Gig Harbor’s City Council meeting Feb. 25 brought some bad news. Katrina Knutson, community development director for the town of 9,000, announced that after years of revising the city’s infrastructure laws in preparation for the arrival of next-generation 5G cellular technology — issues like how many poles can line the streets and how much the city can charge for them — the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) created its own regulations, overriding Gig Harbor’s rules.

“This is not something the city is choosing to do,” Knutson said during the meeting. “We are simply reacting to a federal order.”

Gig Harbor residents protested. Council members disapproved. Applause broke out after Councilman Spencer Hutchins said, “The FCC is an unelected body and our U.S. Congress needs to get its act together in providing some oversight on unelected bureaucratic agencies.”

Mayor Kit Kuhn, a jeweler who was elected mayor in January 2018, said during a recent interview, “They’ve taken our control to govern our own city, as far as I see.”

The FCC’s 5G Fast Plan, meant to expedite the technology’s rollout, reduces federal and municipal roadblocks to implementing those services.

The FCC limited how much cities and counties could charge companies for siting 5G cell towers. Bellevue planned on charging $1,500 per pole per year for telecom companies to put up their antennas — before the FCC mandated $270. The agency also shortened the approval time to 60 days for existing permits and 90 days for new permits.

Before the rollout of the 5G Fast Plan, cities spent the last few years gearing up for the advent of 5G by updating their small-cell siting regulations to accommodate 5G while protecting the public right of way — streets, sidewalks and parks — from an overload of small cell towers. But the new FCC rules have cities scrambling.

“If you’re a local resident and you needed a permit to upgrade your residence or jump in a business, and then you’re told that you’ve got to wait because now you’ve been bumped because we have to process this small-cell facility permit, how does the community react to that sort of thing?” said Candice Bock, the government-relations director at the Association of Washington Cities.

Gig Harbor fought it. It and 13 other cities and counties in Washington — including Seattle, Bellevue and Issaquah — are part of a nationwide lawsuit by more than 100 municipalities against the FCC.

A U.S. Court of Appeals panel in Washington, D.C., shut down part of the FCC’s plan, ruling in August that 5G cell towers could not bypass environmental or historic preservation reviews. But whether cities will get back control on the cost of permits and approving cell sites is another case that’s being heard by the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals.

Despite its part in the lawsuit, Bellevue has largely embraced 5G. In January, the City Council approved a master licensing agreement to make it easier for telecom companies to install antennas — no larger than the size of a backpack — on the small-cell poles.

“We know that in order to run an autonomous vehicle, at some point in time, you’re going to need this infrastructure in place ’cause you’re gonna need the bandwidth,” said Brad Miyake, Bellevue’s city manager.

5G is a faster wireless technology that can download high-definition movies in seconds and turn our cars, homes and blenders into “smart” devices. Establishing widespread, usable 5G, however, requires a massive update of infrastructure to work.

The 5G signals can only survive by jumping through several small-cell poles that are close together, though “close together” depends on geography, latency and numerous other factors. In cities where big telecom companies have already implemented 5G in scattered blocks, the connection can be killed by buildings or even a rainstorm.

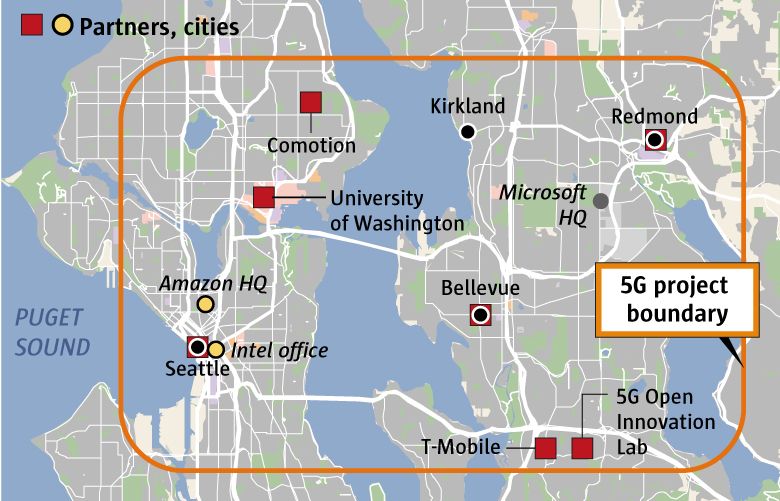

Due to FCC rules, cities now can only regulate how small-cell poles will look. Some cities like Kirkland and Seattle created prototypes for new utility poles and streetlights that could accommodate 5G antennas.

But in places like Gig Harbor, residents are worried about how the technology will look with the aesthetic of their historic downtowns.

“What can we do to make sure that that piece of technology can blend into our community?” Bock said.

Some residents also cited health concerns. Lynn Stevenson, a graphic designer who has been living in Gig Harbor for the past 11 years, avoids using technology when she can. She doesn’t walk through Transportation Security Administration (TSA) body-scanning machines. She keeps her phone on speaker and away from her ear when she’s taking a call and puts it on airplane mode every night before she goes to sleep.

She was shocked last year when she heard the FCC stripped Gig Harbor’s control to regulate how 5G would be implemented.

“We don’t have a choice,” Stevenson said. “The FCC is trying to just make things easier for big telecom companies to come into all of our cities and install all of their infrastructure on our streets and in front of our homes and in front of our schools.”

In August, the FCC concluded, after years of research, that the radio frequency exposure of 5G antennas is safe for humans. Still, many residents of Gig Harbor are skeptical. A 10-person ad hoc committee formed with the emphatic support of the City Council and Kuhn to educate the public about the health effects 5G technology.

“They make a law that you have to accept before they’ve had time to even study the health risk,” Kuhn said. “[Vaping] is a perfect example.”

The possibilities of faster internet speeds, automated public transit and augmented- and virtual- reality applications enticed cities for years. Miyake said Bellevue is looking to build out a “smart city” complete with automated water meters and improved ambulance arrival rates.

But Kuhn said he’s not so interested in that vision for Gig Harbor.

“Our whole country is trying to go toward having cars drive themselves and computers communicating back and forth, where maybe it does make some of our life easier on a daily basis,” Kuhn said. “But shouldn’t people have a choice?”

The opinions expressed in reader comments are those of the author only and do not reflect the opinions of The Seattle Times.