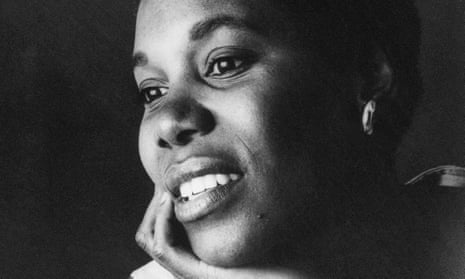

The distinctive contribution of the novelist Paule Marshall, who has died aged 90, was to express the interaction between Caribbean and African-American identities, drawing on her Barbadian background and life in her native New York. She wrote eight volumes of fiction, and in 1989 received the Dos Passos prize for American creative writers who have produced work in which is evident “an intense and original exploration of specifically American themes, an experimental approach to form, and an interest in a wide range of human experiences”.

The novel that received the most critical attention was Praisesong for the Widow (1983), which focused the themes of historical and personal development in the person of Avey Johnson, a middle-aged widow whose journey to a small Caribbean island enables her to begin questioning her repression of joy and affection in her struggle to acquire a white bourgeois-defined respectability. This book dramatised a continuing theme in Marshall’s fiction: the need to set aside materialistic and individualistic values in order to find spiritual and psychological fulfilment.

Marshall described herself as a “very slow, painstaking, fussy writer”, and would spend up to 10 years on the completion of a novel. An activist in the civil rights and anti-Vietnam movements of the 1960s, she felt a responsibility to write for the benefit of the community, revealing her readers to themselves truthfully and thus empowering them. However, she differentiated herself sharply from other black female writers, remarking in an 1982 interview that she felt it important to create “ordinary” protagonists who did not “go through all those terrible things that are supposed to happen to black people, to young black women”.

A female character created by Marshall, she said, “is not raped by her father, or her stepfather, or her mother’s boyfriend, she does not witness physical brutality between her mother and father, she is not, in other words, a social statistic”. Marshall thus dismissed in turn representations of black female experience by Alice Walker, Toni Morrison and Maya Angelou.

She was born Valenza Pauline Burke in Brooklyn and grew up in a largely West Indian neighbourhood, the daughter of Ada (nee Clement) and Samuel Burke, who had emigrated separately to New York from Barbados just after the first world war. Her father worked in a mattress factory after arriving illegally in America as a stowaway from Cuba, but during Paule’s childhood abandoned the family to become a disciple and preacher for Father Divine’s religious movement; her mother worked as a maid for a wealthy white woman. At the age of nine, Paule spent a year with her grandmother in Barbados, a visit which influenced much of her later writing.

Her first novel, Brown Girl, Brownstones (1959), recorded in lyrical and expressive language the idioms and attitudes of New York’s Barbadian community, and particularly the group of women who would gather in her mother’s house after a hard day’s work. Marshall paid tribute in a later essay to these “poets of the kitchen”, saying: “They taught me my first lessons in the narrative art. They trained my ear. They set a standard of excellence. This is why the best of my work must be attributed to them; it stands as testimony to the rich legacy of language and culture they so freely passed on to me in the wordshop of the kitchen.”

The novel portrays the conflicts within that community, and between the mother’s determination to save money and buy the family’s rented house and the father’s longing to return to the less restrictive society of Barbados. Marshall also drew on the rich legacy and culture of other writers, and as a child read Dickens, Thackeray and Fielding. Her discovery of the African-American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar inspired her to become a writer and to adapt her middle name to to give a pen-name of Paule (with a silent “e”).

The title of her collection of novellas, Soul Clap Hands and Sing (1961), in which all four stories focus on elderly and unhappy men who seek in vain to change, reveals her familiarity with Yeats (its title comes from a line of his poetry). Later she wrote of her admiration for Thomas Mann, and his ability to combine an individual story in the context of a community’s history.

Her ambition to emulate Mann is seen in The Chosen Place, The Timeless People (1969), claimed by one critic to be among “the four or five most impressive novels ever written by a black American”. Set on a fictional Caribbean island, the novel draws together characters and cultures from Africa, the US and the Caribbean, as well as China and India.

In the 1950s and 60s Marshall worked as a journalist and librarian. Following the success of her first two books she was selected by the poet Langston Hughes to accompany him on a tour of Europe in 1964. She taught creative writing and English literature at Virginia Commonwealth University, in Richmond, Virginia, as well as at Yale, Oxford, Columbia and Cornell universities, and was from 1997 Helen Gould Sheppard professor in literature and culture at New York University. She retired from teaching in 2009.

The Fisher King (2001), her last novel, set in the 1940s Brooklyn of her youth, won the Black Caucus of the American Library Association literary award. In 2009 she published a memoir, Triangular Road, based on a series of lectures delivered at Harvard and in the same year received a lifetime achievement award from the Anisfield-Wolf book awards.

She married Kenneth Marshall in 1950 and Nourry Menard in 1970; both marriages ended in divorce. She is survived by a son, Evan, from her first marriage, and a stepdaughter, Rosemond, from her second, and by two grandchildren.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion