New South Wales courts could be flooded with tens of thousands of cases every year if the NSW government moves ahead with plans to roll out cameras that use artificial intelligence to detect drivers using their mobile phones, a parliamentary committee has warned.

The state parliament is considering legislation that would allow mobile phone detection cameras to be placed around NSW to capture drivers using their mobile phones while behind the wheel. The government estimates that there were at least 158 casualties on NSW roads between 2012 and 2018 involving mobile phones.

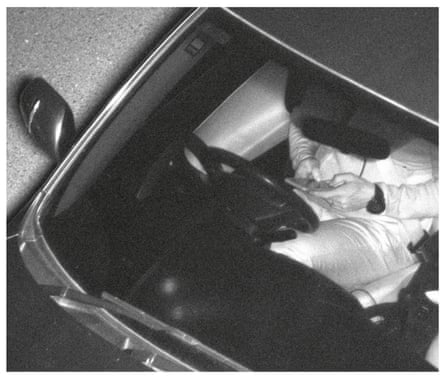

Under the plan, two cameras are used at each location, with one at an angle to capture people with phones to their ears, and a second placed to capture people using their phones in their laps.

Every car passing through thelocation is snapped, and Transport for NSW says it then deploys artificial intelligence to determine which drivers were using their mobiles. This involves pattern recognition – for example, drivers with both hands on the steering wheel are in the clear.

Those deemed not to have been using a device have their photos deleted within an hour, without any person having viewed the images, according to TfNSW.

Flagged images are cropped to show only the driver, then passed for review by a human. If the employee can’t tell whether a mobile is being used, the image is deleted within 48 hours.

A trial of the technology was conducted between January and June this year, in two fixed locations in metropolitan Sydney and in various other places, with the cameras being moved every four days.

In the fixed locations, 1.8% of all road users snapped were using their phones illegally, the executive director for road safety and maritime safety at TfNSW, Bernard Carlon, told the committee.

In the six months, TfNSW said, more than 8.5m cars were photographed, and more than 100,000 drivers were detected using their phones illegally.

But the committee, chaired by the Shooters, Fishers and Farmers party MP Robert Borsak, warned that the legislation to permit the cameras reversed the onus of proof from police to drivers, and would result in the local courts being tied up by cases.

When a police officer pulls over a driver for suspected phone use, the driver can choose to take the matter to court where they’re assumed innocent until proven guilty beyond reasonable doubt.

Under the proposed legislation, it is up to the driver to show, on the balance of probabilities, that the object in their hand is not a mobile phone.

The government hopes to snap 135m vehicles every year within four to five years of the program starting. If 1.8% of drivers are caught using their mobile phones, that adds up to some 2.4 million people. The committee said that if just 3% of their cases ended up in the courts, some 72,900 cases would be filed.

“A simple review of these numbers indicates that this program runs the risk of overwhelming the local court regardless of whether or not a reverse onus is in place,” the committee said. “Its effect on the driving population of New South Wales will also be significant.

“In these circumstances the impact of a reverse onus provision must be very carefully considered.”

The Law Society of NSW’s Michael Mantaj told the committee that the presumption that anything in the hand of a driver was a mobile phone was “divorced from reality”.

“It is likely to erode public confidence in the use of cameras as a means of enforcement of traffic law because it will feed into the already existing cynicism in some parts of the community that cameras, for example, speed cameras, are more about revenue raising than public safety,” he said.

“Lastly, it represents a dangerous precedent for future laws because it promotes an acceptance of the proposition that it is appropriate to create fundamentally unfair and fictional presumptions in order to make it easier to prosecute an offence.”

The NSW Council of Civil Liberties’ Stephen Blanks said there was no need to reverse the onus of proof if the quality of the photographs was high enough to rule out confusion about what was in a driver’s hand.

The NSW police assistant commissioner Michael Corboy said the reverse onus was about changing the culture to deter people being distracted on the roads.

“The reverse onus, which will say that if you are distracted in the car by using something that is a mobile phone or can distract you as a mobile phone does, to me is critical to the deterrence factor in relation to changing the culture of mobile phone use,” he said. “This is about deterrence.”

The committee supported the legislation but suggested that the Legislative Council consider amendments relating to the reverse onus of proof, the use of artificial intelligence and the legislation’s privacy implications.

The proposed system will cost $88m over the forward estimates, and modelling provided by TfNSW has estimated it could prevent more than 100 fatal and serious injury crashes over five years.