- India

- International

Looking for Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi 150th Birth Anniversary: On the 150th birth anniversary year of the Mahatma, a journey from Ahmedabad to Delhi to trace the Bapu who survives in the memories and aspirations of contemporary India.

Godhra is too storied to bypass as one leaves Gandhi’s home state Gujarat. There is more to the city than 2002 and the S6 coach. (Illustration: Suvajit Dey; designed by Gargi Singh)

Godhra is too storied to bypass as one leaves Gandhi’s home state Gujarat. There is more to the city than 2002 and the S6 coach. (Illustration: Suvajit Dey; designed by Gargi Singh)

Ahmedabad

DAY ONE: September 21, Saturday, 11:00 am

You don’t expect to hear about Gandhi’s planned “surgical strike” of sorts on Pakistan at the start of the journey to rediscover the Mahatma. That, too, just 100 m from his first base camp on his return from South Africa — the much-neglected, 1915-dated Kochrab Ashram in Ahmedabad. Maybe, it was the question.

Asked about Gandhi’s relevance 150 years after his birth, historian Rizwan Kadri, 50, fishes out a thick wad of neatly photocopied spiralbound papers. It has evidence to suggest that Bapu, like most contemporary leaders on both sides of the divide, also spoke of war, or, at least, gave it a thought; maybe even joked about it.

ALSO READ | The deep ties between Gandhi and the American civil rights movement

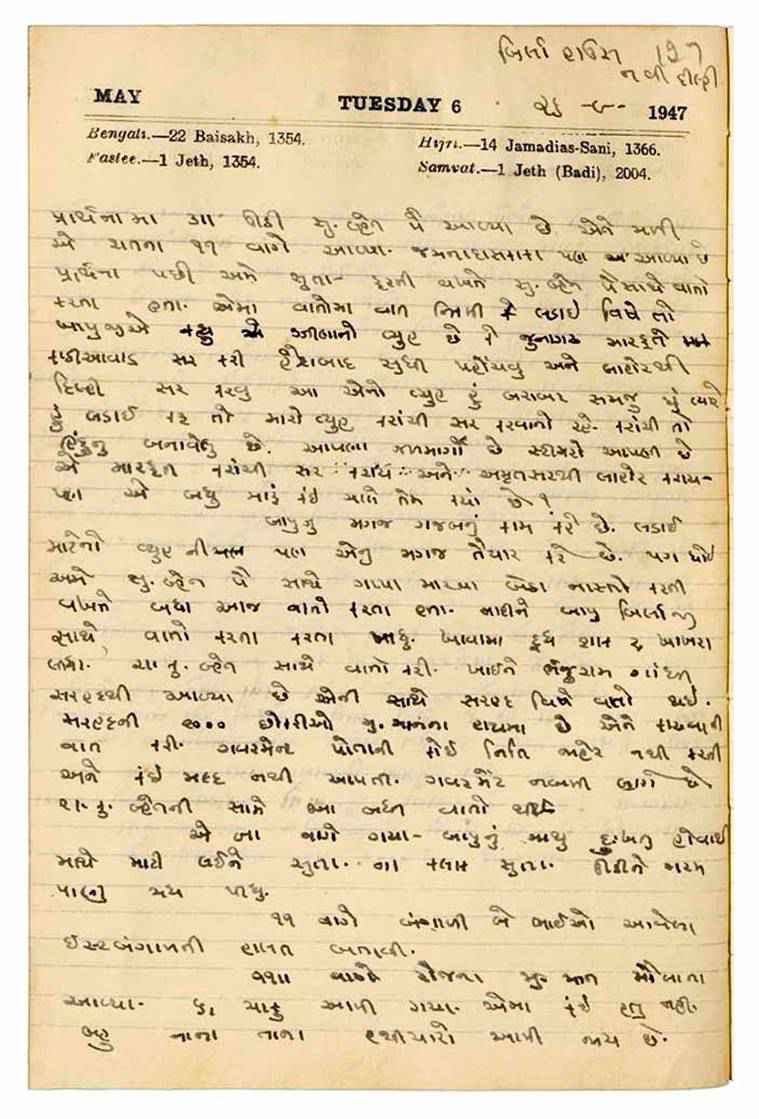

These are pages from Manuben’s diary — the diligent notes by the girl who was Gandhi’s famous shadow — and, on whose lap he would breathe his last after being shot. Kadri points to an entry from September 26, 1947. That’s more than a month after Independence and the bitter Partition. Those were testy times of mistrust when, as we know now, even the most non-violent seemed to be flirting with fire.

Manuben is conversational in her writings; it’s mostly in colloquial Gujarati. She is narrating one particular evening of “guppa” session over khakhra and doodh that Gandhi had with his guests to a friend. “During the chat, the topic of war came up. Bapu said that (Muhammad Ali) Jinnah was thinking that by conquering Junagadh he could rule Kathiawad and even reach up to Hyderabad. And conquer Delhi from Lahore”.

Then she mentions Gandhi’s rare un-ahimsa utterance, highlighted by Rizwan’s flaming green marker. “I understand Jinnah’s view. If I fight, my view is to conquer Karachi. It is built by Hindus. We have our waterways, we have our steamers, with them we can conquer Karachi and also conquer Lahore via Amritsar.” This is followed by a pithy line: “Pun aa baadhu maaru kyan chaale tem kyan chee (loosely translated as “But when it comes to all these, I don’t have a say).”

A page from Manuben’s diary.

A page from Manuben’s diary.

Gandhi’s realisation of his sudden marginalisation is followed by Manuben’s expression of unwavering awe towards her larger-than-life mentor. “Bapu nu magaj gajab kaam kare chhe (Bapu’s mind works wonderfully. He is even ready with his views on war).”

Many sections of Manuben’s diary are like an accountant’s daily log — cut and dry. Intriguing emotions and episodes are hidden among entries of mundane chores and the drudgery of everyday life. Her matter-of-fact full stops at the end of pregnant sentences add an air of mystery to those times and that “gajab magaj”.

ALSO READ | Bapu’s Life, His Message

Kadri, too, fancies himself as a dispassionate chronicler, an “investigative” historian. “I never say anything without proof,” he keeps repeating. Kadri didn’t need to learn about the freedom struggle from his school’s SST books. His forefathers were Gandhi’s neighbours — they knew Bapu much before he became the Mahatma. Discussions about Gandhi and the freedom struggle took place in his courtyard — there was also this one time when his family members stood in their porch to see off the salt satyagrahis. History had a habit of taking the narrow road outside Kadri’s present home, a Gandhi heritage site.

Of late, the history professor with a college managed by the Swaminarayan sect, had been involved in the Statue of Unity project. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel is another of Kadri’s favourite topics. He mentions Jawaharlal Nehru but in the context of Patel unfairly missing the post of Congress president and the prime ministership. Ask him if Gandhi deserved to have the tallest statue and he gives a long answer that’s short on clarity. He wants to talk about Manuben’s diary and Gandhi’s words on war, the narrative that suits the present times.

Just like the curio seller at the Khadi Bhawan shop near Sabarmati Ashram.

Sabarmati Ashram (3 pm)

The one who changed the world: The Sabarmati Ashram on a lonely afternoon (Photo: Javed Raja)

The one who changed the world: The Sabarmati Ashram on a lonely afternoon (Photo: Javed Raja)

“Everybody is buying these,” says the young salesboy pointing to the neatly-arranged wooden pen stand that spins on its axis. They are placed at a strategic corner of his table to catch most eyes. Cuboid in shape, it has pictures of leaders on all four sides. Gandhi, Patel, (Subhas Chandra) Bose and, yes, Modi.

“They are all freedom fighters,” shouts the eager seller. He knows you have spotted the “odd one”. “Arre, woh bhi freedom fighter hi hai,” he says. To offer variety, he picks another one. This one has Gandhi, Patel, Modi and, yes, Bhagat Singh.

Inside the Ashram, the weekend hasn’t attracted many faithfuls, or even the tourists from Bengal. It’s late afternoon, the Ashram’s airy, open verandahs with black-and-white pictures on the walls are occupied by students from nearby colleges. They seem to be regulars, they seem at home. Books, cell phones, colourful backpacks, dupattas and helmets are littered around them. It’s like a messy teenagers’ room.

A couple of girls and boys are preparing for competitive exams. “Do you know what was Kasturba’s maiden name?” asks the studious kind. Silence. “Kapadia,” says the quiz master. Lame wisecracks featuring Dimple Kapadia and Twinkle Kapadia follow. The less studious, more-in-love young couples aren’t indoors. They are staring at the silent Sabarmati that flows behind the Ashram.

Among the roadside hawkers, there is talk about the soon-to-be-announced Ashram makeover. They are expecting to be driven out, like it was done around the Statue of Unity. Has the number of tourists here reduced after Sardar’s Guinness Book entry? “No, it has increased, tourists come here after going there,” says a worried looking man selling miniature charkhas. Gandhi piggybacking on Patel? What a comeback Sardar has had around here.

ALSO READ | Leo Tolstoy to Dada Abdulla, the international influences on the Mahatma

A neatly formed train of pre-school tots and their harried teachers finally bring life to the place. Their yellow T-shirts says Genius Generation. They look knackered, thirsty and slightly cranky. The struggling teachers come up with a masterstroke. Using Gandhi’s three monkeys on the lawns as props, they begin an impromptu photo session. The older sari-clad teacher makes the children, in batches of three, pose like the monkeys behind them. The younger teacher, in jeans, turns photographer for the session, with her phone camera. The frame of kids with hands on their eyes, ears and mouth is probably the most inspiring moment on that muggy lazy Saturday afternoon at Gandhi Ashram.

Just a year after the Sabarmati Ashram came up in 1917, Gandhi was moved by the plight of farmers in Kheda. (Photo: Javed Raja)

Just a year after the Sabarmati Ashram came up in 1917, Gandhi was moved by the plight of farmers in Kheda. (Photo: Javed Raja)

Kheda

Day one: September 21, Saturday (5 pm)

Just a year after the Sabarmati Ashram came up in 1917, Gandhi was moved by the plight of farmers in Kheda. Like bank Shylocks of modern times, the British government was infamously insensitive to crop failure when it came to collecting taxes.

Gandhi travelled 50 km to Kheda to be with the leaderless peasants. We, too, follow history and reach the village of about 16,000.

Kheda’s famous hard-fought win is forgotten now. Ask anyone about the Satyagraha and you get a blank stare. As a desperate measure, you get into the police station to report the satyagraha that has gone missing. One young cop, Rohit, says he has heard about it but gets the year wrong. Quiz him on what Gandhi means to him, and he blurts out “satya aur ahimsa”. The seasoned pros, the seniors — sitting among weapons, sticks and handcuffs — let out a laugh. Rohit joins in. The scared-as-a-trapped-mouse puny man behind the bars in the corridor is the only one in the vicinity who wouldn’t have found the joke funny.

Rohit has a solution — he gives us the number of a local reporter, who in turn directs me to Kheda’s most informed citizen — 75-year-old Vishu Prasad Vyas.

He is helpful, selfless, assertive and indomitable. If you are in trouble, you would want Vyas on your side; he would get everyone’s vote if he ran for any RWA elections. The one-time accounts officer in Gujarat Electricity Board and a formidable union leader, the man, now hard of hearing, has all the details of the 1918 farmers’ protest. He takes you to the derelict and deserted former court where Gandhi and Patel had appeared. Sadly, he says, years later during the Gujarat’s Navnirman Movement of the mid ’70s, the three-floored imposing structure was burnt down by protesting students. Vyas says he was always for Gandhi’s method of non-violent protest. “It is more effective,” he says.

The fire inside him is still burning but the coldness of the young towards public causes makes him disillusioned at times. “But I don’t care. I still raise my voice against what’s unfair. Unlike in Gandhi’s era, today you can’t mobilise a mass protest regardless of the scale of injustice,” he says.

Vishu Prasad Vyas in Kheda, where Gandhi had once joined a farmers’ protest. (Proto: Javed Raja)

Vishu Prasad Vyas in Kheda, where Gandhi had once joined a farmers’ protest. (Proto: Javed Raja)

His latest peeve is the toll booth on a section of the highway that joins Ahmedabad and Dandi. It happens to be on the tourist-friendly section that the state government wants the world to travel to and get a feel of Gandhi’s Salt March. Vyas is outraged.

“Imagine, you pay tax on the same road that Gandhiji walked to avoid taxes back in the day. Imagine, if a foreign tourist passes this toll, what impression he will carry home. Imagine, how hypocritical we have become,” says the man who has written letters and got memorandums signed by Kheda residents and passed them to MPs, MLAs and collectors. “But I won’t stop,” he says, embodying the spirit of the man who once listened to and stood for Kheda’s unheard.

Godhra

Day 2: September 22, Sunday (1 pm)

Godhra is too storied to bypass as one leaves Gandhi’s home state Gujarat. There is more to the city than 2002 and the S6 coach. Beyond the railway platform, the city of “50-50” Hindu-Muslim population of 1.5 lakh is a bundle of contradictions.

Dividing the city into two halves — West for Muslim, East for Hindus — is Road No.2. Many from the west have relatives in Pakistan. Several from the east have migrated from Pakistan, mainly Sindh. It’s a strange mix. Just last month, about 80 people from the west were stranded in Pakistan because of the blockade on the border after the abrogation of Article 370 in Kashmir. It was the intervention of a journalist from the east that brought them back home.

Though the city has a history of communal tensions, the locals feel Godhra 2002 got them undeserving infamy. Sitting at Gandhi chowk, Aslambhai says Godhra didn’t see a single killing in the city after the train got burnt. His friend Karsanbhai nods. They also talk about the many joint businesses owned by residents of the east and west.

Urban legend, make it rural, has it that it was in Godhra that Patel, a Gandhi sceptic once, became a Bapu believer after listening to his lecture. Gandhi’s simple idea of nationalism — inclusiveness and tolerance to divergent views — finds an echo here, especially at the Kesari Chowk deep inside west Godhra.

Farukh Kesri is a busy man. He buys motorcycles confiscated by loan sharks and resells them. The middle-aged man in white, with a skull cap, has another important responsibility. Every day, after dawn and before dusk, he has flag duty.

At Kesri chowk, the crowded square near his shop, there’s a tricolour which never fails to come up each morning and go down in the evening. “After 2002, I was requested by the local police to do this and also to celebrate August 15 and January 26. Now, these have become highly anticipated events. I spend close to Rs 1 lakh,” says Kesri as he fiddles with his computer mouse to look for videos. Soon, there are scenes of a festive Kesri chowk, crowded with locals waving national flags and kids with tricolour painted faces on the screen. There’s also one of him distributing biscuits and water to the Ganesh visarjan procession that passes through the narrow lanes of West Godhra.

What do you feel when people are asked to go to Pakistan for dissent or even for diversity? “I don’t watch news channels,” is his short answer.

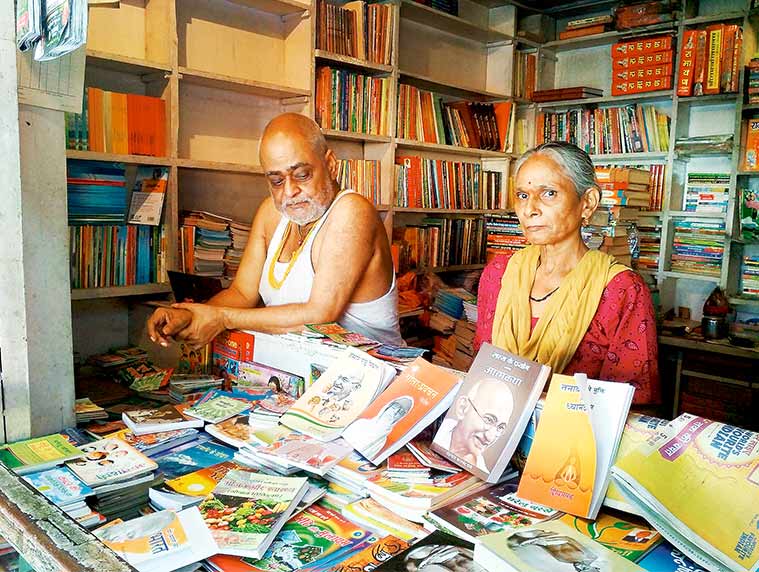

Bapu’s Army: Gopal Krishan Sharma and his wife Anu in their bookshop in Ratlam. (Photo: Sandeep Dwivedi)

Bapu’s Army: Gopal Krishan Sharma and his wife Anu in their bookshop in Ratlam. (Photo: Sandeep Dwivedi)

Ratlam

Day 3: September 23, Monday (8.30 am)

Platform No 4 of the very busy Ratlam railway station gets the majority of the over 80 trains that stop by at this central Indian city on the Mumbai-Delhi route. All through the day, like a sea during high tide, manic human waves hit this port, triggering a mad frenzy all around. But for the tiny Sarvodaya bookshop which isn’t dictated by the pace of the place or time.

Gopal Krishan Sharma, 62, has been manning this post since 1993. He is proud of his collection of Hindi books, he has a collective noun for them — “uchch koti ka sahitya” (top-notch literature). Pulp fiction can’t enter this book shop. This is the elite club of Gandhi, Vinoba (Bhave), (Ram Manohar) Lohia, Dharamvir Bharati and Shivaji Samant. Making the numbers and keeping the shelves full are assorted cooking and naturopathy books.

For Sharma and his wife, Anu, this is a second home. It’s about 8.30 am, Mr Sharma is in a baniyaan, Mrs Sharma wears a dupatta over her gown. They could well be having their morning tea in their living room.

Speaking to the Sharmas is an eye-opener. You float the cliche of reading being a dying habit and bad mouth children with phones in hand to break the ice. It doesn’t work. Pointing to the much bigger AH Wheeler bookshop that opens both on and outside the Platform No.4, he says with a smile: “They are affected by those things. My books are not available on the internet.”

You mean to say passengers sprawling on upper berths in 3 AC compartments or those squatted near the bathroom of general coaches are reading classics? “No chance, my business runs on serious readers in the city or those who take a train to buy these books. On an average, I make Rs 50,000 a month,” shouts the old man as another train screams on to the platform.

While on the topic of sales, Sharma shares Sarvodaya’s keenly contested Top 5 sellers list. The verdict is out … Vinoba, Gandhi, Lohia, Bhagavad Gita and Samant it is. What about Nehru? “Woh toh last number pe hain,” he says.

He has problems with Nehru. “Gandhiji has never been sufficiently highlighted by Congress. It’s all Nehru for them. Now, it is Modi with this Swachch campaign who is actually bringing Gandhi back in focus. While studying, I had issues with Gandhi’s thoughts but sitting in this shop, reading him changed my view.”

Gandhi’s biggest strength, Sharma says, is his push for truth. “Who has the guts to bring out a book on one’s own weakness? My Experiments with Truth is a very bold book,” he says.

History says Gandhi once used the 20- minute stopover at Ratlam to address his followers. The world might have moved but Sharma, in his cosy corner on Platform 4, is holding on to Gandhi and his principles.

Kota

Day 3: September 23, Monday (6 pm)

Close to 300 km from Ratlam, there is a village that is also continuing a Gandhi legacy — almost every home here has a charkha. Much before the IIT hopefuls descended on Kota, the city had another world-famous cottage industry that operated from a Muslim-dominated village next door. The place is called Kethun.

Kota Doria saris, with their understated designs, vibrant colours and a unique fabric woven with cotton, silk and precious gold-silver zari threads are for those with subtle taste. It’s FabIndia-meets-your neighbourhood-Chanda-Sari-Bhandar.

After speeding down the sparkling new bypass with a Mumbai sealink-wannabe bridge, watching the chain-smoking chimneys of Kota’s chemical plants, you reach the weaver’s colony. Young Imran, an artisan, is talking shop at his jeweller friend’s shop. He is among the 12 in his family who earn Rs 200 a day working on their charkha and looms.

He shares a few numbers that give the scale of the industry. “There are close to 11,000 families who weave Kota Doria saris. They cost from Rs 10,000 to Rs 1.5 lakh. It takes about 15 days to a month-and-a-half to prepare a sari, depending on the design,” says a thoughtful Imran.

His friend invites you home for a live demonstration. The lady on the loom gives a broad smile and moves away when you ask for pictures. Imran takes her place and obliges. The amused lady instructs him. She and her loom go back a long way — they spend most of the day together. “I get just Rs 7,000 for the 45 days of work I put in,” she says.

The reasons power loom-produced Kota Doria hasn’t worked is because of artists like Imran. Machines haven’t yet been able to replicate the rawness and the much-in-demand inexactness of human hands. The Kota sari has moved with time. Now, they also have a Kota Doria Khadi fabric.

Khadi brings Gandhi in the conversation. Tell the youngsters at the weaver colony the reason for this visit — your search for “Gandhi-ness” in modern India — and they nod their heads. After a strange silence, Imran chips in. “I liked what he said about Swadeshi.”

Udaipur

Day 4: September 24, Tuesday (11 am)

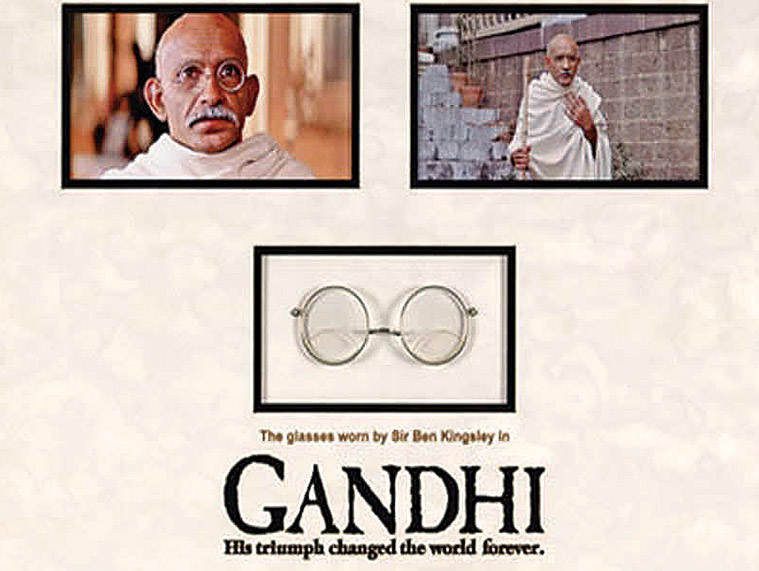

Through his eyes: The glasses used by Kingsley in the film Gandhi, now kept in the City Palace Museum, Udaipur.

Through his eyes: The glasses used by Kingsley in the film Gandhi, now kept in the City Palace Museum, Udaipur.

The guide at the City Palace Museum charges Rs 300 to make you feel miserably poor. Young Mohsin loves talking about royal opulence and waits for your reaction every time he talks about some Maharaja bathing in a giant marble tub with 1,000 silver coins, queens sitting on a 24-carat gold swing, surrounded by maids waiting to dress them with pearls, or of blue-blooded babies sleeping in all-silver cribs.

It’s at one display which celebrates austerity that he gets economical with words. Behind the glass case are Gandhi’s glasses — actually they are the ones Ben Kingsley wore in the multiple Oscar-winning Richard Attenborough classic (1982).

The story goes that the Udaipur royal family was overly hospitable to Attenborough’s crew when they were shooting Gandhi in and around Udaipur, and, as a show of gratitude, the British director gifted the now-famous glasses to Maharana of Mewar Charitable Foundation that runs the museum.

Mohsin says the Gandhi glasses get the foreigners going “Ooooooohh”. He imitates them. For the world, the image of Gandhi is the half-English-half-Indian Kingsley and what was shown in the movie — the sum total of the most famous Indian ever. The fact that it was an over-simplified eulogy is lost on those outside India.

Lawrence and his partner Cynthia live in Southampton, UK. They have seen the movie and have a sense of history. “He was a man with a slight built, he used to wear the loin cloth and those glasses with the fragile-looking frames made him look so docile. But when the world saw him fighting the British, imperialism almost became a moral issue,” says Lawrence.

You bump into the British couple again, this time at the Saraswati library inside the Gulab Park part of the palace premises. After the Kingsley glasses reminded them of Gandhi, they want some books on him. The library is shut. The notice outside the main door informs of a termite attack on the books.

They get excited on seeing the disproportionately towering Gandhi statue — one of many that dot the country — just outside the library. Cynthia asks the questions every Indian wants to ask but somehow hasn’t mustered the conviction to do so.”Was he this tall?” Her partner, minutes after talking about Gandhi’s size, answers: “He was a tall leader, I will say.”

New Delhi

Day 5: September 25, Wednesday (11 am)

While there’s a slow trickle of tourists at Rajghat, the backyard of the Gandhi Darshan arena next doors is pretty crowded. The place has the IGNOU regional centre, Khadi India’s multi-disciplinary training centre and also Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojna centre.

Anxious students and worried looking middle-aged men have queued up to collect forms, purchase books or to just make inquries. Some are discussing the job prospects of open courses, others have an interest in papad-making, washing machine repairs or candle-making and several other vocational batches that cost Rs 1,000 a week.

Auto-driver Lakhvinder Sahni, busy folding blank forms and tucking them under the drivers’ seat, is here for the Yojna that promises him vikas. He is from Champaran in Bihar. With pride, he talks about the special bond Bapu shares with his village. He has heard from friends that the two-day initiation programme helps people like him understand their business better and even suggests ideas to diversify on to other things to augment income. “For two days, I will get meals here and also roughly the money that we will lose for not driving the auto,” he says.

A sharp man, Sahni understands politics. “Kejriwal had 100 per cent of the votes back in the day. Now, the BJP is trying to woo us. We are important for Delhi elections. We don’t just vote, we are the best pracharaks. We can change an election.”

Sahni has ‘I love you Kejriwal’ painted on the back of his auto but he says he hasn’t made up his mind. He is divided between the two men who are talking about his vikas.

The man from Champaran says he first got attracted to the Aam Aadmi Party because of the old man who landed in Delhi in 2011, wearing a Gandhi topi. “We thought Anna Hazare would bring a change. It happened but it didn’t last long. They didn’t have the right plan. Gandhi understood the country better. His message was simple and he kept it simple till the end. So things worked,” trails off Sahni.

A hundred-and-fifty years after his birth, Gandhi’s greatness remains his simplicity.

Apr 23: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05