Tanzania ‘natural treasure’ draws crowds far from home

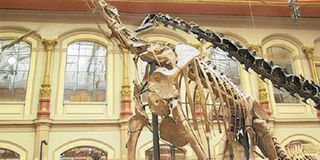

Berlin. After taking a few steps into the Naturkunde Museum in Berlin, the first artefact you will see is a skeleton of the uniquely tall dinosaur, the Brachiosaurus brancai (Giraffatitan).

Standing at 13.27 metres high, the Giraffatitan is the tallest mounted dinosaur skeleton in the world, as the Guinness (Book of) World Records affirms. Hence the ‘moniker’ Giraffatitan, meaning a titanic giraffe, genus of the sauropod dinosaur that lived during the late Jurassic Period: the Kimmeridgian-Tithonian stages.

The beast was originally named as an African species of Brachiosaurus (Brachiosaurus brancai), but this has since been changed.

“Visitors have nicknamed it ‘Oskar,’” said the director general of the Prof Johannes Christian Vogel during an interview with a group of journalists from Tanzania and Kenya who visited the facility in early September.

In Germany, the name ‘Oskar’ refers to a ‘God spear,’ ‘deer-lover’ or ‘champion warrior.’

Standing tall in the centre of the hall of the museum, dinosaur Oskar is the symbol of Naturkunde – and, regardless of the presence of other artefacts in the place – its uniqueness attracts visitors from all over the world.

According to Prof Vogel – a German botanist and Professor of Biodiversity and Public Science at Humboldt who, since February 1, 2012, has been director general of the Naturkunde Museum – the museum holds a collection of about 30 million specimens for research. Some of them – including the Giraffatitan dinosaur – are exhibited for the public to admire and wonder at.

“The museum’s exhibitions are seen by more than 700,000 visitors per year,” said Prof Vogel.

One interesting fact about ‘Oskar the Giraffatitan’ is that it was one of the skeletons that were brought here from the expeditions that were made to Tendaguru Hills in what is today the Lindi Region in south-eastern Tanzania.

This was between 1909 and 1913 when the country was under German rule as Deutsch Ostafrika (Germany East Africa).

Scientists of the museum, led by palaeontologist Warner Janensch (1878-1969), found approximately 5,000 artefacts with a combined weight of around 250 tonnes, which they shipped to Germany.

Apart from Oskar the dinosaur, the German expeditionists also retrieved the remains of the Janenschia Robusta, which belonged to a family of the largest dinosaurs that ever lived; but it’s still a smaller creature compared to the Giraffatitan.

Today, not that many Tanzanians out of the 55 million-strong population have knowledge of the existence of this relatively unique collection which has been on show at the German museum for over 80 years now.

Missing experience

Inside the museum, the special collection is displayed in a thoroughly secured environment to preserve the fossils, as well as enable visitors and scientists to view – and even study them.

Scientists are able to study the bones and develop new findings from time to time. If nothing else, this helps in developing education especially in the field of natural history, focusing on biodiversity, evolution and earth sciences.

In terms of tourism, the museum has installed interactive telescopes – called ‘Jurascopes’ – that show visitors animation of how the original skeletons in the exhibition turn into ‘live animals.’ This is really most exciting!

But, it is also painful to realise that there is a generation of Tanzanians who are not able to finance a trip to Germany and, as such, will never have the opportunity to personally experience the unique artefacts that originate in their motherland, and which are now the cynosure of world-class tourists in a foreign land.

Retention debate

A number of Members of the Union Parliament recently appealed to the Tanzania government to prevail upon Germany to return the fossils to their country of origin so that Tanzanians could benefit from them through tourism earnings.

There are reports that the two governments did dialogue on the return of the unique treasures. But we were later told that the Tanzania government ‘argued that there were no proper logistics that would accommodate the preservation and display of these artefacts – let alone doing so for tourism purposes!

Taking into serious consideration the amount of money that the German federal government has been spending on scientific researches and preservation of these precious, rare collections, it can reasonable be argued that the Tanzanian government does indeed have a valid point.

On the issue of whom the dinosaur belongs to, the Naturkunde Museum chief said it can just as well be said that Girraffetitan belongs to everybody – if only because, according to history, humans and dinosaurs have never co-existed in mutual harmony.

Even during the time when the remains were taken to Germany, there were no country’s boundaries-defined nation-states, only colonies.

“But, I really have no say on how this might be decided. As a director (of the Museum), my job is only to take care of these historic collections. It is really a political matter – and the German state will do that on my behalf,” Prof Vogel waxed lyrical.

Very expensive to keep

“Costly...” This is one word that the director of the museum, Prof Vogel, can use to describe how much it has already cost the museum – which is basically under the German Federal State Government – in terms of the dinosaur collection’s upkeep.

Starting from the initial point of research process, a lot of money must have gone into the whole undertaking.

“If you look at what it costs to produce a scientific paper in the West… Well, it is roughly equivalent to a million euros. Add to that the fact that one dinosaur’s collection has had about 200 scientific papers written about it in the past 100 years,” Prof Vogel elaborated.

This means that, in terms of the investments done in the science only, nearly €200 million have been used. When computed using the current exchange rate, it amounts to more than Sh507 billion!

The Naturkunde facility also comprises a variety of general and high-end laboratories, a large scientific library, more than 70 professional scientific staff and an upgraded ICT infrastructure installed with the goal of digitizing their work.

Being a research museum, Naturkunde (roughly German for ‘Natural History,’ or ‘Nature Study’) is devoted to basic research and education in all fields of natural history, focusing on biodiversity, evolution and earth sciences.

Holding such a large collection of artefacts – about 30 million, ye gods! – the Naturkunde Museum is like a huge charity institution, as there are more costs to managing it than profits, Prof Vogel said, somewhat philosophically.

“You cannot make any profit out of it; it instead costs you so much,” he stressed – revealing that huge investments continue to be made in it in order to operate it successfully as a public museum. This is especially when you take into account the science aspect to it.

Ready to support

“There are a lot of exciting discoveries that are yet to be made in this piece of land on Planet Earth called ‘Tanzania,’ and we will be happy to do it with you (Tanzanians) – if you are really interested,” Prof Vogel rhapsodised.

In that regard, he revealed that a team of scientists who made an expedition to Tanzania early this year discovered fragments of dinosaurs near the area where the first excavation took place in early last century.

“We are willing, able and ready to support and build capacity for any scientific research and related development that the country (Tanzania) would want to make,” the good professor pledged – adding that his Museum has been conducting researches in Tanzania, doing so in partnership with such institutions as the University of Dar es Salaam.