by Linda Gail Arrigo

語言:

English /// 中文

Photo Credit: Su Beng-史明粉絲頁/Facebook

FOR A COMMITTED revolutionary, living to a ripe old age, as opposed to dying prematurely under the axe of an oppressive regime, has its ironies. Advanced age may compel you to confront the unhappy outcomes of your own actions, see brother comrades betraying the cause and raking-in ill-gotten gains, or even make you witness to large-scale transformations that may call into question the very ideals that led to so much sacrifice. Su Beng (史明, nom de guerre for 施朝暉, born on November 9, 1918, in Shilin, Taipei)—in the last century the only living Taiwanese revolutionary forged in the active fire of national liberation movements—died on September 20, 2019, at the advanced age of 101. Though his commitment cannot be doubted, it seems that his beliefs may have evolved over time, and even more how other forces used his venerated image may have shifted, though we have no explicit words of self-reflection from him to articulate this.

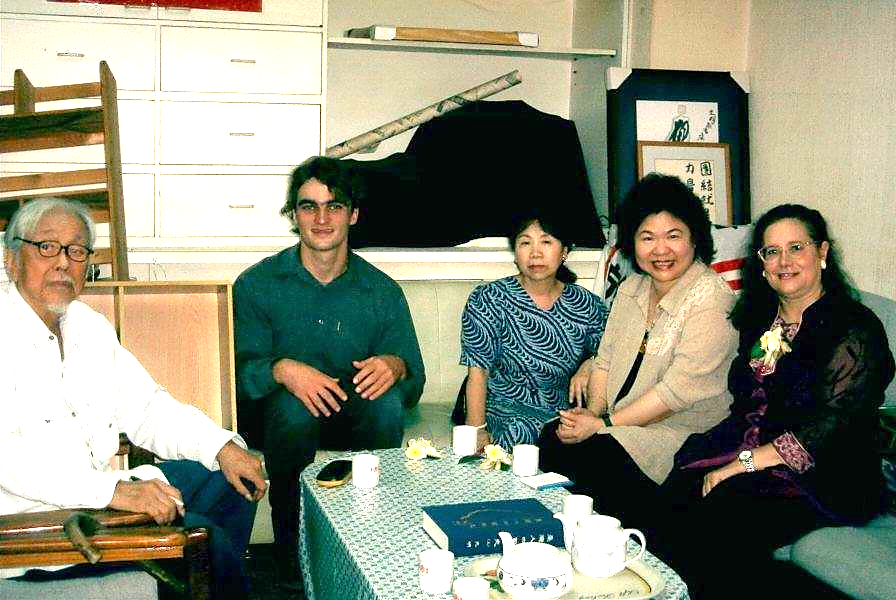

Su Beng, Stefan Fleischauer, Miyake Kyoko, Chen Chu, and Linda Gail Arrigo at Su Beng’s office on Heping East Road, Taipei in 2005. Photo provided by Linda Gail Arrigo

Su Beng, Stefan Fleischauer, Miyake Kyoko, Chen Chu, and Linda Gail Arrigo at Su Beng’s office on Heping East Road, Taipei in 2005. Photo provided by Linda Gail Arrigo

In the last several years, Su Beng has been lionized for his decades of unwavering dedication to the liberation of Taiwan and the establishment of a Taiwan nation. But the Taiwan independence movement has wanted to forget, and to paper over, the ideological basis of his disputes with other groups in post-war Japan, such as the Taiwan Provisional Government, as well as his critique of the World United Formosans for Independence headquartered in New York. Su Beng’s critique was that they represented an elitist and bourgeois conceptualization of nationalism, one that ultimately would reproduce class oppression even under rule by the same ethnic group. These ideological differences had practical consequences as well, with Thomas Liao Wen-yi (廖文毅) and Koo Kwang-ming (辜寬敏) making compromises with the Kuomintang and recovering their fortunes in Taiwan (returning in 1965 and 1972, respectively). But now his red origins and his decades of espousing “national democratic liberation” (min-chok min-zu gai-fong 民族民主解放 in Taiwanese) have been bleached to at most a light pink in the accounts done about him in his late years, as if just a personal philosophy, as at the 2017 festival on Ketagalan Boulevard for his 100th birthday—and then quite visibly at the September 21 press conference by his caretakers at the noontime after his passing. Their central message was that Oji-san, the respected elder, in his dying days supported the re-election of President Tsai Ing-wen of the Democratic Progressive Party. And nothing more than that.

He may have narrowed to focus on personal philosophy as he faced mortality, but that hardly describes the man and his mission. My understanding of his life and thinking comes from slices of conversation with him since we met at the end of 1979. Su Beng, after leaving his political science studies in Japan in 1942 to join the Chinese communist revolution, was trained by the CCP and served in gathering intelligence: He played the role of a rich Taiwanese dandy in Shanghai and gathered information for a year and a half through entertaining Japanese soldiers. He was assigned a wife by the CCP; he never knew her real name. Age 28, he got a vasectomy, he said, to prevent their work being cut short by child-bearing. Later he traveled around North China collecting information for the CCP. He was twice arrested by the KMT, but he managed to deflect detection of his spy role and was released. He had saved the life of a young Japanese woman, then only 18, who worked for a Japanese consulate in North China and who had to flee when the Japanese forces in North China collapsed at the end of World War II; they married.

After the 228 incident and massacres in Taiwan in 1947, Su Beng determined to return to Taiwan. He was also disillusioned, he often said, by the cruelty of Chinese people as he witnessed it in the trials of landlords in the communist-controlled areas, and he began to perceive Taiwanese as culturally distinct. It was extremely dangerous to pass through the lines of battle of the KMT/CCP, but he managed to return to Taiwan by ship from Shantung in May 1949, accompanied by his wife.

His old home was in Shihlin, a small town north of Taipei, and it was a well-to-do household headed by his maternal grandmother. By late 1949 Chiang Kai-shek had retreated to Taiwan and established his personal headquarters in Shilin nearby. Su Beng recruited 30 comrades and obtained a cache of weapons that he buried in the bamboo thickets on his family land, preparing for an assassination attempt on Chiang. In late 1951, carefully watching before entering his home, he realized his house was under surveillance; the assassination plot had been discovered. He went to Keelung and disguised himself as an impoverished dockworker loading bananas. It was a few months, May 1952, before he was able to smuggle himself onto a boat to Japan and hide, with razor blades sewn into the hem of his shirt to avail a quick suicide if apprehended. Arriving in Japan, he was found out by police near the dock and jailed, and awaiting deportation back to Taiwan—but he was saved by the warrant for his arrest that arrived from Taiwan authorities, thus confirming his status seeking political asylum.

His wife was back in Japan, so he obtained some security in his residence in Japan, although Japan is notorious for denying citizenship and papers to all but those of pure Japanese heritage. Su Beng started a noodle shop near a major metro station in Tokyo, Ikebukuro, and this became his source of income and base of operations. His former wife was interviewed in the film made a few years ago about his life (Su Beng, The Revolutionist 革命進行式, 陳麗貴 2016), and she said she divorced him because of “too many women”.

In the period of the Meilidao democratic movement in Taiwan (November 1977–December 1979), I was vaguely aware that there was a radical Taiwanese named Su Beng in Tokyo; he was in frequent conversation with Lynn Miles in Osaka, who ran the human rights information smuggling operation of which I was a part. I also had in my hands a copy of Taiwan Sidai (Taiwan Era, 台灣時代); its cover had a simple red line-drawing of a rising sun. It was the publication of a group of youths in North America who said they were inspired by Su Beng and his Taiwanese version of the world-wide national liberation struggle against dictators propped up by the United States. Lynn Miles, myself, and most of those involved in Taiwan human rights work, even the Christians and the Japanese, shared this background of understanding the bloody Vietnam war as a failed intervention of American imperialism; and the dictatorships in Taiwan and Korea and Latin America came from the same mold. Lynn Miles’ comrade Ron Fujiyoshi, a Japanese-American minister in Osaka who worked to protect the Korean minority, sent me Pedagogy of the Oppressed, a cherished tract. By late 1979 I could anticipate that following on the triumphant cries of the tens of thousands at the Kaohsiung Incident, “Meilidao shi lan-e!” (“The beautiful island Formosa is ours!”), repression would certainly strike. The arrests of all the leadership began early in the morning of December 13, 1979.

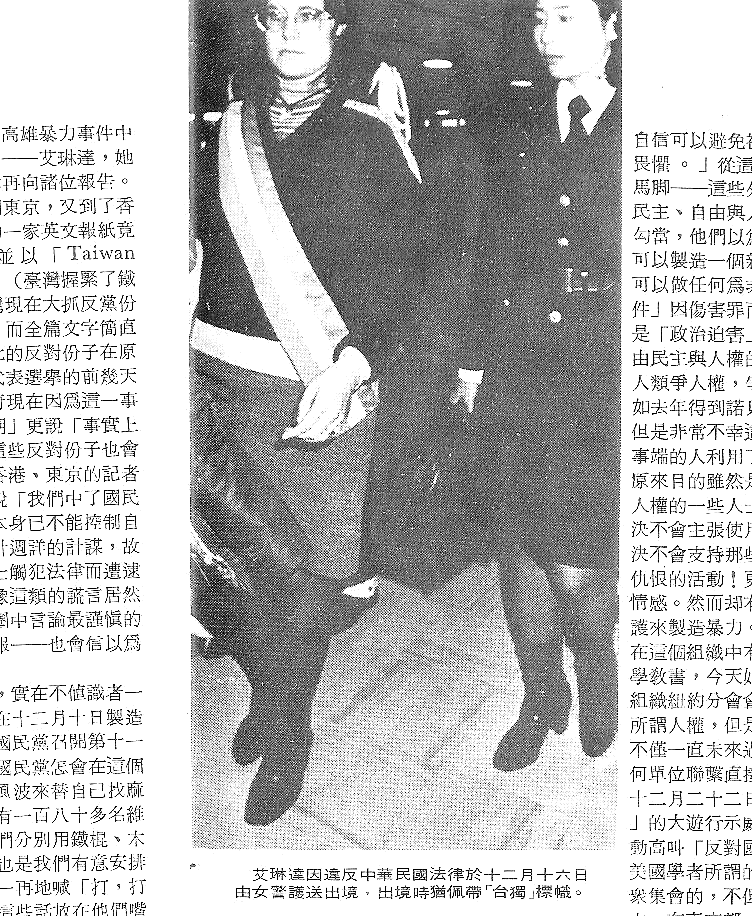

Linda Gail Arrigo under deportation on December 15, 1979, scanned from KMT propaganda pamphlet on the Kaohsiung Incident. Picture provided by Linda Gail Arrigo

As I was being deported on December 15, and was shoved through a gauntlet of reporters towards a Northwest Airlines plane at about 11 am, I threw off my jacket to defiantly reveal the banner of the Meilidao movement, a sash of grass green/golden yellow/brick red, symbolizing the Taiwanese countryside. There was a shocked silence. The picture appeared in the newspapers and on television two days later; for James Soong (宋楚瑜), head of the Government Information Office, it provided evidence of foreign agitators. Though crying hysterically on the plane, I was inwardly planning my next move—a first-hand account to sympathetic Chinese-language media and international reporters in Hong Kong—and was relieved to find by reading the ticket I had been given that the plane made a stop in Tokyo before the Los Angeles destination. I only had the US$1,000 that Chen Chu had thrown to me as she was about to meet her arrest. Before detention, I had intentionally destroyed my address book, but I had memorized Lynn Miles’ telephone number. Late that night I finally made my way to the small noodle shop of Su Beng, like a sanctuary.

The first floor was the noodle shop, perhaps only half a dozen tables. The second floor was living quarters for the workers and waiters—most actually Su Beng’s clandestine couriers and revolutionaries in training. The third floor served for the ideological education of small groups of rather ordinary Taiwanese people of miscellaneous trades that somehow found their way to Su Beng’s enlightenment and recruitment of “the masses”, a program of 10-14 days. The fourth and fifth floors were Su Beng’s quarters and the center of his communications network. This was not merely intelligence, reaching very close to the center of the KMT; he directed sabotage and demonstration bombings of KMT news outlets. He seemed proficient and professional in his simple surroundings with tatami mat floors. I felt honored to be there at this historical moment, even under the extenuating circumstances. He was just putting the final touches on the Chinese edition of Four Hundred Years of Taiwan History, the long story of foreign domination that was to be thrown off. Only the downtrodden masses had the determination to do that; the elites always turned to making profits in cooperation with the foreign oppressors.

I made a hand-drawn map of the prison island, Green Island, from the trip that Shih Ming-deh (施明德) and I had made in November 1979, and he added that to the book, bringing the history up to the current moment. I have a picture of me at his desk wearing the Meilidao sash.

In the following three days before I was off to Hong Kong, it also appeared that only the leftist associates of Su Beng dared to carry out a public protest in Japan against the crushing of the democratic movement in Taiwan; but the students wore face masks. In general, immigrants in Japan had very few rights and could be easily deported. The elite Taiwanese independence leaders there were happy to host me in their palatial apartments, but not to appear publicly.

I saw Su Beng next in Los Angeles, in late 1981, and several more times following that. He always wore jeans and a jeans jacket, a casual, lean, handsome and charismatic figure, even then with nearly-white hair and trimmed beard. It was the earliest that he had been able to obtain a Japanese passport and thus be able to travel outside Japan. He had come to financially rescue the Formosa Weekly (美麗島週報), the flagship of Hsu Hsin-liang (許信良), formerly elected head of Taoyuan County and then deposed by the KMT, and one of the core of five leaders of the Meilidao movement—but who escaped arrest by leaving Taiwan in September 1979.

On December 15, 1979, Hsu Hsin-liang had pulled together many overseas anti-KMT organizations, Su Beng’s among them, to form an alliance and issue a proclamation to “erase the Kuomintang from the face of the earth”. But as donations came rolling in, his alliance with the World United Formosans for Independence centered in New York and headed by George Chang (張燦鍙) unraveled. WUFI was not about to surrender its monopoly of control over the Taiwanese-American purse strings. Hsu Hsin-liang moved off to Los Angeles in July 1980 to form a rival center vying for the support of overseas Taiwanese.

Hsu put up a front of leftist revolutionary bravado in the magazine, like articles on urban guerilla warfare, a fake front but enough to alarm the US State Department, and he was joined by allies of Su Beng such as Kang Tai-shan (康泰山) from New Jersey and Chang Wei-chia (張維嘉) from Paris and Wang Chiu-shen (王秋森), and a spectrum of others critical of WUFI, myself included. It is a long story as to how Formosa Weekly came to the end of its finances after the hard-working volunteers, the China-friendly leftists on the staff such as Yen Chao-min (顏朝明 a.k.a. John Lee), walked out. (Remember that in those early days many idealists thought that China would support bringing down the KMT in Taiwan.) Hsu Hsin-liang was never one for long financial planning; he gambles on the short-run. But Su Beng showed up to provide money and exert impressive discipline. A pretty young woman with impeccable Marxist rhetoric but marked by her one off-center eye was also sent by Su Beng late in the process, and she stayed for several months; Ah-Fen was of course not her real name.

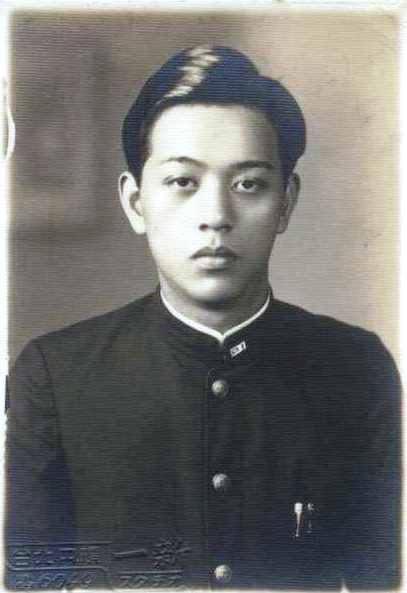

Su Beng as a student at Waseda University in Japan in 1937

Su Beng as a student at Waseda University in Japan in 1937

Hsu Hsin-liang made a pact with Su Beng for a Democratic Nationalist Alliance, as if he were the “right nationalist” in cooperation with the “left nationalist”, a combination based in standard national liberation dogma that the “national bourgeoisie” would unite with the proletariat against puppets of foreign powers, for the sake of their own economic interests. But within a few months, Hsu secretly sought alternative moneybags and dropped the alliance without notice. I persisted in questioning Hsu’s political direction, and he abruptly announced the end of meetings of the editorial staff.

Thus Su Beng came in for a scolding by the spokesman of his young disciples in North America, Taiwan Sidai, at a large but late-night meeting at the memorable summer 1982 meeting of the Western Taiwanese-American Association, in Houston, a hotbed of radical Taiwanese youth with the publication Half Mountain (半屏山). (Taiwan Sidai published their critique of Su Beng’s alliance with Hsu Hsin-liang at length in their No. 13 issue, April 1982, quoting also my pushing Su Beng to name the American imperialism behind the KMT.) The question was, how could Su Beng be taken in by Hsu Hsin-liang? Was he lacking in ideological purity? In judgment on the correct positions in anti-imperialism and democratic nationalism? I may have piped up to add some of the discomfiting details of the internal processes of Formosa Weekly as I observed them in the editorial work. To his credit, Su Beng kept his cool.

Su Beng’s 2016 autobiography recounts his first trip to the US, arriving in May 1981, beginning on page 551. He states that he needed a channel to propagate his message through a publication, but was busy with his underground organization. And he denounces Hsu Hsin-liang for his slack work attitudes and lack of political honesty. He cites a specific exchange with Taiwan Sidai, on pp.573-574. Taiwan Sidai demanded that he stop financial support for Formosa Weekly and instead form a genuinely progressive alliance with them and others; it had a resolutely anti-American position. Su Beng calls Taiwan Sidai Stalinist and out of touch with the practical needs for solidarity and advance of Taiwan nationalism, and said he would accept the assistance of the United States to counter China.

In retrospect, I would say that Su Beng, like most leftists who must imbibe their Marxism through Chinese-language sources, did not fully grasp the viciousness of US imperialism in Latin America and the Middle East, as well as in Vietnam, the world-wide confrontation of forces under the Cold War, or the American capacity for deflecting class struggle with calls for electoral democracy and “freedom”.

The background of this exchange is that Taiwan Sidai challenged World United Formosans for Independence in a concerted effort beginning June 1980, seeking influence over the middle-class Taiwanese-American community, but even more on campuses. It set off a debate on the meaning of “nationalism” and introduced the concepts of nationalism and citizenship as utilized by national liberation movements worldwide, a rhetoric that is familiar to the proponents of social movements in the 1960s, a definition of political common cause rather than an ethnic definition. This definition was generally accepted by the Taiwanese-American community, in theory. However, Taiwan Sidai faded away in 1987, soon after the hope for non-violent change in Taiwan emerged with the formation of the Democratic Progressive Party in Taiwan. The long-term impact of Taiwan Sidai may not be externally apparent, but many of those students who were influenced returned to Taiwan to take up environmental and labor movements—and Su Beng who was the mentor of Taiwan Sidai should be recognized as well for this.

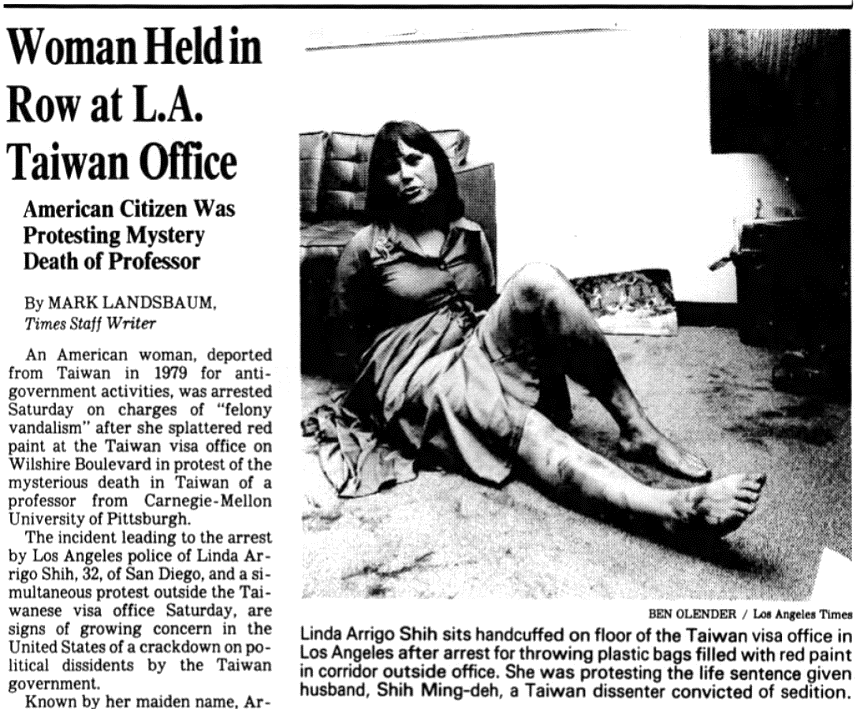

In fact, Professor Cheng Wen-cheng (陳文成) of Carnegie-Mellon University was a leading member of Taiwan Sidai, and he was my host in Pittsburgh a few months before his July 1981 murder by the Taiwan security forces. Su Beng commended me for throwing red paint in the KMT office in Los Angeles in protest on July 18; I was put in a choke-hold by their flunkies as they mulled over kidnapping me to Taiwan, and I was actually relieved to see the Los Angeles police coming to arrest me 45 minutes later.

LA Times article on the protest action

LA Times article on the protest action

Not very long after the Houston meeting, I prepared to renew my graduate studies by entering the Department of Sociology, State University of New York at Binghamton, for Fall 1983. I had sought out the most Marxist and Third World-oriented department in the United States, to finally get an intellectual understanding of world revolution. I was surprised to find several people I knew well already there: Ka Jiming (柯志明), son of the leftist political prisoner Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) and now at Academia Sinica; Ms. Su Ching-li (蘇慶黎), formerly editor of China Tide; and Dennis Engbarth, another of Lynn Miles’ human rights correspondents in Taiwan in 1977-78.

Our classmates were exiled dissident intellectuals, some with experience of underground work, rebellion, and imprisonment, from Brazil, Ethiopia, Grenada, Haiti, Iran, India, Korea, Namibia, Thailand, Turkey, etc. But we were mostly exposed, academically, to the egghead and disillusioned version of world revolution. By the early 1990s, the evolving judgment of the intellectual left was that there was no longer any “national bourgeoisie” to be found supporting national liberation movements because capitalists were substantially globalized and inter-invested. Moreover, as expounded by Immanuel Wallerstein, founder of our department and “world systems analysis”, the core of the world economy shifts gradually over time as it seeks new markets and cheaper labor, and the United States was been, relatively, slipping, and wasting its resources in reckless imperialist domination, while parts of Asia were rising.

In fact, Marxism does not generally look highly on nationalism, which could be called a kind of mass identity or tribalism that is most often rallied by states for repressive ends. By Hobsbawm’s analysis, whether nationalism aligns with or opposes mass entitlements is shaped by the historical context. My own 1992 academic study found that both right and left movements try to capture the popular momentum in shaping their rhetoric on nationalism, and this is a common struggle within nationalist movements. In the 1920s and through to the 1960s mass movements in colonies aligned easily with socialist nationalism because the oppressors were obviously foreign powers, whether English, French, or Japanese, etc. But especially after the fall of the Soviet Union, nationalist movements have been drifting back to conservative ethnic essentialism and losing the previous platforms of state central planning and mass citizen entitlements.

We can see such a shift in the history of Taiwanese nationalism, from Chiang Wei-shui (將渭水), 1888-1931, the doctor who championed mass movements under Japanese colonialism, to World United Formosans for Independence with its base in Taiwanese-Americans, many working for US defense industries. It is not surprising then that Taiwan is not now fertile ground for national liberation ideology. Aside from the KMT’s long rule and anti-communist indoctrination, the fortunes of Taiwan’s economy have long been hitched to its ancillary role in the expansion of US and Japanese capitalism. Add to that the bombastic Chinese nationalism and menace of invasion by the Peoples Republic of China, which is still nominally a communist country, and the increasingly conservative political direction of the Taiwan independence movement in general, as well as of the Democratic Progressive Party, seems overdetermined.

Su Beng smuggled himself back into Taiwan in 1993, and he set up an office on Heping East Road not far from National Taiwan Normal University. He continued with the training programs as he had run in Tokyo, and probably on a larger scale since there was now little danger of retribution from the secret police. I ran into a loose group of working-class people, his trainees though not under his direction, who met at the corner of Daan Park once a week for standing political discussions. He had a number of assistants. I visited him a few times, on one particularly memorable occasion in 2005 with Ms. Chen Chu (陳菊), Ms. Miyake Kyoko (三宅清子), a central founder of the Japanese Association to Rescue Taiwanese Political Prisoners, whom Su Beng had long known in Tokyo, and Stefan Fleischauer, an enthusiastic young German who wrote his thesis on 2-28.

Su Beng’s written materials were much as before, with his organization’s symbol a thick red arrow pointing up, plus a pyramid-shaped diagram representing a class analysis of Taiwanese society. The tip was a triangle cut off from the rest of Taiwanese society, identifying the oppressors. It included both the KMT party and its minions of mainlanders at the top, and a lower layer of the triangle that was the “big” Taiwanese bourgeoisie, though the small and medium Taiwanese businessmen below that were included in the range of Taiwan nationalists. (This chart is reproduced in Su Beng’s autobiography, p. 563, dated 1984.)

But his rhetoric about the “bitter laboring masses” (勞苦大眾), the standard verbiage of 1920’s national liberation movements, began to sound tinny amid the prosperity of full-employment 1990’s Taipei, as coffee shops sprouted on every corner and high-rise buildings jutted up clad in granite and marble. I always wondered how someone like Su Beng who had faced life-and-death situations on the edge of survival could make sense of this contradiction.

Shih Ming-hsiung (left), Linda Gail Arrigo (center), and Su Beng (right). Picture provided by Linda Gail Arrigo

Shih Ming-hsiung (left), Linda Gail Arrigo (center), and Su Beng (right). Picture provided by Linda Gail Arrigo

Curtis Smith (史康迪), an old friend of mine in Taiwan, a Canadian and also now a ROC citizen, has also been puzzled as to why in recent years Su Beng has been portrayed as only a Taiwan nationalist. He wrote to me last week, “There is a riddle concerning how and when Shi Ming was turned. When I interviewed him in his Heping East Road office in 1996, he insisted that the people of Taiwan were among the oppressed nations of the world (and he specifically named Palestine) struggling for independence in the face of US imperialism. He repeatedly praised the aims and tactics of the PLO in battling Israel. He stated that he believed in Marx-Leninism and that class struggle would set them free.”

In another decade, Su Beng moved to Xinzhuang with his devoted followers and was about the only Taiwan independence advocate who kept up direct action in public demonstrations against the spokesmen of the Peoples Republic of China who began landing on Taiwan. In public lectures and books, he continued to propagate the 1970’s rhetoric of national liberation, but it is questionable what relevance it could have for the general Taiwanese audience. However, as his triangle diagram had depicted, from the late 1980s the Taiwanese bourgeoisie sought to increase their profit margins by using cheaper Chinese labor in the production of consumer exports to the United States. Hsu Hsin-liang, for a while chairman of the DPP, was, in fact, the foremost political advocate of “Go West!” (to China) for Taiwanese business, and he extolled the comprador role as a kind of Taiwanese superiority in his book Rising People (新興民族), 1995. Even as Taiwanese nationalism flowered under President Chen Shui-bian after the year 2000, the flow of high-technology Taiwanese capital to China accelerated. Perhaps the forces of the world economy were overwhelming. Or perhaps there was insufficient political will to avoid stepping into the trap.

About seven or eight years ago, twice, at public banquet occasions, I asked Su Beng what he thought about American imperialism. The world press had long reported on ongoing carnage following the US invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. He said simply, both times, that Taiwan had to thank the US for preventing invasion by China. Almost any Taiwan independence advocate would say the same. And, I would say, so much for the internationalist perspective and solidarity of national liberation ideology!

Perhaps Su Beng did alter his line in the face of the prevalent conservatism of Taiwan society, or due to realpolitik—but does the way Taiwanese slavishly obey the United States bring any future? At least Taiwanese could learn the bitter lessons given to Tibetans and now Kurds, that the US often carelessly betrays small nations. It was the US that stomped on President Chen Shui-bian and called him a “trouble-maker” after he broached the topic of a popular referendum for Taiwan’s future. At the same time, the US was supporting a popular vote to legitimize Iraq’s new constitution. But Taiwan is, anachronistically, still officially calling itself “The Republic of China”. And according to my sources of information close to the DPP, the US secretly requested President Tsai Ing-wen to suppress the “Happy Island” demand for a referendum. Though of course she also does not want to ruffle the business community, which would blame her for riling China.

Is there any way out of the trap? At this point, I would not claim that there is, under any ideology or world view. But I think that Su Beng deserves the recognition of his original pure red convictions, if necessarily also with realization of how a time warp that can make a mockery of all our ideals and aspirations.

Selected References

- LG Arrigo, 1992. “Colonialism and the Rise of Nationalism in Asia”, manuscript November 1992. Area Paper for Ph.D. program at Department of Sociology, State University of New York at Binghamton.

- 1994. “From Democratic Movement to Bourgeois Democracy: The Taiwan Democratic Progressive Party in 1991”, pp. 145-180 in The Other Taiwan: 1945 to the Present, ed. Murray Rubinstein, 1994. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe. Taiwan in the Modern World Series.

- 1996. “Labor Rights and Nationalism: The Case of Taiwan”, with co-author Jason Chin-Hsin Liu, BIDOM No. 134, Nov.-Dec. 1996, pp. 14-18.

- 2006. “Patterns of Personal and Political Life among Taiwanese-Americans”, Taiwan Inquiry, Vol 3.