India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi has pursued an “Act East Policy,” intended to strengthen Indo-Pacific strategic relationships, regional political stability, and economic exchanges with Myanmar and other members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, or ASEAN. Stronger ties require stabilizing the region near India’s northeast border with Myanmar. India’s state of Manipur, with about 2.75 million people, borders Myanmar and is home to three major cross-border ethnic groups with insurgencies. Success in that state could spread to others including Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland and Mizoram, explains Brandon J. Miliate, librarian for South and Southeast Asian Studies at Yale University. So far, insurgent groups have hampered India’s efforts to develop the border city of Moreh and trade. Roads are not enough, and Miliate suggests that long-term solutions require agreement of three major ethnic communities. India compounded uncertainty for the region over the past decade with reliance on secretive bilateral negotiations with each group, slow follow-up on specific political arrangements, failure to ensure disarmament or end ongoing collection of payments from local communities. Miliate concludes with what is needed: “inclusive negotiations to foster collective solutions for all of Manipur’s diverse communities” and “devolution of power from the state capital, Imphal, to district capitals.” – YaleGlobal

India’s Act East Policy and Manipur

India aims to strengthen ties with Myanmar and ASEAN, but struggles with development, trade and stabilization in its own northeastern states Brandon J. MiliateThursday, September 5, 2019

NEW HAVEN: The Narendra Modi–led Bharatiya Janata Party has been adept in coining slogans and winning public approval in India. But its policies for looking and acting east to woo the rest of Southeast Asia have been uneven.

In the 2019 General Election, the BJP won the majority of votes in Manipur’s Imphal Valley, further marking the political differences for the predominantly Meitei, Imphal and the surrounding Kuki/Zomi and Naga mountainous areas of the state, not to mention neighboring Nagaland and Mizoram. Despite these small inroads into the Northeast, Modi’s government has done little to assuage this conflict-prone region or transform the region into a major site of economic exchange with Southeast Asia.

Immediately after taking power in 2014, Prime Minster Modi’s administration changed the previous government’s passive-sounding “Look East Policy” to a reinvigorated “Act East Policy.” This policy is supposed to support India’s efforts to increase political and economic exchanges with neighboring Southeast Asia. Central to these efforts is the recasting of India’s restive Northeast as the gateway to Myanmar and the rest of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

Action verbs aside, New Delhi is still a long way from offering meaningful solutions to the problems of the Northeast, and the government has done little to leverage the strengths of this dynamic region. The instability and insurgent violence, while abated in recent years, remains the single largest hurdle to development in the Northeast. Peace-building efforts might offer temporary stability, but have done little to address the real political demands of the area’s diverse peoples.

Manipur, the erstwhile jewel of India, is central to the future of India’s Act East Policy, and the policy choices India makes here will make or break the wooing strategy. Events in Manipur are key to the other three states that border Myanmar: Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, and Mizoram, with ethnic kin and affiliated political movements in each. Despite dreams of an economic hub, insurgent actors still exercise significant power in the state, especially in the border cities, and New Delhi has not yet offered realistic solutions to demands for ethnic self-determination in the region.

The fate of Moreh, a small town on the Manipur-Myanmar border, is instructive. New Delhi is planning to build profitable trade with Southeast Asia through Myanmar as part of the Asian Highway Network. New office buildings and customs departments are being built on the outer edges of the town; a “smart” hotel heralds the hope of more high-profile visitors. Security is on everyone’s mind, and visitors and residents alike pass three to five checkpoints to enter the city and building sites from Imphal.

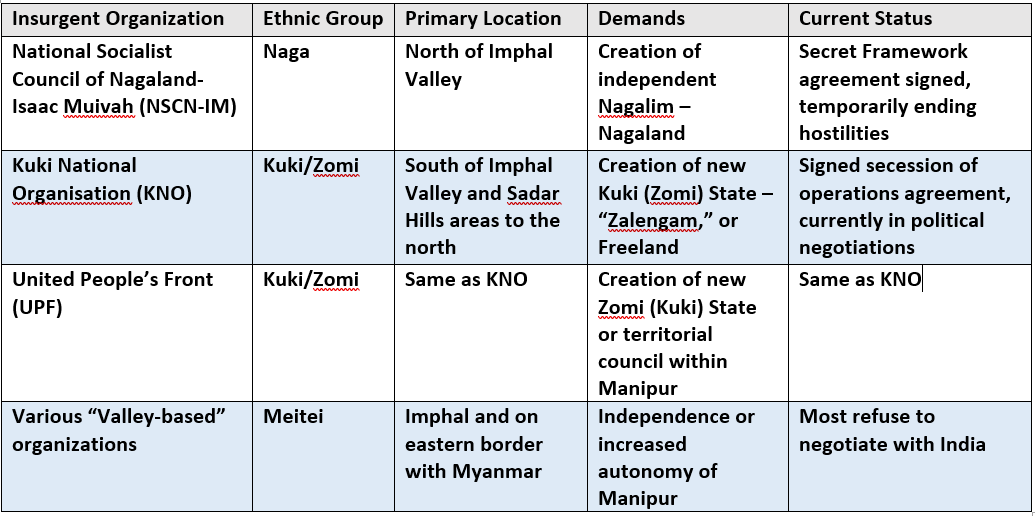

Despite the illusion of security, Moreh is host to a myriad of insurgent organizations from all three of Manipur’s major ethnic commuities: Meitei, Kuki/Zomi and Naga. Cadre from the Kuki National Organization, KNO, line the road and guard small wooden cabins, no more than 20 meters from the last checkpoint. They are well-armed and ready to protect “no-man’s land” – an un-demarcated tract between Moreh and the neighboring Sagaing Region of Myanmar. It is hard to imagine that this border crossing will ever open and even harder to imagine that the KNO would allow it to remain open if their demands for a Kuki state aren’t met. Other insurgent organizations include the United People’s Front, UPF, and the National Socialist Council of Nagalim-Isaac Muivah, or NSCN-IM. Moreh, rather than being a stable area for cross-border trade and exchange, is a microcosm of Manipur and the Northeast more broadly.

NSCN-IM and affiliated civil society organizations affect to represent the interests of the Naga peoples across India and Myanmar, and fight for the creation of a united and sovereign Nagalim. Currently, NSCN-IM is the largest insurgent organization operating in the state. The creation of Nagaland, carved out Assam in 1963, did little to calm the conflict and served as catalyst for the Naga insurgent groups to move their attention south to Manipur. NSCN-IM’s territorial claims are extensive, including the hill areas surrounding Imphal Valley as well as Kuki/Zomi and Meitei territories.

The Kuki/Zomi insurgent groups are divided into two umbrella organizations, the KNO and UPF. They spend as much time fighting each other as Indian security forces. Their territorial claims are less extensive than those of the NSCN-IM though still include substantial proportions of the northern hills. The proposed new state of Kukiland/Zalengam would surround the Imphal Valley.

India may have largely reduced the valley-based Meitei insurgent groups to small gangs, responsible for little more than occasional IED blasts on rural roads or police stations, but they still exercise significant power in the state, where Meitei communities feel increasingly vulnerable, at the mercy of the mountain-based insurgent groups and the Government of India. These insurgent organizations are fighting for increased autonomy along with the independence of Manipur.

Any long-term solution to the insurgency in Manipur requires the agreement of all three ethnic communities. However, the Government of India continues to pursue a number of detrimental policies in Manipur. Rather than seeking a mutually agreeable solution to address their demands, New Delhi has relied on secret bilateral negotiations with each armed group or ethnic community. This strategy has inflamed suspicions and set the stage for increased anxiety and uncertainty in the region. For example, the framework agreement with the NSCN-IM has still not been made public, even as the group uses this as a recruiting tool and intimidation tactic against Kuki neighbors.

Likewise, the step-by-step process of framework, succession of operations, ceasefire and political agreement has proven too slow and problematic in Manipur where internal divisions can take shape in the years between talks that threaten previously hard-won progress. When all Kuki/Zomi organizations signed a succession-of-operations agreement in 2008, meaningful political talks did not start again until 2011. In the years between, the relationship between the UPF and KNO included other disagreements and pitfalls. It is unclear whether these two major organizations will cooperate in future talks.

Furthermore, the succession of operations agreement and framework agreement have not resulted in the groups’ disarmament, demobilization or reintegration nor has it stopped their collection of “taxes” from the local population. Indeed, it has not even meant the end of fighting between India’s Assam Rifles and insurgent groups under the agreement.

These mistakes and lack of policy learning on the part of India’s government suggest that the transformation of the Northeast through road connections with Southeast Asia are unlikely to materialize. Modi has built some feeder roads in the Northeast, but these stop short of the region’s mountainous areas. Despite new infrastructure, little has been resolved. What’s worse, these developments could give additional incentives to insurgent organizations to destabilize the region. In Moreh, the KNO and UPF are in an excellent position to push their demands through blockading any new highway projects connecting Manipur and Myanmar. It would be pure fantasy to expect otherwise. Opening of the border and accompanying new infrastructure mean nothing if New Delhi is unwilling to radically reevaluate its approach in Manipur. The first step will be to replace the practice of secret talks and empty promises with open and inclusive negotiations to foster collective solutions for all of Manipur’s diverse communities. Secondly, any feasible solution will have to include the devolution of power from the state capital, Imphal, to district capitals.

Brandon J. Miliate is the Librarian for South and Southeast Asian Studies at Yale University. He completed his PhD in Political Science at Indiana University in May 2019, during which he conducted nine months of ethnographic fieldwork in Northeast India and adjacent parts of Bangladesh and Myanmar. © 2019 YaleGlobal and the MacMillan Center