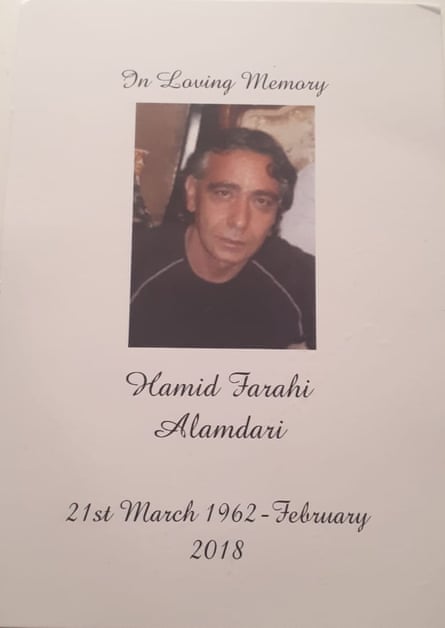

Hamid Farahi Alamdari was full of stories. When he was living out of his car in a Tesco car park in Harlow, Essex, he told anyone who would listen about his exciting past as an avionics engineer, Iranian war veteran and physicist. Then there was his pièce de résistance: the time he was shortlisted to be Stephen Hawking’s assistant. “I took it all with a pinch of salt at first because he was telling me all these stories and I could tell he was a drinker,” says account manager Adam Protheroe. “He could have been anybody. He could have told me that he was the king of Iran and I wouldn’t have known any better.”

Protheroe became close friends with Hamid in 2017. “I’d seen him around and he was living in a Peugeot 206 that was parked up just around the corner. I came back a couple of days later with a bag full of clothes and bits and pieces and socks. My wife cooked him a nice meal and I took it down to him in a little box and started talking to him from there.”

He would eat with him, take him to appointments and raised more than £700 to get Hamid accommodation in the winter that followed. Protheroe wasn’t bothered whether he was telling the truth or not. He liked Hamid, and who wouldn’t spin a yarn or two when life had dealt them such a bum deal?

Q&AWhat is 'The empty doorway' - the Guardian series on people who died homeless?

Show

726 homeless people died in England and Wales in 2018, according to the latest ONS figures. Over the next few months, G2 and Guardian Cities will look behind this statistic to tell the stories of some of those who have died on Britain’s streets. We will tell not just the story of their death, but the story of their life – what they were like as kids, what their dreams were, their hobbies, what people loved about them, what was infuriating. We will also examine what went wrong with their lives, how it impacted on their loved ones, and if anything could have been done differently to prevent their deaths.

As the series develops, we will invite politicians, charities and homelessness organisations to respond to the issues raised. We will also ask readers to offer their own stories and reflections on homelessness. We want the stories we tell to become the fulcrum of a debate about homelessness; to make a difference to a scourge that shames us all.

It is time to stop just passing by.

Protheroe was by no means the only one to fall for Hamid’s raffish charm. Many of the locals had a soft spot for the bearded stranger with the laughter lines and exotic accent. Hamid chatted to his new friends about literature and science, spiritualism and martial arts, Iraq and war, pretty much anything. And then one day he was gone. Just as he had arrived unannounced, he disappeared. In February 2018, Hamid was taken ill and moved into emergency accommodation. He died there alone. Like two-thirds of homeless people, Hamid suffered with addiction. And like many people who die homeless, he looked far older than his 55 years.

Harlow is one of the new towns built after the second world war to ease overcrowding in London. In its early years it had a thoroughly modern can-do feel to it, boasting Britain’s first all-pedestrian shopping precinct and first modern high-rise residential tower block. But more recently it has fallen on tough times. This year, Harlow’s Conservative MP, Robert Halfon, suggested the town had become a dumping ground for London councils, which have sent hundreds of “troubled families” to live in converted office blocks in his constituency. The last census, in 2011, showed that Harlow had higher unemployment, less home ownership, lower educational qualifications and poorer health than the average for both Essex and England.

In June, however, Halfon said things were looking up for the town. “The news that homelessness is at its lowest level since 2010 is a real step in the right direction,” he declared. Halfon quoted the absurdly low figure of five homeless people, and was soon corrected by a local Labour councillor, Tony Edwards, who pointed out that the figure referred to rough sleeping not homelessness, and that in fact more than 4,500 people were on the housing-needs register in Harlow and about 400 people had made “homeless” applications in 2018/19. That paints a very different picture. It means that, with a population of 85,000, 5.3% of people in the town are waiting to have a housing need met.

It is 18 months since Hamid died, and we meet Protheroe in the Tesco superstore cafe where he and Hamid would often get together for coffee and bacon sandwiches. Protheroe is business-like and comes straight to the point. He says he doesn’t want us to get the wrong impression; he’s not a do-gooder. He considered Hamid a friend rather than a charity case. “I’m not a selfish bastard, but I’m not out to help everybody I can,” he says. “If anything, I’ll help animals more than I’ll help people. I just got to know Hamid and we became mates.”

In 1981, when he turned 19, Hamid was conscripted into the army to fight in the Iran-Iraq war

Hamid told Protheroe he had ended up homeless in 2017 after selling his pension in a dodgy deal and then running into money troubles. But even here there is a mystery. Unlike most people living on the streets, he still had savings in the bank. He camped in woodland close to Tesco until his tent was set alight. Protheroe says Hamid told him that teenagers were responsible, but he didn’t like to talk about it.

Soon after this a Harlow local gave Hamid the old Peugeot 206. He parked it by Tesco and moved in. The interior of his car-home was crammed with donated clothes and books – science books, spiritual self-help guides, novels, all sorts. The only space left for Hamid was the passenger seat. Protheroe thought his friend might be an eccentric hoarder.

Hamid told him he spoke seven languages, that he had a PhD in astrophysics and theoretical maths, and mentioned the job he almost got with the late Prof Hawking. He also talked about fighting in the Iran-Iraq war, showed him photographs of members of his platoon who had died, and told him he suffered from terrible flashbacks. That’s why he drank, he said – to blot out the memories. Protheroe is surprised by how well they got to know each other in such a short period of time. He would find himself visiting Hamid at night to make sure he was OK.

Although Hamid was a good deal older, 41-year-old Protheroe found himself playing a paternal role. He would often tick Hamid off about the state of his car-home. “I’d open up the car door and he’d been smoking roll-ups in there. I said you’ve got to sleep in there, and there’s smoke billowing out. It wasn’t the kind of car I would have liked to have slept in, if I’m being honest. Hamid wasn’t very tidy. I’d have a go at him – ‘Sort yourself out, you look like a sack of shit, you need to run a brush through your hair.’ I’d just have a dig at him and we’d have a bit of back and forth. He’d laugh at me, and take the piss.”

Like Protheroe, Chrissy Sorce is almost apologetic about befriending Hamid. “I don’t know why I took to him. I don’t go out and randomly do that to everybody. It’s just something about him – he was likable.” Sorce, who is 51, works at a car-rental firm based in the industrial park next to Tesco. “He parked the Peugeot behind our workplace, and I just started chatting to him on my fag breaks,” she recalls.

Sorce talks about his fondness for scratch cards – “He was always trying to win millions, bless him” – and how she stored books for him in her daughter’s shed to free up space in the Peugeot. “They were quite intellectual books. He was very educated. But something obviously went wrong somewhere along the line, which can happen, can’t it?”

Hamid told Sorce many fascinating and funny stories. But for all that, there was a terrible vulnerability about him, she says. “It was all a fake, really, because at the end of the day he was still lying in that car and sleeping in the freezing cold.” Sometimes when he was drunk he would weep and tell her he wished he was dead. Sorce says she told him not to be daft, and to take any opportunity that came along. But she admits, at this stage of his life, few opportunities were coming his way. “I think the council could have housed him. He could have been put in a room a lot sooner, surely. They all knew where he was.”

Adam Protheroe says he often used to tell Hamid off about the state of his Peugeot home. Photograph: Adam Protheroe

What she most liked about Hamid is that he didn’t want anything from her. “He never even asked me for a pound.” She pauses and smiles. “He did ask me to go out for dinner, though, but I had to let him down and say no. I think he liked the women. He would go into Tesco and chat to them.” She once did his washing for him, she says. “I washed and ironed everything. I said to him: ‘Do you want me to do any more?’ But he never gave me any more to do. He was proud. After I did that, he went out and bought me washing powder to replace what I’d done. I told him not to bother, but he did it anyway.”

She knows some people couldn’t understand why she wanted to help him. They said it straight out to her. “When I took home his washing – and yes, it really did stink – one of my managers said: ‘Eeeeugh, how could you wash all his clothes?’ I said: ‘Easy, you just put them in the washing machine and take them out.’” Sorce says she couldn’t help thinking it could just as easily have been her living in that car. “We’re all one pay cheque away from being homeless. You never know what’s going to bring you down, that’s how I see it.”

At times, she says, Hamid seemed confused. She and Protheroe believe he had early-stage dementia. As for his stories, she didn’t know what to make of them. “You never know what’s true and what’s not, do you? You just go along with it.”

Both Sorce and Protheroe were anxious that Hamid should take care of his appearance. They believed that this, coupled with sobriety, could be the difference between him getting a council home or not. That’s why Protheroe ended up taking him to his barber’s one day. “Hamid was attending an alcohol dependency therapy group in Harlow,” says Protheroe. “The idea was that, if he demonstrated he could get off the booze, they would recommend that the council should give him somewhere to live. I was trying to sober him up and make him look a bit more respectable. So I took him to my barber. Hamid had this big old white Father Christmas beard and he took all that off, cut his hair and he looked like a different person.”

It was at the barber’s that Protheroe began to suspect Hamid may have been telling the truth about his academic background. “My barber is a very intelligent guy, and him and Hamid were having conversations about string theory, this theory, that theory. It was really bizarre to hear Hamid coming out with these things.”

Hamid never did get council accommodation, but Protheroe says in some ways he was his own worst enemy. The Harlow homeless project Streets2Homes tried to find a place for Hamid to live. “They’d say: ‘We’ve got a room for you, but you can’t drink or smoke in the room, and there are all these rules and regulations.’ Hamid was like ‘Nononono, I’m not having that.’ And he just wouldn’t do it. If you want help, first of all you’ve got to help yourself. Hamid was like: ‘I’d rather sit in my car and drink and smoke.’”

Protheroe admits he may be being tough on his friend – insisting that an alcoholic does not drink in his own home is a big ask. Hamid may well have benefited from the Housing First model, whereby homeless people are provided with a home and then addiction issues are addressed with wraparound support. Streets2Homes declined to talk to us for this article.

There was also something about the car-home that made Hamid special. He was well known to Tesco customers and became something of a local celebrity. Hamid and his Peugeot had become a landmark. Protheroe reckons Hamid had good reason to be wary of council accommodation. He tells us of the time Hamid was robbed while staying in a hostel. “He had his bloody pin number written on his bank card and whoever it was that stole it from the hostel emptied his bank, absolutely emptied his bank. So I was on the phone to his bank and tried to get it all sorted out. He had a couple of grand in the bank; that was what was left over from his pension.”

Sorce thinks Hamid declined offers of housing because they were not permanent, and he felt he would be even more exposed there. “He wanted to steer clear of people who were similar to him,” she says. Hamid told her he was offered a place at Terminus House in Harlow, a grim-looking block of flats often described as a “human warehouse” where hundreds of residents, sent from councils across London, are crammed together in tiny flats. Halfon has referred to the practice of rehousing families from London in his constituency as “social cleansing”. The building made headlines in July because of a drugs network operating nearby, and police figures show that crime within a 500-metre radius of Terminus House rose 20% in the 10 months after it opened.

Rather than accepting a place in Terminus House, Hamid returned to his silver Peugeot, carried on smoking and drinking, and continued to be berated by his good friend for his slovenliness. Protheroe says that somehow Hamid, for all his bad habits and obduracy, brought out an incredible generosity in the Harlow community. One day Hamid broke the key in the lock of the car door, and Protheroe posted a shout-out on Facebook for help. “This guy got in touch, came down, and sorted him with a key. It was normally a £200 job, but he did it as a gesture of goodwill.”

When the weather turned and Protheroe was worried Hamid might get hypothermia, he set up a GoFundMe page. “A kind-hearted girl phoned me up around midnight, and said: ‘I can’t stop thinking about this guy. I want to come out and help him.’ I said: ‘Right, I’ll get out of bed and come and meet you.’ She and her husband drove down in a hundred grand Mercedes AMG Jeep. They paid 400 or 500 quid to put him up in the Park Inn for a week.”

Another woman turned up with a huge biscuit tin crammed with cigarettes. “It was filled to the brim. There must have been a couple of thousand roll-ups in it.” And soon after it became apparent that there was no longer room for Hamid in the Peugeot, another miracle happened. “A guy rocked up with an Audi estate car, which was like twice the size of his existing ‘premises’. He parked that up behind, and the Peugeot became a storage facility for all the junk while Hamid moved into the Audi.”

Family and friends at Hamid’s funeral in Harlow, 4 May 2018. Photographs: Martine Xerri/BPM Media

It’s a story deserving of a happy ending. But of course it didn’t have one. Eventually, as he became ill, Hamid did accept help, and during a cold snap in February 2018 he was provided with emergency accommodation by Streets2Homes at the Oasis Hotel in Harlow. Nav Hussein, the hotel manager, checked on Hamid after receiving a concerned call over his whereabouts. When he went to his room, he saw two empty bottles of alcohol, and Hamid sitting upright on the bed. Hussein called out to him, but received no reply. He then noticed there was something different about the colour of Hamid’s hands and realised he was dead.

The autopsy revealed that Hamid had died of organ failure, but Protheroe is convinced he had simply lost the will to live. At the time, Hamid was on a complex cocktail of medication. “I think that it had got to the point where he’d just had enough, and he stopped taking his meds.”

A few weeks after his death, the council arranged a funeral for Hamid. Protheroe was disappointed by the turnout. He was pleased that Hamid’s family were there, but wondered where they had been when his friend needed them most.

Hamid Farahi Alamdari’s Facebook was last updated in November 2015. It states he started a new job as an aircraft engineer in 2006, and that he worked as an aircraft maintenance engineer for British Airways World Cargo. Most of his “friends” are beautiful young women from any number of countries, and a few are aviation engineers and fellow Iranians. His Facebook biography says he graduated from Bristol Aeronautical University in 1997. But there is no Bristol Aeronautical University. There is a renowned aerospace engineering department at Bristol University. However, Bristol University tells us Hamid never studied there. British Airways refuses to confirm that he worked there.

At the bottom of the list of friends is a man called Ariane F Alamdari. Ariane is Hamid’s nephew. Over the phone he tells us that his uncle could be a difficult man, particularly when he was drinking, but he did not believe he was a liar. “Of all his personality traits, embellishing the truth or telling fibs was not one of the things that I knew him for.” Ariane says the details of his uncle’s life are a puzzle to him. He introduces us to his father, Hamid’s older brother Saeed, who he says can tell us more.

Saeed is a 64-year-old academic who lectures in engineering at Bradford College and lives in Roundhay, a well-to-do suburb of Leeds. We meet in Roundhay Park, one of Europe’s largest city parks. Saeed is a short, slight man, who carries himself with an easy elegance. He has just completed the first half of his regular 10-mile walk around the lake. Saeed talks quietly and thoughtfully about Hamid and their parents, who came to Iran from Azerbaijan and spoke Turkish. He says that he was the lucky brother. Because he was eight years older than Hamid, he managed to leave Iran for the UK before the shah was overthrown and Ayatollah Khomeini established an Islamic republic in Iran. This was the main thing that set their lives apart, he says.

Saeed does not pretend to know every detail of his brother’s life. There were so many years they were apart. Like us, he has been trying to piece together a complex jigsaw since Hamid’s death.

Saeed Alamdari says it was was obvious from early on that his brother was outstandingly gifted. Photograph: Christopher Thomond/The Guardian

Saeed and Hamid were two of four children born into a middle-class family in Tehran. Their parents were practising Muslims and their children grew up in a secular Iran. Their father had a good, stable job working in security for the ministry of health, while their mother brought up the children. Saeed says it was obvious from early on that young Hamid was outstandingly gifted. “He was good at all sorts of sports, but most of all he was academically brilliant.” Both boys were drawn to the sciences, engineering and maths.

There was something else that stood out about young Hamid – he loved to take risks. “He and his friends used to go on to the roof of mosques and jump off them, and the curator would chase them,” recalls Saeed. “He liked getting chased. He wanted to be on the edge.”

Life changed for everybody after the revolution of 1979. By then Saeed had already established himself in the UK. He left Tehran in 1974, studied mechanical and aerospace engineering at Leeds University, did a masters degree in combustion and settled to a life in academia. Hamid was only 16 at the time of the revolution. In 1981, when he turned 19, he was conscripted into the army to fight in the Iran-Iraq war, which had begun the previous year. Because he was such a high achiever, he was drafted in as a lieutenant.

Saeed shows us a photo of a fresh-faced Hamid, standing at ease in an army uniform that looks a couple of sizes too big for him. However, Saeed thinks he was anything but at ease. Here was a young man responsible for the lives of so many other men who simply didn’t want to be there. “He had a platoon under his control, and most of these soldiers were drafted from villages. Hamid told me that on the day they were leaving for the front, the soldiers’ mothers got together and told him: ‘We’re leaving our sons in your hands.’ And during the war he lost most of his platoon – he always blamed himself for that.”

Saeed says the war left Hamid with post-traumatic stress disorder. Hamid suffered a recurring nightmare – that Iraqi soldiers were coming towards him with their hands raised, but he shot them anyway. After leaving the army, he went to India to study physics and to try to heal himself. Hamid told Saeed he studied for a degree, then completed a PhD. He also said he spent much of the time meditating and reading the great 13th-century Persian poets Rumi and Shams Tabrizi. “I think meditating and reading were coping mechanisms for him,” Saeed says. But by now Hamid also had another coping mechanism: booze.

After India, Hamid returned to Tehran, where he found himself in trouble. He could not cope with the oppressive regime or the alcohol ban. On one occasion, Hamid told Saeed, he and his friends were sentenced to 80 lashes after being caught drinking. “But one of his friends had a hump on his back, and Hamid said: ‘You’re not going to lash him.’ He was asked: ‘Well, do you want to take his punishment?’ He said: ‘I will’, and he received 160 lashes. That’s when he came to the conclusion that this was not the place for him.”

Tributes left on Hamid’s car following his death. Photograph: Adam Protheroe

In the mid-90s, Hamid came to the UK. He was in his early 30s and lived with his sister in Croydon while doing an admin job with the charity Age UK and studying English at Croydon College. According to Saeed, he won the college’s student of the year award. From there he moved to Bristol, but Saeed says that, rather than studying at university, as suggested on his Facebook profile, Hamid attended Bristol College to get a diploma to enable him to work on planes. It was around this time that he made his application to become Stephen Hawking’s assistant at the University of Cambridge. A letter dated 31 August 1997 confirms his application for the post, but there does not appear to be any correspondence about his shortlisting.

Hamid didn’t get the job as Hawking’s assistant, but was employed as an aeronautical engineer in Bristol. He had a stable job, lived with a girlfriend and made a decent life for himself. Saeed says these were his happiest years in Britain. But even then his brother had noticed a change. He had always been a risk-taker, but now he was becoming positively reckless. Hamid told him of a time he had gone to a drug-dealer’s house in Bristol to buy cannabis. “He said they had machetes and everything, and all the drugs were on the table. He and his friend took everything from the table and just ran away. For a few months he had to stay low. It’s not that he needed the money. He did it for the high.”

In 2008 Hamid lost his job, and went on a downward spiral. He moved to the market town of Great Dunmow in Essex and stayed with a friend for a while. By now it was obvious to Saeed that his brother was addicted to alcohol and cannabis and that his life was becoming increasingly chaotic.

At one point, Saeed paid for Hamid to go to Afghanistan for an interview for a job at a US air force base. Hamid also told Saeed that he went to Saudi Arabia to be interviewed for a post in avionics. But neither of these jobs materialised. Hamid would often phone Saeed at work, asking for money. Eventually, Saeed had to give an instruction not to put Hamid’s calls through to him.

Saeed had his own problems. He and his wife had separated and he was looking after his son, who has Asperger’s. When Hamid came to stay in Leeds, he inevitably brought trouble. There was one terrible weekend in 2011 when, within 20 minutes of Hamid arriving, there was a knock on Saeed’s door. It was Hamid’s drug dealer. “I was furious that he had arranged that. I told him, you come here whenever you want, Hamid, but no drugs. I’ve a son living with me – no drugs, no alcohol.” The next day they were walking back to Saeed’s car. “He had fallen behind me, and I realised he was drinking from a bottle of whisky in a brown paper bag. His face was getting redder and redder. When he saw me looking at him, he put it in his pocket. I dragged it out and smashed it on the floor. I said: ‘Didn’t I tell you, if you’re coming here, no alcohol.’ I had my son with me.”

Saeed couldn’t cope with his brother’s behaviour. “On the Monday, I took him to the bus station. I shook hands with him and I said: ‘I’ll see you in another world.’” That was the last time the brothers saw each other. Hamid would occasionally phone – usually asking for money. “The last time he phoned was three in the morning. His speech was slurred. I said to him: ‘Assume you have no brother.’” Saeed looks out on to the lake. He says he knows he was hard on Hamid, but he felt he had to choose between his brother and his son’s welfare. “I have my regrets,” he says. “Possibly I was asking too much from him.”

It was around five years later, in 2017, that Hamid sold his pension and ended up homeless. A year later he died. Hamid Farahi Alamdari – physicist, spiritualist, risk-taker, addict, war veteran. He may have fought his war in a faraway country for a remote regime, but in many ways he was typical of the thousands of British war veterans who are homeless – never shaking off the ghosts of the battlefield and left with lifelong PTSD. He might have told all the friends he made in that industrial park in Harlow about the beautiful and clever things in life, but ultimately it is his confessions about nightmares and the psychological scars left by war that left the strongest impression.

As for the PhD and being shortlisted for the job with Hawking, who knows? All his friends are certain of is that he had exceptional ability, that he died a disappointed man, and that they miss him. Adam Protheroe and Chrissy Sorce knew him for less than a year, but he changed their lives. Sorce says she knows she helped Hamid, but she still thinks she let him down at the end. “I felt a bit bad because he messaged me a few times and I was so busy with my own family that I didn’t really respond back to him as much as I should have. I did feel something towards him. He had a nice nature. I have a plant here he bought me for Christmas. I called it Hamid.” It’s a large succulent, is thriving and sits on her windowsill at home.

At the cafe in Harlow, Protheroe says he can’t drive past Tesco these days without thinking of his friend. He was “gutted” when he heard of Hamid’s death. He mentions a book Hamid gave him as a present. “It’s called The Prophet. It’s only a thin book, and it was just inspirational stuff – live your life this way, do good, be the best person you can.” It means a lot to him, he says.

Back in Leeds, Saeed admits it was a shock when he discovered Hamid had been living in a car and died homeless. He says he can’t express just how grateful he is to the people of Harlow for looking after Hamid when he had given up. “We were stunned by the number of books in the car, the clothes that people had given him, all the flowers at his funeral.” He spends a lot of time reflecting on his brother’s life, and says that these days he can remember the good times more easily. “Astrophysics was a favourite subject of his. Parallel universes.” He shakes his head. “It was a waste of a good life. I’m just hoping that in other universes, parallel universes, Hamid will be living a better life.”

Saeed and his sister decided not to tell their 90-year-old mother, who still lives in Iran, about Hamid’s death because they thought it would break her heart. “But about a week after he died, she called my sister from Iran saying: ‘I’m getting these dreams – either Hamid is ill or he is dead, which is it?’ And then my sister said: ‘Yes, he has passed away.’” Saeed says that his mother was relieved Hamid is finally at peace.

Saeed is getting ready for the second half of his walk around Roundhay Park. Sometimes he meets a man in the park who reminds him of his brother. “Seven o’clock in the morning he’s feeding swans, and he’s got a bottle of wine with him,” Saeed says. “There will come a time when I will strike a conversation with him. ‘Listen, I had a brother and he went right through what you’re going through now.’” For now, Saeed just tells him to take care of himself.

In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123 or by emailing jo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international suicide helplines can be found at befrienders.org

If you are worried about becoming homeless, contact the housing department of your local authority to fill in a homeless application. You can use the gov.uk website to find your local council

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to join the discussion, catch up on our best stories or sign up for our weekly newsletter