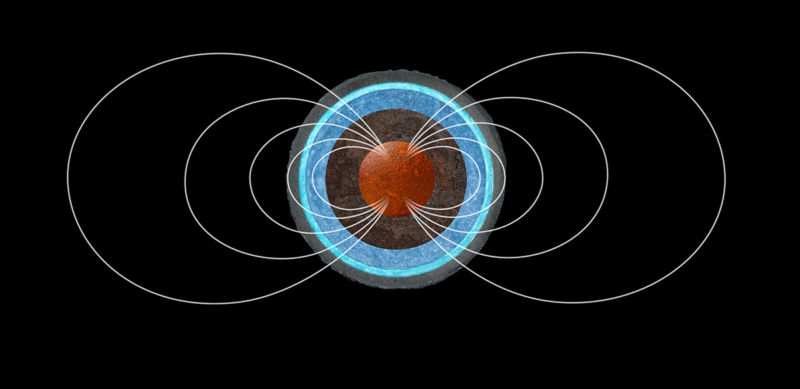

We live on the most comfortable of planets. It may not be too visible, but the Earth's magnetic field plays a critical role in maintaining that comfort. The remaining rocky planets in our Solar System have much weaker magnetic fields and, as a result, are subject to a constant bombardment of high-energy particles from the Sun. Yes, our biosphere owes a great deal to a pool of molten iron at the core of our planet.

Yet the core presents something of a puzzle to us. The extreme conditions make it very hard to understand: we cannot conduct experiments that fully replicate core conditions, and our measurements are indirect, since no one wants to visit the core. That leaves us with computer models. Until recently, these models were rather limited. However, ever-increasing computational power is starting to reveal that the core has an interesting story to tell.

Onions not parfait

Our planet, like all planets, is born of violence. The aggregation of mass during its growth came via large impacts and oceans of molten rock. Gravity provided a kind of filter: the heavy elements like iron were pulled to the core, while light elements like silicon and oxygen were left floating on the top.

That simple picture provides the basic stratification of the Earth, but it does not explain the magnetic field. To do that, you have to include convection, which drives currents of liquid iron that generate a magnetic field. Convection, however, requires a temperature difference between the center of the core and its outer boundary. But the heat conductivity of an iron core makes it difficult to imagine that the temperature difference was sufficient to get convection underway.

To muddy the liquid iron further, convection currents imply a certain amount of mixing. So, we have a few different processes at play: gravity drives stratification while convection mixes the layers. Then, as the elements mix, solubility and chemical reactions come into play. Was oxygen retained in the early core thanks to solubility and chemical reactions? Does the presence of oxygen change heat flow, which would then change the strength of the magnetic field?

To understand these processes, you have to perform a very difficult set of calculations. First, the quantum chemical properties of the elements need to be calculated to determine what the lowest energy configuration of a mixture is—how much oxygen should be in the iron. Then that calculation has to be combined with how the elements and molecules physically move around. All of these calculations have to be performed at temperatures of around 5,000K and pressures of 160GPa.

Bring on the GPUs

Twenty years ago, you could not combine these calculations in any useful way, because there simply wasn't enough computational power available. Ten years ago, these calculations were viable under limited circumstances. And now they can be applied at temperatures and pressures that are relevant to the Earth's core and with sufficient scale to be meaningful (though still very small-scale).

To demonstrate this, a group of researchers examined oxygen transport and retention by the core. The researchers showed that the early core probably had considerably more oxygen than the present-day core. However, that oxygen may have formed a stratified layer of oxide (though at these temperatures, it is probably better to think of this as a mixture of iron and oxygen) just below the boundary between the core and the mantel. The stratification and accompanying reactions reduces the amount of heat flow out of the core. This, in turn, weakens the convection currents that drive circulation required for forming the Earth's magnetic field.

In summary, these calculations make something that was already difficult to explain a little more difficult to explain.

The researchers note that, although the core of their results is reliable, some of the conclusions are tenuous. For instance, the partitioning of iron and oxygen containing iron is solid. However, the model does not have sufficient scale to determine if the stratification is stable when exposed to convection currents in the core and thermal gradients in the mantle above. These sorts of calculations require a different type of model.

The researchers also did not include the influence of silicon and magnesium in their calculations. These are the other two big elemental contributors and could significantly change the results. The researchers were treating their calculations as a proof-of-principle for the technique. The next step is to perform a new set of calculations that have a more realistic mix of elements. Then we might get a clearer picture of the chemistry of the early Earth's core.

Physical Review X, 2019, DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevX.9.041018 (About DOIs)

reader comments

65