Nasreen Askari had no interest in fashion when she was growing up. “I was deeply ugly, slightly sporty and slightly nerdy. That summed me up,” she says of an adolescence spent in the elite schools of 1960s Karachi. But if Askari, now nearing 70 and elegantly draped in Issey Miyake pleats, has anything to do with it, then the traditional textiles from her home province of Sindh will be appreciated not just as quirky national heritage but as art in their own right.

“Even now the antiquity of Sindh’s textiles tradition, which goes back to 5000BC, is terribly under- exposed and not studied,” she says. “It has been subsumed under a generic classification of Indian art and culture if it is appreciated at all.”

Askari has dedicated her life’s work to the preservation and elevation of the bold, dramatic and painstaking embroidery and block prints of the artisans in Pakistan’s second biggest province. Her homes in Knightsbridge and Karachi, where she lives with her husband Hasan, a retired banker and former trustee of the British Museum, are stuffed with fabrics, textiles and miniature paintings from the subcontinent. The couple have spent 50 years collecting and curating and are now preparing to publish a coffee-table book archiving a breathtaking visual history that would otherwise be lost.

The Flowering Desert: Textiles From Sindh reveals an alternative narrative of the region best known abroad for the unruly, sprawling mass of its capital city, Karachi, and the drama of its most famous family, the Bhuttos. By shining a light on the arts and crafts of its rural hinterland, the Askaris aren’t just aiming for international recognition but reverence at home for a tradition that has often been overlooked or dismissed.

“People have migrated to the cities for survival and employment,” she explains, while handing me ornate, delicate pieces from her 400- plus collection. “Women don’t have the time or the skill or the energy to work for weeks or years on making these elaborate embroideries. Now there is electricity, television, modern life. Machine embroidery has taken over or they use imported thread, which doesn’t have the same texture.”

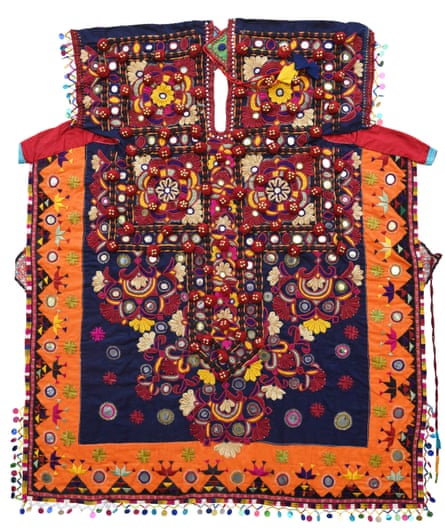

Askari’s enthusiasm and reputation in her field are unparalleled. She still has her very first Sindhi blouse – a gaj – bought from “a young lad in Hyderabad” who now has a shop in Karachi and is a major supplier for dealers abroad. But how did a shy and awkward former dentist and mother of two become one of Pakistan’s most ardent cultural ambassadors?

“My interest started quite a long time ago, some time in 1970,” she says. “I went from the privileged schools of Karachi to university in Jamshoro, a complete wilderness, and catered for patients from all over Sindh. I saw costumes and textiles I’d never seen before, there were whole vocabularies communicated by the patients I saw: they wore what they were.”

Through the motifs, colours and styles stitched on shawls and shirts, Askari learned to decode whether a woman was married, had children, what tribe she was from, her family stock, language and traditions.

“They held great store by their textiles – they were great embroiderers, they all lived with their livestock, very rural and very traditional. That’s where my fascination began.”

Askari practised as a dentist in London, where she met Hasan, and later in Hong Kong and Tokyo, where the couple lived before settling back in London in the early 90s. She studied Asian civilisation at university while living in east Asia and on her return to the UK became a regular visitor to the V&A.

“I’d heard the governor of my old private school had endowed his collection of Sindhi artefacts to the museum and I wanted to see them.” At first, “nobody had a clue” what she was talking about or where the collection was located. Eventually, she got a call inviting her in to have a look at the reserves. I was completely blown away. These were museum pieces that no museum in Pakistan had. I said: ‘These are so beautiful, why don’t you show them?’ And they said: ‘Oh, nobody is interested in Pakistan and we have no one who could curate it’.”

Askari immediately nominated herself and spent two years in the basement of the V&A working to prove her instinct right. The project was a testament to her passion rather than her experience, of which she had none. But by 1997 she mounted what was considered the first major international exhibition of Pakistani textiles: Colours of the Indus was scheduled to run for three months at the V&A; it was extended to seven and then went on to the National Museum of Scotland.

“And then it was endlessly copied,” says Hasan, proudly. “Suddenly you had Colours of Rajahstan, Colours of India and so on.”In the same year, which also marked 50 years of Pakistan’s independence, she moved to Karachi to found the Mohatta Palace Museum, dedicated to the arts of Pakistan, where she still works as its director.

“Within textile arts, Sindhi works stand very high. It’s just so little known and understood,” says Askari. “The greatest strength is not just the skill but the authenticity. These people come from rural cultures where there is real meaning to what they make.”

In modern Pakistan, where buying ready-made apparel “off-the-rack” versus tailors hand-making and stitching clothes for customers is only a very recent phenomenon, Askari credits Khaadi – which is the first Pakistani brand to have stores in UK shopping centres such as Westfield – for making the national’s artisanal arts popular again. “They have done amazing things. Arguably they have diluted the craft but they have bought design and tradition to the marketplace and made it accessible.”

Whether they are explaining the traditions of akraj, wooden block printing, or silk stitching, the couple’s urgency is palpable. “It is urgent,” says Hasan, “because our creative juices and energy won’t run forever. It’s a small point but it’s also interesting that in Pakistan, there is the beginning of an appreciation of its historical Hindu connection and the contribution of the diversity of our cultures. In India, the exact reverse is happening – there the Modi administration’s efforts to re-label Indian history is to fit in with their own narrative.”

The Askaris ardently believe in the “soft power” of culture. “In a sense, I hope this book will go some way to show that,” says Nasreen. “It also crystallises Pakistan in my own mind, and so therefore I am able to give it form to others.”

The Flowering Desert: Textiles of Sindh is published on 1 November by Paul Hoberton, London, and Mohatta Palace Museum, Karachi, RRP £30.00