Shortly before 5pm on 22 February, a suited man with a lapel pin bearing the dimpled face of Kim Jong-un rang the doorbell of the North Korean embassy in Madrid. The man had visited the embassy before. Fifteen days earlier, he had been turned away by an official who was suspicious of his claims that he was a businessman hoping to invest in North Korea. Before he left, the visitor gave the official his card, which said he ran a Dubai-based investment fund named Baron Stone Capital.

Now the visitor had returned, claiming he had a gift for the embassy’s senior official, So Yun-sok. This time, he was ushered inside and asked to wait in the courtyard between the compound’s main two-storey building and its solid metal outer gate. While the official went to look for Mr So, the visitor walked to the perimeter of the compound and surreptitiously released the lock on the outside gate.

A few moments later, a group of men carrying combat knives, iron bars, handcuffs and fake pistols burst through the embassy door. According to a 14-page summary of the incident by the Spanish high court judge José de la Mata, within minutes all four male employees at the embassy had been tied up and bundled into a first-floor meeting room. The assailants, some wearing black balaclavas and others with their faces uncovered, spoke in American English and the distinctive Korean of Seoul and the South.

Mr So’s wife, named in Spanish court documents as Jang Ok Gyong, was watching television with their eight-year-old son when she heard what sounded like a struggle in the hallway. She locked the room, but soon the assailants forced their way in, though they insisted they would do her no harm. For the next four hours, she and her son were held captive, watched by a man with a black scarf over his face, a body camera and what seemed like a real gun in a holster. She claims she was so terrified that she secretly grabbed a razor to slit her wrists, but was unable to follow through. Instead, she and her son huddled together under a blanket.

In the meeting room, according to testimony from the embassy staff, the assailants placed black hoods over the hostages’ heads, swapped some of the plastic cable ties they had used to secure the hostages for handcuffs, and ordered them to sit in silence. One assailant was allegedly overheard asking another exactly how many people were taking part. “There are 11 of us,” was the reply. The senior official, So Yun-sok, was then taken down to the basement, where the group finally revealed one of its aims. They wanted him to defect.

Diplomatic defections are one of North Korea’s most visible problems, and in recent years there have been two high-profile cases. Just a few months before the embassy raid, in late 2018, the acting ambassador to Italy had abandoned his post and gone into hiding. Two years earlier, the deputy ambassador in London, Thae Yong-ho, became the most senior North Korean official to defect to South Korea.

In the basement, the attackers told So Yun-sok they wanted him “to become the ambassador of a new state set up by them – a ‘free’ state,” he later told Spanish investigators. The men claimed that “the North Korean government has very little time left” and said other groups were “going to do the same thing”. Yet there were no embassy raids in other countries, and Mr So refused to defect.

From this point onwards, the assailants’ plan began to fall apart. Eventually, with Spanish police outside the embassy growing increasingly suspicious, the men decided to make their getaway. They were remarkably successful. More than six months later, only one of the group allegedly involved in the raid has been detained – a 38-year-old former US marine sergeant, Christopher Ahn. A global manhunt is under way for up to 10 more assailants.

After the attackers fled, in the days and weeks that followed, details about their identities and aims started to trickle out, leaving as many questions as answers. The group seemed to be largely comprised of Korean Americans, South Koreans and North Korean defectors. But who were they? What did they want? Why did they fly across the world to attack an embassy in Europe? And what was the significance of the fact that one alleged member of the group turned out to have impressive connections within Washington?

Alongside the obvious strangeness of the raid itself, Korea-watchers were struck by the timing. A few days later, Donald Trump was due to meet Kim for a summit in Hanoi to discuss the denuclearisation of the Korean peninsula. Was that why this mysterious group raided the embassy? Spanish investigators remain puzzled, but Mario Esteban, a Korea expert at Madrid’s Elcano thinktank, believes it was an attempt to disrupt Trump’s meeting with Kim. “It was a very risky thing to do, in a friendly country, just before Hanoi – and messy,” he told me. “Nothing else makes sense.” That, however, is not what the attackers say.

Three days after the attack, an obscure dissident group called Free Joseon, or Free North Korea, claimed responsibility, and later announced they were forming a rebel government-in-exile. “We hereby take into our own hands our destiny and duty,” the group declared. Prior to the Madrid attack, only the most eager Korea-watchers had heard of this group, and observers are still piecing together clues about the group’s members and backers. “It’s a radical group of people you can call zealots, heroes or fanatics, depending on your point of view,” Andrei Lankov of Kookmin University, a leading expert on North Korea, told me by phone from Seoul.

There are two opposing versions of events inside the embassy, neither of them fully reliable. One comes from Free Joseon’s website, which strongly denies that violence was used. Its official line is that the group were responding to a request from embassy officials, who had contacted Free Joseon for help in defecting.

The second version comes from the hostages, who included the wives of two officials and an eight-year-old child. As servants of Kim’s murderous and paranoid regime, they must be careful not to upset their leader or his enforcers. Yet Spanish investigators found enough evidence in witness statements, police evidence and an embassy search to issue arrest warrants for “robbery with violence and intimidation”, “illegal restraint”, “threats”, “causing injuries” and membership of a criminal gang. The embassy officials described an experience similar to that of US army captives in Iraq, where Ahn’s battalion once ran a Fallujah detention centre. (Sources close to Ahn told me he was not the only military veteran involved in the raid, but refused to specify which country’s armed services the others had served in.)

The rights and wrongs of the case should eventually be decided at a trial in Madrid – that is, if the suspects can be located, the US agrees to Spain’s request for American suspects to be extradited, and North Korea allows its embassy staff to be cross-examined. In the meantime, court and police documents originating from Spain, Italy and the US point to three key, US-based players.

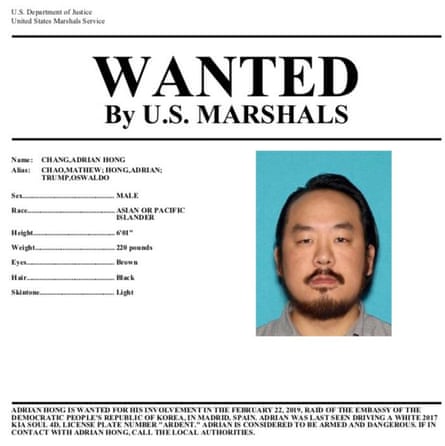

First, there is the group’s alleged leader: Adrian Hong. A wanted poster, released by US marshals, says Hong uses at least two aliases, is “considered to be armed and dangerous” and had been seen driving around Los Angeles in a large white Kia Soul SUV with a licence plate that read “Ardent”. It was Hong who posed as an investor when he first approached the embassy in early February. In reality, Hong is a Los Angeles-based, Yale-educated Mexican-Korean, with a long history of peaceful activism on issues relating to North Korea.

News of Hong’s alleged involvement in the raid astonished many who knew him. “You could have knocked me over with a gnat’s wing,” wrote Joshua Stanton, a Washington lawyer and author of the long-running Free Korea blog. Yet Spanish “government sources” told the newspaper El País that the country’s intelligence services had proof that Hong and at least one other group member had been in contact with the CIA. “They wouldn’t have said that if they weren’t sure,” claimed Esteban. (The state department has denied any US involvement.)

The apparent second-in-command was Samuel Ryu, a 28-year-old American who had allegedly been preparing the raid for months, but who remains a mystery. Then, there is Ahn, the former US marine sergeant, who was arrested in Los Angeles on 18 April and is fighting extradition to Spain. Ahn has not denied being present, but his lawyers claimed in court that the embassy takeover was peaceful.

Although the Madrid raid seems like a curious sideshow, it is worth recalling the stakes being played for in North Korea. These include nuclear warheads, chemical weapons, a brutal regime that murders and tortures, seven decades of armed standoff and tens of millions of Koreans potentially exposed to the deadly fallout should the Korean war ever start again. Many observers believe Trump is so keen to burnish his reputation by striking a historic deal with North Korea that he is making dangerous and foolish concessions to Pyongyang, without doing anything meaningful to reduce the nuclear threat that Kim’s regime poses. If Free Joseon’s aim really was to disrupt the Hanoi summit in February, they were not the only ones who were looking ahead to that meeting with concern. “People were afraid that Trump would basically sign everything to North Korea,” explains Lankov, who was in Washington at the time. “That was not just [a view held by] conspiracy theorists, but amongst very serious people.”

On a sweltering July afternoon in Madrid, I called the North Korean official, So Yun-sok, to ask him about the raid. “I won’t talk about that,” was his abrupt reply. In Spain, however, you do not need a diplomat to hear the Kim regime’s official version of events. Instead, you can turn to an eccentric Catalan aristocrat called Alejandro Cao de Benós.

Cao de Benós is, for all intents and purposes, head of global PR for North Korea, running an international network of cheerleaders for a country that sits at, or near, the bottom of most global lists for human rights. The 45-year-old Spaniard comes and goes from the Madrid embassy, vets and filters people wishing to visit the country, and ensures visas are issued for selected journalists, investors and tourists. In the past, he ran the Pyongyang Café, a North Korean-themed bar in his home city of Tarragona. For ceremonial occasions Cao de Benós dresses in a uniform festooned with medals, with gold lapel tabs and topped by a peaked officer’s cap with a red band. In conversation, he comes over as a cross between the enthusiastic promoter of an exotic tourist destination and a cold war-style critic of the “satanic” US. He denies that Pyongyang’s notorious regime tortures and executes dissidents. He is, in other words, an extremely unreliable source – but one with access to at least some inside information.

Cao de Benós forwarded me an email he received on 4 February from an “Elena Sánchez”, who claimed to be associate director of Baron Stone Capital. The investment fund had supposedly earmarked up to $50m to invest in “infrastructure, mining and energy” in North Korea, Mongolia and Myanmar. Its managing director was due in Madrid. Could he visit the embassy? “I started to vet them but the answer, for the moment, was ‘no’,” Cao de Benós told me. Baron Stone Capital does not appear to be a real company, and it has no presence at the Dubai address where it supposedly had an office.

It was three days after the email arrived that Adrian Hong first appeared at the embassy gate. He showed a fake Italian driving licence and, after being refused entry, left behind his Baron Stone business card. The following day, Hong flew from Spain to the Czech capital, Prague, but at least one of his alleged accomplices, Samuel Ryu, remained in Spain, staying at the Eurostars Zarzuela Park hotel, just 300 metres from the embassy. In June 2018, Ryu had lodged there for five nights with five South Koreans aged between 22 and 25, at least three of whom appear to have returned to participate in the embassy raid. It seems plausible that they made that trip to scope out their target.

Far from being the bunkered fortress that one might expect, the Madrid embassy is a low, beige and brown building, surrounded by rough land, with rickety- looking security cameras and the sort of low walls that a bored teenager might be tempted to jump. It is an easy, isolated target, sitting on an island of scrubby, undeveloped land in a remote corner of Madrid’s exclusive Moncloa-Aravaca neighbourhood. That, Lankov told me, might help explain why it was chosen for the raid. Apart from three embassy cars, a thief would have found little of value inside. North Korea is poor, and economic sanctions are hitting hard. The cash-strapped embassy housed just one diplomat, his family and three “administrative staff” (plus one staff member’s wife), who also did the gardening and acted as doormen. In sweltering Madrid, the embassy has a single air-conditioning unit that is wheeled out for visitors. The building’s insurance policy lapsed last year.

On 20 February 2019, two days before the raid, Hong returned to Madrid and renewed his passport at the Mexican embassy. By then, most of his team were already in the city and had begun buying equipment for the raid, making two visits to a large hardware store called Ferreteria Delicias. “It was odd because they were buying the sort of things you need for breaking into somewhere, but they were smart-looking and didn’t seem suspicious,” the store owner, Ramón Villar, told me. Among the items they bought were 10 iron crowbars, bolt cutters, a telescopic ladder, pliers and tape.

Hong, meanwhile, visited a self-styled “police boutique” called Shoke, which attracts self-defence hobbyists and Madrid cops wanting to stock up on everything from extra holsters and handcuffs to badges and boots. He bought four combat knives, five pairs of metal handcuffs, balaclavas, some quick-draw gun holsters and six authentic-looking pistols, which were actually harmless “airsoft” pellet guns. The bill came to €833.15.

It appears that one of the last to join the team was Ahn, who only arrived on a flight from New York at 8am on the morning of the embassy takeover. By midday on 22 February, with Trump due in Hanoi five days later, the team were ready.

If Free Joseon’s first mistake that afternoon was having no real Plan B in the event that So Yun-sok did not defect, their other major blunder was to leave an embassy resident unaccounted for. After the raid began, the wife of one of the administrative workers, named in court documents as Cho Sun Hi, locked herself in an upstairs room. She was terrified. In North Korea, South Koreans and, especially, Americans are painted as violent monsters. “I’d always been taught that it [the US] was the enemy, full of big-nosed, big-eyed, vicious people who’d killed my countrymen,” the defector Joseph Kim writes in his memoir Under the Same Sky.

Afraid of what the captors might do, Cho Sun Hi, who is 56, climbed on to a balcony and jumped into the garden, injuring her leg and cutting her head on a stone tile in the process. She then crawled across a paddle tennis court to a back gate, emerging bloodied and dirty on to the street. Seeing her in distress, a passing driver took her a few blocks away to the gates of a private clinic, though she spoke no Spanish and could not explain what was happening. Her wounds were tended to inside an ambulance that was called to the clinic. She only felt safe, she said later, after insisting they call the police. Through a translation app, she was able to explain to the police and ambulance crew that the embassy had been assaulted. It sounded absurd, but a patrol car was dispatched.

When police knocked on the door of the embassy, it was opened by a polite man in a suit, with a Kim Jong-un badge on his lapel. This was Hong. All was well, he told them. Police cannot enter a diplomatic delegation – which is inviolable and immune from search – without permission. Just in case, however, they waited nearby.

Inside the building, the assailants were beginning to panic. So Yun-sok had refused to defect, and now the police were outside. It was time to go. They took the keys to the three embassy cars and sped out of the compound, leaving behind only Hong and one accomplice. The cars were dumped in Madrid and the neighbouring town of Pozuelo de Alarcón over the ensuing hour, one with its doors open and the motor still running.

Back in the embassy, a few minutes earlier, Hong had ordered an Uber using the alias “Oswaldo Trump”. Now it was outside, parked in front of the embassy. But the police were there, too, and three North Korean students who had been trying to contact friends inside the embassy were preparing to jump over the garden wall to see what was going on. Instead of leaving in the Uber, Hong cancelled the ride and changed his plan. He and his accomplice went out the back way, through the overgrown plot behind the compound. A second Uber, again ordered by Oswaldo Trump, was waiting for him on a different street.

Just as Hong was escaping, the hostages were starting to free themselves. One rubbed his face on a sofa to lift the bag off his head, while Jang Ok Gyong found a knife to cut the remaining plastic cable ties. Within minutes, they spilled on to the street in front of the startled Spanish police officers. At least one man was still wearing handcuffs.

The raid had not exactly gone to plan, but it had not been a total failure. While the embassy staff were tied up, the assailants filmed themselves smashing portraits of the Kim family in a separate room. They later sent a video to Fox News. The symbolic potency of this is considerable, Sung-Yoon Lee, a Korea expert at The Fletcher School at Tufts University, told me. “It cracks the taboo that the Kim regime is inviolable and cannot be desecrated,” he says. They also stole So Yun-sok’s mobile phone as well as flash drives, and broke open computers to extract hard drives. All of the men involved managed to get away from the scene of the crime safely. The team fled to Lisbon, a six-hour drive away – with Spain’s ABC newspaper reporting that Hong took his Uber all the way, paying €900. On 23 February, accompanied by Ryu and two others, Hong flew from Lisbon to Newark, New Jersey.

Then, on 27 February, as Trump was meeting Kim in Hanoi, Hong made a puzzling decision: he contacted the FBI, explaining what he had done and handing over the stolen computer drives. Hong wasn’t detained at that point, since Spain had yet to issue arrest warrants. He was, however, admitting to having committed a serious felony in a friendly country, and when he met FBI agents again in mid-March, he also detailed Ahn’s role. This led to warrants being issued 10 days later and brought Ahn’s arrest (US marshals found him at Hong’s apartment), while Hong himself went on the run and has not been caught.

The question is why, after conceiving an elaborate plot, then bungling it, then evading capture, Hong would decide to admit it all to the authorities, only to then disappear again.

Adrian Hong arrived in the US in 1991 as a seven-year-old boy. His father Joseph was a taekwondo champion and Christian missionary who had emigrated from South Korea to Tijuana, Mexico – where Hong was born, and his father taught martial arts under the nickname “El Tigre” – before moving a dozen miles across the border to Chula Vista, San Diego. The family eventually settled into a suburban house backing on to a busy freeway.

Hong inherited his father’s missionary zeal. As a 17-year-old Yale freshman, he wrote to the Korea Herald, an English-language newspaper in Seoul, to berate young Koreans and Korean-Americans for lacking “passion for their nation” while sporting the “horrible-looking haircuts and clothes styles” inspired by early K-pop. He described himself as a proud Korean patriot who was “ashamed” of his people for their political apathy and loose morals.

Determination, charisma and righteous conviction took Hong a long way. In 2004, he helped to host the annual Korean American Students Conference in New Haven, where he co-founded an organisation called Liberation for North Korea, or Link. Link, which later changed its name to Liberty in North Korea, was spectacularly successful. Some four years later, aged just 22, Hong was running an NGO with 100 campus chapters worldwide, an annual income of $143,000 and funding from Washington’s Freedom House thinktank.

Link’s co-founder was Paul Kim, a Korean-American comedian known as PK. In April, a couple of months after the embassy raid, Kim received a visit from US marshals on the hunt for Hong, though he didn’t know his old friend’s whereabouts. “He’s not the bad guy here. He’s one of the smartest guys I know, and also one of the most eloquent writers,” Kim told me on the phone from Los Angeles. Kim also recalled that Hong’s strident activism sometimes failed to impress native Koreans. When American members of Hong’s organisation set up mock funerals in Seoul to highlight the plight of North Korea’s citizens, many locals took offence. “People were like: ‘You don’t live here, you don’t understand. Don’t tell us what to do’,” said Kim.

Hong’s grand passion was helping refugees from North Korea. Any North Korean who manages to escape across the border to China faces a difficult path. If Chinese police catch them, they are sent back home, where they risk instant punishment. Most who manage to evade capture are forced to live clandestinely, often in poverty, or end up falling victim to people-traffickers. Link became one of several groups running “underground railroads”, helping defectors make their way to South Korea or beyond. These still operate today, and Link has rescued more than 1,000 people over the past decade.

Hong would sometimes travel to China to assist with Link’s work, displaying the bravery and apparent calmness under pressure that he would later show in Madrid. In some cases, he accompanied young escapees through China personally, buying them fashionable clothes and teaching them to pass as spoiled Korean Americans so that they could travel more freely. “He was young, his hair was cut in a stylish way, and his clothes were American and very hip. Everything about him, in fact, was cool,” wrote Joseph Kim in Under the Same Sky, after Hong calmly walked him into a US consulate in China. But, just like in Madrid, Hong also had a tendency to overreach and to place exaggerated faith in his own abilities, with disastrous consequences.

In December 2006, Hong attempted to force the US consulate in Shenyang, a city in north-eastern China, to admit six North Korean refugees. The plan misfired. His team and the refugees were all arrested, though Hong’s eight days in jail were minor compared to the months of prison suffered by others who have been caught helping refugees over the past decade.

Tim Peters of Helping Hands Korea, a Christian NGO, told me that Hong’s rashness in Shenyang had alarmed those who had spent years quietly building escape networks. “It really sent shock tremors through the whole community,” he said. Although the Shenyang Six were allowed to leave the country eight months later, extra Chinese guards were placed around consulates, making it “less likely than ever” that escapees could seek asylum in the US, noted the journalist Melanie Kirkpatrick in her book Escape from North Korea.

After Madrid, Peters worries people will conflate the underground railroad with violent attacks such as the embassy raid. “That’s political,” he said. “It’s not what we, or others, do.” Link has also distanced itself from Hong, pointing out that it has been more than a decade since he was involved with the group. However, sources at Spain’s National Court confirmed to me that it has also issued a warrant for Cheol (or Charles) Ryu, a 25-year-old US citizen who fled North Korea as a teenager, posts on Instagram as @freshprinceofpyongyang (bio: “just chillin’ in USA until I can go back to the Hermit Kingdom”) and worked with Link until late last year. “It appears that he was contacted by Adrian Hong and, unbeknownst to our organisation, recruited to be involved in Free Joseon’s activities after leaving Link,” the group’s CEO, Hannah Song, said in a statement sent to me by Link. Ryu has not responded to my emails or Facebook messages. A fifth warrant has been issued in the name of South Korean Woo Ran Lee, the same sources said.

In 2008, back when Hong decided to leave Link to devote himself to political advocacy, he wrote a farewell note. “Liberty will come for the North Koreans soon,” he promised. From that time onwards, his movements become harder to piece together. What is certain is that he built contacts in Washington, thinktanks and academia, becoming accepted as a serious advocate for change in Korea. He was involved in several social start-ups and became a TED Fellow in 2009, networking and creating independent conferences about political change in Asia and Africa. In 2011, after Libya’s leader Muammar Gaddafi was deposed, Hong organised a conference in the Rixos Hotel in Tripoli, hailing the Arab spring as “a dress rehearsal for North Korea”. Yet the Kim regime stayed stubbornly in place.

In Washington and elsewhere, Hong won admirers. He had strong enough connections to secure five visits to the White House between 2011 and 2012, and has photographs with Barack Obama to prove it. “He is a very suave, charming personality in any social setting – self-confident, but not arrogant,” said Lee, who invited him to talks to his students at Tufts in 2013 after Hong had set up an NGO consultancy called Pegasus Strategies. How Hong made money during this time remains an unresolved question, though South Korea’s conservative Chosun Ilbo newspaper has claimed, without offering evidence, that “his consulting work often involved the CIA”. Whatever the case, in retrospect it seems that Hong’s impatience for change was growing.

In 2015, Hong created the Joseon Institute. Its mission statement predicted “seismic shifts in the near term” and spoke of preparing administrators for a free North Korea. It boasted British Conservative MP Fiona Bruce as one of three advisers – the others were former prime ministers of Mongolia and Libya – and claimed to operate in New York, London and Shanghai. (Like many who have worked with Hong, Bruce declined to comment.)

The institute never lived up to the hype, organising only a tiny number of events. It did boost Hong’s profile, though, and in March 2016, he was invited to speak to the Canadian senate’s standing committee on human rights. That day he was in messianic mode, stating that dialogue with Pyongyang on human rights was pointless. “They’ve tortured themselves into a corner,” he argued, while continuing to insist that North Korea was “on the cusp of the change”.

It is not clear when Hong first met his alleged future accomplice Ahn, but Ahn’s early life, growing up in LA’s large Korean community, was also rooted in church and family. Like Hong, Ahn had been a serious teenager. He once phoned a local radio station to lament Americans’ “lack of patriotism”. At 19, Ahn joined the marines and went on to serve for six years. “As a Korean-American, I really treasured the soldiers and marines who lost their lives to liberate Korea,” he told the Washington Times for a 2008 article about Vets for Freedom, a Republican-aligned advocacy group. “I always viewed my service as kind of paying it forward.” Colleagues claim that Ahn later ran up a large personal debt to help both Vets for Freedom and out-of-luck veterans.

By early 2017, Ahn and Hong were undoubtedly in contact, since the two were about to undertake an extraordinary secret mission in response to an event that made headlines around the world. On 13 February 2017, Kim Jong-un’s exiled half-brother, Kim Jong-nam, was murdered at Kuala Lumpur airport when assassins tricked two women into squirting him with VX nerve agent for a fake TV prank. In the immediate aftermath of this assassination, there was reason to believe that the rest of Kim Jong-nam’s family were in grave danger. But the family were quickly spirited away to safety from their home in Macau.

The following month, a 40-second video appeared on YouTube, featuring Kim Jong-nam’s son, Han-sol. “My father has been killed a few days ago. I am currently with my mother and sister,” said Han-sol in English. He continued, “We’re very grateful to – ”, before the sound on the video cut out, preserving the anonymity of the people who helped him to safety. The video was posted by a previously unknown group named Cheollima Civil Defense, which also published a statement on their website thanking the governments of the Netherlands, China, the US and one unnamed nation for their assistance in rescuing Han-sol and his family. Cheollima Civil Defense later renamed itself Free Joseon.

After the Madrid attack, with Spanish authorities having broken Hong’s cover, Free Joseon released the unredacted version of Han-sol’s video, in which he thanks “Adrian and his team” for their help. According to Free Joseon’s website, Hong was assisted by Ahn, who “personally protected and escorted Kim Han Sol and his family”. It was only then, two years after the incident, that the identity of the people behind Han-sol and his family’s escape from danger was revealed. “I was impressed they managed to maintain secrecy for so long. That shows great discipline,” says Lee, who was “stunned” to see Hong revealed as the man behind the rescue mission.

A separate website, Freedom for Free Joseon, set up this summer to defend Hong and Ahn, makes some extravagant claims about their importance. “These men, as part of the provisional government of Free Joseon, represent the first legitimate threat to Pyongyang in decades,” it claims. Earlier this year, Hong’s organisation also began selling advanced 45-day visitor visas “to visit Free Joseon (previously North Korea) upon liberation”. These must be paid with cryptocurrency and cost one Ethereum, currently worth around $225.

Hong has done remarkable things in the past, but analysts say his government-in-exile is more fantasy than reality. Speaking about the embassy raid, Jean H Lee, a former AP news agency bureau chief in Pyongyang who now works at the Wilson Center thinktank, told me that she believes “these actions have jeopardised lives on all sides: their own, those of defectors they have extracted, and those in the embassy”.

The Free Joseon website provides a contact email address, but messages I sent over several weeks remain unanswered. There is, however, at least one public figure willing to defend the group.

Lee Wolosky is a deeply connected Washington insider who held antiterrorism roles under presidents George W Bush and Bill Clinton, served as Barack Obama’s special envoy for Guantánamo closure, and has now taken on a new role, as Hong’s lawyer. Wolosky has appeared on Fox and CNN to discuss Hong’s case. “We are dismayed that the US Department of Justice has decided to execute warrants against US persons that derive from criminal complaints filed by the North Korean regime,” Wolosky said in a statement posted on the Free Joseon website. (Wolosky confirmed to me that the statement was genuine, but declined to talk further.)

A source close to Wolosky told me he was working pro bono, at the request of “a friend” outside government who is not associated with Korea. His involvement, nevertheless, raises questions about who is backing Hong’s buccaneering “liberators”. Foreign dissident groups such as Free Joseon are quick to exploit the factionalism of Washington, and few issues offer as many opportunities as Trump’s flirtation with Kim. Hong has occasionally moved in similar circles to John Bolton, the ultra-hawkish US national security adviser, who has previously called for a pre-emptive strike on North Korea and who, some observers believe, wants to undermine Trump’s attempts to reach a nuclear agreement with Pyongyang. Wolosky is also a lawyer for United Against Nuclear Iran, a group co-founded by Bolton that describes Kim and the ayatollahs as “nuclear proliferation partners”. Free Joseon says it also wants to prevent weapons sales to Iran. (The CIA has denied any role in the affair, and there is no evidence to suggest any direct connection between Bolton and Free Joseon.)

The failure of the Hanoi summit and recent tit-for-tat military exercises and missile launches have not erased the fear among North Korea hawks that Trump might do a deal favourable to Kim’s regime. Lankov agrees that Kim will never give up nuclear arms, but says Free Joseon’s dreams of an Arab spring-style uprising are also fantasy. “If they have a rebellion, they will just machine-gun protesters,” he told me.

Nor will North Korea’s elites allow Kim to renounce nuclear arms, since these guarantee their own long-term power and safety. Yet those same elites expect Kim to deliver relief from sanctions. Trump, meanwhile, is thinking about re-election in 2020. “Bolton has been pushed aside. Donald Trump just wants something to show voters,” Lankov told me after another trip to Washington in July. He foresees an imperfect, partial deal that will eventually fall apart, but with a triumphant Trump crowing that he has “solved the north Korean nuclear problem”. As China grows, however, the influence of Trump or his successors compared to Xi Jinping and future Chinese leaders will wane considerably. “The US’s window of opportunity for shaping the future of an Asia-Pacific nuclear player is closing,” Robert Kelly of Pusan National University told me.

In the meantime, will the men behind Free Joseon get away with their audacious actions? In a remarkable twist, Ahn was released on $1.3m bail in July, despite the fact that almost all US citizens sought on international arrest warrants from Europe are routinely held in custody. The court decision, which allows Ahn to wear a tracking device and live at home in LA while awaiting a full extradition hearing early next year was, in the words of his lawyer Naeun Rim, “very rare”. Rim argues that Spain’s warrant is based on unreliable evidence from servants of Kim’s regime, and the judge accepted FBI evidence that Ahn was at risk from North Korean assassins. “It’s a life or death situation for him,” Rim told me. She is likely to present similar arguments at Ahn’s full extradition hearing next year, when the bar for avoiding being sent to Spain will be much higher. Minimum sentences there for both illegal detention and belonging to a criminal organisation are four years.

Despite Free Joseon’s apparent amateurishness and self-glorification, the group has highlighted a key political problem by styling itself as a “provisional government” for North Korea. This fits Korean history, with a government-in-exile first challenging Japanese colonial rule early in the 20th century. Yet it also defies expectations of an eventual reunification of the two Koreas. In fact, joining the poor North to the wealthy South is so fraught with cultural and other complications that it makes Germany’s tortured reunification seem simple. Many in the South already fret about the immense cost, while their government continues to run a ministry of unification. “If the North Koreans can just hang on another generation or so they won’t need to worry about unification, because the two Koreas are growing so far apart,” argues Kelly.

The Madrid raid may eventually become an anecdote in the tragic story of Korea under the Kims. If it was an attempt to stymie Trump’s talks, it failed. “We fell in love … No really, he wrote me beautiful letters,” Trump insisted when he and Kim began their flirtation a year ago. On 6 September, Trump’s secretary of state, Mike Pompeo, told Kansas radio station KCMO that the love affair would be back on soon. If Kim gave up nuclear weapons, he suggested, he could do anything else he wanted. “Every nation has the sovereign right to defend itself,” Pompeo said. Kim is famous for finding creative ways of doing that. Stories of enemies being liquidated with flamethrowers, anti-tank guns or even piranha fish may prove to be exaggerations, but he was happy to kill his brother with a nerve agent. Millions of North Koreans, meanwhile, continue to struggle with abject poverty and repression. Freeing Joseon, surely, means getting rid of more than just its nuclear weapons.

This article was amended on 11 September 2019 because an earlier version said that a diplomatic delegation was “sovereign foreign territory”. Under the Vienna Convention, while a foreign embassy building is inviolable and immune to search, it is not formally “sovereign territory” of the embassy’s country.