Before she came to typify deadpan Downtown New York cool, Kim Gordon was a teenager in 1970s Los Angeles, smoking pot and listening to Joni Mitchell. It was the pot that landed her in “Disney jail”. Gordon and her friend were in a cave on pirate-themed Tom Sawyer’s Island, lighting up a joint, when the Disney cops swooped in.

“They took us underground,” Gordon recalls – to a netherworld where she saw “Mickey Mouse with a walkie-talkie” and endured creepy comments from the officers: “Does your mother know you’re not wearing a bra?”

Gordon was left in a juvenile holding cell overnight. She was taking a political science class at the time, and her mind whirled. “I was writing this paper in my head about Disneyland and how fascist it was,” Gordon tells me. “It confirmed my beliefs about American consumerism.” It’s a belief she still holds. “Consumerism is killing us,” she says today.

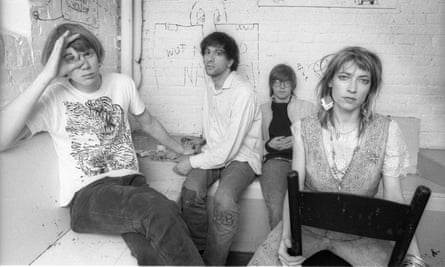

Kim Gordon v Disney is an unusually revealing punk-rock folk tale: from the earliest days of Sonic Youth, the band she co-founded with her ex-husband Thurston Moore, Gordon’s music, art criticism and paintings have been a kind of post-Warhol skewering of American myths. That sceptical eye extends to her first solo album, No Home Record – a bold mix of industrial noise, art-punk poetics and wry wit, which I’m discussing with Gordon at her sunny home in the quiet hills of LA’s Los Feliz district.

On display is a signed copy of Neil Young and Crazy Horse’s Zuma; a poster for Jean-Luc Godard’s Made in USA; and another of Darby Crash of the Germs, who are Gordon’s favourite LA punk band because of their tendency to “deconstruct” on stage unexpectedly. “That’s my kind of entertainment.” Books cover the coffee table: Claire Denis by Judith Mayne; Black Is a Color by Elvan Zabunyan; Fascination by Kevin Killian. “I used to feel this existential nausea here,” Gordon says of LA. “Now it’s a sigh of relief.”

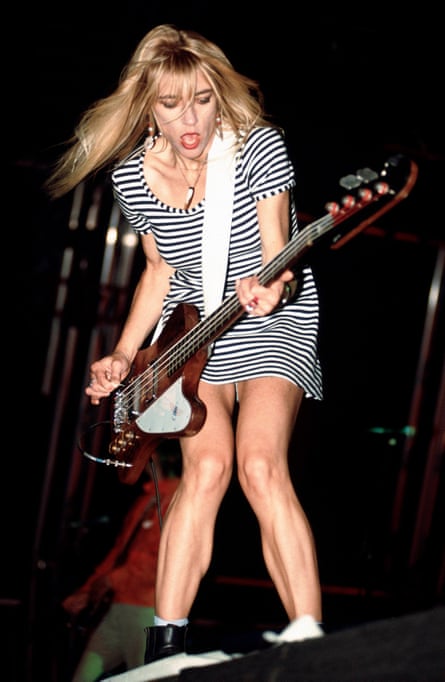

On bass and guitar, Gordon was always what made Sonic Youth punk: the inspired reach of her speak-sung vocals, her declaration that “women make natural anarchists”, her decades-long suggestion that things you wouldn’t expect can be art. She approached the mainstream with the irreverence of the underground and, in her abstracted way, tackled grim social realities, writing songs about Karen Carpenter and body image, media misogyny and sexual harassment at Sonic Youth’s record label.

Gordon has long regarded herself more as a visual artist than a musician. “Playing bass was never my desire,” she says. “It was a byproduct of wanting to make something exciting.” At first, Sonic Youth were influenced by the brash extremities of the no-wave scene: “It was like a gauntlet was thrown down,” Gordon says. “‘Here, you try to make something.’” But in the male-dominated New York noise milieu, it was Gordon who made it seem as if anyone could pick that gauntlet up – that to be an artist you just have to begin. Her career has been an inspired testament to her own maxim that at concerts “people pay to see others believe in themselves”.

Gordon and Moore’s divorce spelled the end of Sonic Youth. Her raw 2015 memoir, Girl in a Band, aired the details of his infidelity and their difficult divorce. “When I first found out Thurston had a double life, seeing the texts, I was about to go to yoga,” she tells me. “I was just looking at the time when I picked up his phone.” Gordon still went to yoga.

She has since experienced a personal renaissance of sorts, joining 303 Gallery as an outlet for her visual art and formed the immersive improv duo Body/Head with Bill Nace. She is co-editing a book of writing about women in music and has been consulting for the television show Daisy Jones and the Six, based on the bestselling novel about a fictional 70s band a la Fleetwood Mac. “I think they want to make it darker,” she says, “or that useless word, ‘authentic’.”

Gordon has lived in Los Feliz for three years, having moved from Massachusetts, where she and Moore raised their daughter, Coco, now 25. (Gordon later gives me one of Coco’s poetry zines, which includes a beautiful piece dedicated to her mother: “There’s a Crack in the Carpet – There’s a Dream in My Chest.”) Warm though still a bit elusive, at 66, Gordon says she is still not totally comfortable giving interviews to promote her work and talking about herself: “After a while, you feel like an imposter.” One of her paintings comes to mind: the dripping words Secret Abuse, Gordon’s comment on artists’ relationship to the commercial world. It reminds me of artists’ relationships to themselves, too, and she agrees: “The process is torture.”

For her solo album, Gordon worked with an outside producer for the first time, Justin Raisen, an eccentric, new-age-y Angeleno who says he made a habit of regularly chanting Gordon’s name in the weeks before the universe conspired to bring them together: he DM’d her after his brother met her at a restaurant. Gordon felt that Raisen – who has worked with Sky Ferreira and Angel Olsen – understood her “trashy, dissonant” sensibility. “It was pretty casual,” she says. “Justin just said: ‘Bring over your fucked-up poetry and we’ll make some shit.’ He was calling me Kimye.”

Named after No Home Movie, a film by Chantal Akerman, No Home Record powerfully makes the case for Gordon as an art concept herself, one who combusts notions of what music can be in order to obliquely expose the status quo. Her music feels more aligned with her visual art practice than ever – the lyrics of the vertigo-inducing Murdered Out mention matte-black spray. In her art and her music, her language is striking. She has recently painted hashtags – #Resist, #PussyGrabsBack, #YouDontOwnMe – and on No Home Record there is an abrasive anthem called Air BnB.

“It’s just subject matter,” she deflects, before adding: “What is the modern-day landscape? What is a portrait now? I’m fascinated by the pictures on Airbnb, these little utopias you can try on, to escape from one’s objects and life.” She mentions the influence of Courbet and Manet, art depicting life happening. “The most interesting art to me is always kind of a critique of the culture,” she says. “Technology gives us a false sense of confidence that everything is always evolving.”

When composing the lyrics for No Home Record, Gordon’s friend, the poet Elaine Kahn, prompted her to write down words from her everyday life. She often snatched phrases while driving around LA, looking at the signs in shopping malls. The title of the thundering closing track Get Yr Life Back was a phrase from a plastic sidewalk sandwich board promoting Get Your Life Back Yoga. “Everything is branded now: Get Your Life Back, Be Here Now, these slogans,” she says. In the album’s skittering opener, Sketch Artist, the lyric “dreaming in a tent” refers to LA’s homeless population. I ask if she is collaging reality. “A little,” she says, “or curating.” She suggests we drive around.

Gordon grew up on the other side of the city, 45 minutes away, near the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), where her father was a sociology professor. Her parents grew up during the great depression; Gordon says they never bought into consumer culture. She attended a laboratory school at UCLA that focused on learning-by-doing, which, Gordon says, “really affected the process of how I make things”.

“When I learned how to draw, I couldn’t do it,” she recalls, “I would get stuck if I just thought of the pencil on the paper. So I thought of designing the page in lights and darks. You can get so paralysed in art making. I pretend I’m doing something else.”

She drives us through MacArthur Park, past Otis College of Art and Design, where she studied in the mid-70s. Other landmarks along the way include a taco stand and her favourite carwash. “Does that say Barbie Spa?” she asks at one point.

The songs on No Home Record are also about the consequences of convenience, the breakdown of communication in relationships and the breakdown of the world. The slinking Paprika Pony features a “modern-day Adam and Eve, but they are on their cellphones”. Hungry Baby is about sexual harassment – a subject Gordon broached in 1992 with Sonic Youth’s Swimsuit Issue (Youth Against Fascism, from the same year, also feels upsettingly relevant again). “It was the tip of the iceberg,” Gordon says. I ask if she ever had to fight for her ideas. “There’s some unseen wall of faceless men that I have to climb over,” she says, “as if on a mission.”

When Gordon opens Get Yr Life Back with a statement about “the end of capitalism”, she means that the system does not work: “Trump is the ultimate capitalist, destroying everything,” she says. Her wrenching conclusion – “I feel bad for you / I feel bad for me” – is both personal and political. “People advocate forgiveness, which is a good thing, but the reality is different,” Gordon says. “You have to look out for yourself. Even the Dalai Lama says: you can be empathetic, but you don’t have to forgive someone.”

In the car, I suggest that perhaps the spaciousness of the LA landscape relates to Gordon’s use of space and rhythm in her vocal phrasings; The Sprawl, as Sonic Youth called it. She tells me that she recently listened to an audio version of Joan Didion’s 1970 novel Play it As it Lays while driving around – the tale of an anguishing woman traversing LA’s freeways alone. “Bleak on bleak,” Gordon laughs. “It really did capture that sense of driving around LA if you weren’t trying to get somewhere, but were doing a drift. And how isolating it can feel in the city.”

That classic LA isolation is something she still experiences. “I definitely have moments where I feel, not lonely, but the fear of being alone for ever,” she says – articulating each word, slowly, with space. She’ll listen to music to cope – the Steve Gunn-Truscinski Duo records, lately, and Kurt Vile – which “creates its own environment”, or she’ll do something physical, such as weightlifting.

Gordon says that No Home Record’s Earthquake is, in part, about that audience-performer relationship, and I ask if she still feels the way she did, decades ago, when she wrote, “The most heightened state of being female is watching people watch you.”

“If people are listening, you can feel this intense concentration, and it builds a level of trust,” she says. “I can be vulnerable in a way that I otherwise wouldn’t be able to be if I was just talking. There’s something about music and electricity and the free-flowing, less-contained aspect – it’s like being in the ocean. What’s the inside and what’s outside?”

After our MacArthur Park cruise, I wonder how it feels for her to be at another beginning. “There’s a sense that we work, and then we arrive somewhere, and that’s true – because if you work on something for most of your life, when you get into your 50s, you build momentum, and in a way it steamrolls,” Gordon says weeks later, by phone from the south of France, where she has an art show. “But maybe the Buddhism I read as a teenager rubbed off on me – I also like the idea of just always becoming.”