T-shirt that hung over a modest paunch. His boyish face was pugnacious but not battered-looking, with a lantern jaw, a slight underbite and narrow, heavy-lidded eyes.

He sauntered up to the bandstand, yelled a greeting and flashed a wolfish smile as he slapped his hand into mine. His grip, unsurprisingly, was firm. Waves of dark green ink washed down his forearms, lapping at his wrists.

“How are yaz? Ready to learn to fight? Don’t you worry. We’ll teach you how to throw punches. BANG. BANG. BANG.”

I was a little taken aback by the enthusiasm, but there was no time to be awkward. With his bandsaw voice and rapid-fire delivery, Fritzy hardly let us get a word in edgeways. Before I knew it, he had set a small rectangular kitchen timer with a digital screen – the same type that hung on the door of my mum’s oven – for 10 minutes and we were jumping rope, right there in the rotunda.

“I like my boys to skip for 10 minutes, sometimes 20, before every training session,” he said over the sound of our ropes clicking on the tiles. Given my level of fitness, this seemed about as feasible as running the New York marathon. After a few minutes, despite the breaks I took every few rotations to untangle myself, my calves, shins, shoulders, lungs and lower back were radiating pain.

I kept whipping myself on the back and triceps, which left the skin criss-crossed with painful red stripes. I looked more like a galley slave than a boxer. I was ready for the session to end before it had properly started and Fritzy, who must have realised what he was dealing with, called time early.

He asked if we’d brought wraps. I nodded and retrieved the black cotton rolls from my bag.

The idea of bandaging hands has been around almost as long as boxing itself. The ancients knew that when an unsupported human fist hits something hard, like, let’s say, a human head, the force of the impact can cause the hand to collapse and the wrist to bend. It can even snap the metacarpal bones that run through the palm, an injury I am told emergency room doctors refer to as “the dickhead fracture”, so common is it on Friday and Saturday nights.

The Greeks worked out a way to protect boxers from these ignoble injuries, using strips of cloth to lock the wrist in place and compress the tissues of the hand. In turn, and as they were wont to do, the Romans took hand-wrapping to a degenerate extreme by having gladiators wear caestuses, leather, wood and metal straps that were basically giant brass knuckles and could kill with a single blow.

That sort of thing is frowned upon these days. Still, when Fritzy asked how my wrapped hands felt, and I said “good”, what I meant was that it felt like he had transformed them from everyday implements into deadly weapons. I ground my right fist into my upright left palm like a cartoon bully, rotating it, enjoying the power flowing from my knuckles.

Fritzy instructed us to “shape up” – get in a boxing stance – with our legs shoulder width apart, our right feet back and our hands up. We did so to the best of our ability, which, Fritzy made clear, was not all that well. He walked between us, inspecting our postures and making small adjustments by grabbing and manipulating our hands and shoulders, as if he were posing two giant action figures in a strange suburban diorama.

Once we were arranged to his satisfaction, Fritzy delivered a lecture about the importance of keeping our hands up. He illustrated this by lunging at me and slapping me on the right fist. I blinked.

“And what happens if ya don’t keep ya hands up?”

Ever the teacher’s pet, I started to answer before I realised the question was rhetorical: “Well you’d get hi…”

Fritzy slapped my hand again, knocking it into my chin and shutting me up. Fair enough.

Next up was the left jab. “That’s ya stick,” said Fritzy, thrusting his left hand into the air before our faces. “A guy gets too close … boom. Ya wanna come in … boom. Ya wanna see where he is … boom.” With every boom he poleaxed an imaginary opponent.

Now he waved us on to follow him. Feebly, we began to shadow-box, tottering around like a pair of newborn giraffes. All the while Fritzy yelled pointers and feigned punches at us. Despite the animated tuition and my own best efforts, Fritzy’s defiant spearing motion emerged from my body as a gentle pawing. If this was shadow-boxing, there was a real possibility my shadow might win.

The root of the problem was the fact that in boxing, a right-handed (orthodox) fighter uses his left hand to do the hard work of jabbing and hooking while his dominant hand lounges about, waiting to be used for heavier right crosses. The same process applies in reverse to left handers, although because southpaws have always been considered a bit freaky and suspect (despite the natural advantage of being rare and difficult to get used to) some are taught to box in the orthodox stance. I’m not the most coordinated person at the best of times and having to rely on my non-dominant hand seemed not only counterintuitive, but cruel.

Fritzy soon progressed to right hands, and we followed suit, stumbling around like drunks trying to pass a field sobriety test. Every new instruction was accompanied by miming, swearing and exuberant onomatopoeic outbursts: bang for crashing single punches, bing bang for one-twos, even bada bing bang bong for combinations.

Perhaps it was the sound effects, but the sense of invincibility the wraps had engendered was wearing off. I was starting to feel self-conscious, a sensation that our position on a raised platform in the middle of a quiet park did nothing to alleviate. Even worse was the stream of haughty labradoodles and French bulldogs walking their owners past the rotunda – owners who, I was horrified to note, would occasionally stop and crane their necks to get better look at whatever was going on inside.

I was not given the chance to wallow in my discomfort. Fritzy reached into his duffel bag and removed a pair of black focus mitts, then helped us to pull on our gloves. Then he stood in the centre of the rotunda with David and me facing inward towards him on opposite sides. He fiddled with the buttons of his kitchen timer and again placed it on the tiles. Then he called for me to start punching: 30 seconds of uppercuts, aiming for the white circles in the middle of his mitts.

“One, two, three, four, one, two, three, four. That’s it,” he cooed. “A little bit harder now. A little bit faster now. Thaaat’s it. Come on.” When the 30 seconds was up, he’d rotate 180 degrees and put David through the same process. For some this might have been unsatisfyingly brief, but at this point 30 seconds was about the most cardiovascular stimulation I could handle at any one time.

The gloves started shedding stuffing as soon as they made contact with the pads. But the thrilling sensation of impact overwhelmed everything: the disappointment about my crappy gear, my embarrassment about the whole bandstand situation, my fatigue. Hitting the pads, I felt the expression of the potential in my wrapped hands. The crack of leather on pleather echoed around the rotunda. Each collision with the pad ran down the back of my clenched fist and up my arm like electricity. I felt surprisingly competent, even dangerous, as we moved to jabbing and then combinations. Of course, Fritzy was doing almost all the work, bringing the pads crashing down onto my fists. But I didn’t know that at the time. All I knew was I felt like Mike Tyson. And to be fair, Fritzy didn’t do much to disabuse me of this notion. Not only did he offer an encouraging oof whenever I even came close to hitting the centre of the pad, he kept shaking out his hands, as if my badly placed and mistimed blows were too powerful to absorb.

Eventually, the little kitchen timer beeped. I looked around. It was dark. My first boxing lesson was over. Exhausted, David and I shook hands with Fritzy and walked down the steps of the bandstand, past the flower beds to our parents’ cars. My T-shirt and shorts had long ago soaked through and sweat was running down my legs into my shoes. It looked – and felt – as if I’d jumped into a heated swimming pool in my gym clothes. I wasn’t sure I’d be able to drive home.

“Boom, bang, crash. That was fun,” said Dave. “Want to do it again?”